Review – Intel NUC DC53427HYE

I’ve been using a Lenovo X201 Tablet in a docking station as my main machine for about 3 years now. 8GB RAM hasn’t been enough for a while, which is why I got 16GB for my X230 laptop, and I’ve been having issues with the CPU running out of steam when using Skype and Google Hangouts.

I first came across Intel’s Next Unit of Computing (NUC) at Intel’s Developer Forum (IDF) in San Francisco in 2012. At the time I was a little dismissive of it in comparison to the Raspberry Pi for applications like streaming media, where it’s just too expensive (and larger than it needs to be). I did however feel that it would be a good basis for a small, quiet and frugal desktop machine.

Joe Baguley brought my attention to Alex Galbraith’s London VMUG presentation ‘Intel NUC Nanolab‘, which had me look at the NUC again. Alex also has a comparison table, and he concludes with the recommendation:

As regards this latest batch of models, I personally still think the sweet spot is with the Intel Core i5-3427U DC53427HYE 2nd Gen model, which includes vPro for remote access, and will turbo to a handsome 2.8GHz

Built in sound might have tipped me towards the newer i5-4250 model, but they’re not actually available, which is why I ended up getting an i5-3427 one (for £260 on eBay). The i5 version also had the gigabit ethernet and DisplayPort connectors that I wanted.

Making it complete

The NUC comes bare bones, so I popped in 16GB of RAM and a 480GB mSATA drive (both from Crucial). I moved a Windows 8 license over from an old Microserver, and jumped straight to 8.1 on install. A USB2 hub and a cheap USB sound adaptor from eBay finished things off (sadly my Dell 27″ monitor doesn’t seem to do sound over Displayport).

Installation

Windows 8.1 had no problem with drivers, and I got glorious 2560×1440 as soon as I plugged it in with DisplayPort. A visit to the Intel driver site got some more recent stuff for things like ACHI. Even the cheap USB sound card just worked :)

Performance

It’s subjectively very fast, though I might still be in the new machine honeymoon period. Sadly I can’t get Windows Experience Index numbers as WEI was ditched with the 8.1 release. Boot up speed is particularly good.

Less subjectively it clocks a Geekbench of 4815, which beats my same generation i5-3320M powered laptop at 4065[1].

Some noise

It’s quiet, but not quite silent. I would still notice the fan on the laptop, and I still notice the fan on the NUC. It’s nowhere near annoying or even distracting, but it’s there. I may have to splash out on the Akasa Newton V fanless case, which would also bring a couple of extra USB2 ports up front.

Update (13 Mar 2013): So I didn’t last very long. I ordered the silent case from CCL a few days after writing this, and I’ve been enjoying a silent working environment ever since.

Power peril

The NUC has received a bit of criticism for not having a mains cable for it’s power supply unit – it needs a C5 ‘cloverleaf’ (aka Mickey Mouse) lead. That wasn’t a problem, as it’s the sort of thing I do have lying around.

The peril comes from a lack of battery backup. Having used laptops for the last few years I’ve survived the all too frequent cuts and brownouts in my area, so it’s a rude shock to be back on the unreliable mains grid (especially when plumbers decide to do safety tests that trip my residual current detector – apparently it’s ‘too sensitive’).

I’m awaiting delivery of an IEC-C5 cable so I can run the NUC off my UPS.

Conclusion

I’m very happy with the NUC. It looks pretty on my desk, and offers up good performance without using loads of power and without making loads of noise. I may yet splash out on the silent case to get quiet PC nirvana. Apart from that I should be happy until I need something that can drive a 4K monitor (once they’ve sorted out all of the issues with driving those screens).

Note

[1] It’s a total mystery to me why a 35W CPU is beaten by a 17W CPU, but I’m left wishing that my laptop could use those watts better.

Filed under: review, technology | 3 Comments

Tags: benchmark, DC53427HYE, displayport, i5, i5-3427U, Intel, NUC, RAM, ssd

Review – Dell PowerEdge T110 II

It’s almost 3 years since I got my HP Microserver – time for a change. 8GB wasn’t enough RAM for all the VMs I want to run, and even with an unofficial upgrade to 16GB I was running out of room. The NL40 processor was starting to show some strain too. The time had come for something with 32GB RAM, which meant getting a real server.

Ridiculously cheap

I just missed out on getting my server for £219.95+VAT (£263.94). Procrastination got in the way, and when I did go to order they were out of stock. They’re now back at ServersPlus for £249.95+VAT (£299.94) – and that’s the version with a proper server CPU (a Xeon E3-1220 v2) rather than some weedy Pentium or i3 meant for a regular desktop.

I know it’s possible to get PCs for even less than £300 these days, but a proper server from a brand name vendor that’s nicely put together seems like a bargain[1].

Fill her up

A server with 4GB RAM and a 500GB hard disk is approximately useless[2]. I had a couple of 3TB spindles to transplant, a freshly shucked 4TB drive that cost me £124.99[3] and ordered 32GB RAM (£307.18) from Crucial and a 240GB Transcend SSD that was on sale from eBuyer for £99.99. My server was no longer ridiculously cheap, but for less than £1000 I had a machine that would be fast and have lots of everything.

Performance

Given a choice it would have been nice to pay a small premium for the E3-1230 v2, which with a CPU Mark score of 8890 seems much faster than the 6503 of E3-1220 v2 – a difference that just doesn’t make sense on paper for a 0.2GHz clock speed differential (and no other notable differences in cache etc.).

Running Geekbench turned in a multi-core score of 8573 – the new house champion by a good margin – just what I hoped for with a full fat CPU in a big box.

Subjective performance is great, even when running a load of VMs. The only let down is DivX Converter transcoding, which seems to thrash the CPUs without going very much faster than it did on the HP Microserver.

Network transfer rates are substantially better than I was seeing with the HP Microserver (Iperf is clocking around 400Mbps over a less than perfect 30m cable run – I was previously seeing 150Mbps).

Build

The case is solid but not too heavy. Opening is achieved with a simple single latch, and everything is very tidy inside.

It comes with 4 slide in 3.5″ disk trays, which are great (and often a premium item for other brand servers). Using a 2.5″ SSD on an Intel mounting plate made cable routing a slight stretch, but otherwise it’s a very neat arrangement. There’s a 5th SATA port internally, which I guess is there for an optical drive, but I’ve routed it to a removable HDD caddy. There’s also an eSATA port (but no eSATA power).

There are 2 USB2 ports on the front, 4 around the back and another couple on the motherboard. There’s also gigabit ethernet, VGA, and a proper old 9 pin serial port[4].

The server is quiet in operation, and seems to run nice and cool. The power supply is rated at 305W, but I’d guess it’s not slurping anything like that – fingers crossed that my electricity bill doesn’t leap up now that I’ve given up on the Microserver.

Conclusion

The new server has given me the processing power, storage and VM space that I need now, with a good deal of headroom for future needs. At less than £1000 for such a high spec I’m very happy, particularly given the strong performance and good build quality.

Notes

[1] I’m left wondering why these don’t get bought as the basis for cheap workstations?

[2] A 4/500GB configuration might just about do for a basic office server these days, but I wish it was possible to buy (on Dell’s web site) a minimal config with no RAM/disk.

[3] Supply chain insanity (and varying warranty offerings) mean it’s cheaper to get external disks and remove the disk from its shell than it is to just but the disk naked.

[4] I thought that this might be useful for my old APC UPS until I discovered that serial UPS support disappeared in Windows 2008.

Filed under: review, technology | 8 Comments

Tags: benchmark, build, Dell, E3-1220, E3-1220v2, performance, RAM, review, ssd, T110, T110 II, VMs

Multi tier apps in Docker.io

Docker provides the means to link containers, which comes in two parts:

- Outside the container (on the docker command line) a ‘-link name:ref’ is used to create a link to a named container.

- Inside the container environment variables REF_… are populated with IP addresses and ports.

Having linked containers together it’s then necessary to have a little plumbing inside the containers to get the contents of those environment variables to the right place.

My example application

A while ago a saw a demo of Apcera, which used a little ToDo list application as a means to show off the capabilities of the platform. I thought a similar demo would be useful for CohesiveFT’s VNS3[1], and I found a suitable basis with theponti‘s sinatra-ToDoMVC app. My version of the app has been modified to use MySQL as a back end, and I also add Nginx as a front end to make a 3 tier demo.

If you want to just dive in

I’ve put my app into github, and it’s available as a trusted build from my page on the Docker public index. To just run it up start each tier in turn:

# first create the directory for persistent data: sudo mkdir -p /data/mysql # start the database sudo docker run -d -p 3306:3306 -name todomvc_db \ -v /data/mysql:/var/lib/mysql cpswan/todomvc.mysql # start the app server sudo docker run -d -p 4567:4567 -name todomvc_app \ -link todomvc_db:db cpswan/todomvc.sinatra # start the web server sudo docker run -d -p 443:443 -name todomvc_ssl \ -link todomvc_app:app cpswan/todomvc.ssl

The database

The MySQL database is the base dependency, so nothing happening here in terms of linking. I’ve adapted Ben Schwartz’s scripts for creating a MySQL Docker container to add in the creation of the ToDoMVC database.

The only other noteworthy thing happening here is the externalisation of the MySQL database storage back to the host machine using the -v flag.

The app server

This is linked back to the database with ‘-link todomvc_db:db’. Inside the container this gives various environment variables starting DB_. The appropriate one is parsed into the database URL within the Sinatra application using the following couple of lines of Ruby:

dburl = 'mysql://root:pa55Word@' + ENV['DB_PORT_3306_TCP_ADDR'] + '/todomvc' DataMapper.setup(:default, dburl)

Note that the Dockerfile for the app server is grabbing the Ruby code straight from the docker branch of my fork of the sinatra-ToDoMVC application. If you want to see that database URL in context then take a look at the source for app.rb. The credentials being used here are what was set back in the database start script.

The web server

This is linked back to the app server with ‘-link todomvc_app:app’. Inside the container this gives various environment variables starting APP_. As Nginx can’t do anything useful with those variables it’s necessary to parse them into nginx.conf before starting the server, which is what the start_nginx.sh script is there to do:

#!/bin/bash cd /etc/nginx cp nginx.conf.template nginx.conf eval "echo \"`cat upstream.template`\"" >> nginx.conf service nginx start

The nginx.conf has been split into two templates. For the bulk of it (nginx.conf.template) there’s no need to environment substitution, in fact doing so will strip out env variables that need to be there. Only the upstream section is required so that:

upstream appserver {

server $APP_PORT_4567_TCP_ADDR:$APP_PORT_4567_TCP_PORT;

}

}

Gets turned into something like:

upstream appserver {

server 172.17.0.62:4567;

}

}

The trailing brace is there to complete the unfinished http section from the main nginx.conf.template.

That’s it :)

Browsing to https://docker_host/todos should get the todo list up.

Note

[1] For my demo with VNS3 I spread the tiers of the app across multiple clouds – almost the exact opposite of what’s happening here with all three tiers on the same host. In that case VNS3 provides the linking mechanism via a cloud overlay network – so there’s no need to tinker with the application config to make it aware of it’s environment – hard coded IPs are fine (even if they’re generally a config antipattern).

Filed under: code, Docker, howto | 3 Comments

Tags: address, app server, database, Docker, Docker.io, Dockerfile, enviornment, link, linking, MySQL, Nginx, port, Ruby, Sinatra, SSL, ToDoMVC, web server

Ubuntu images on Docker.io

When trying to install node.js into the default official Ubuntu image on Docker the other day I hit a dependency issue. Node.js needs rlwrap[1], and rlwrap is in the universe repository, which it turns out isn’t part of /etc/apt/sources.list for the 12.04 image:

deb http://archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu precise main

Things worked using the ubuntu:quantal (== ununtu:12.10) image because that has an expanded sources.list that includes universe and multiverse – a much larger selection of available packages:

deb http://archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu quantal main universe multiverse

It’s a total mystery to me why that difference should be there.

This specific issue can be fixed with a one line addition to the Dockerfile that adds the universe repository[2]:

RUN sed -i s/main/'main universe'/ /etc/apt/sources.list

I took a look at the stackbrew/ubuntu images, which it turns out have a much more complete and consistent set of sources.list (for all 4 versions that are presently available: 12.04, 12.10, 13.04 and 13.10):

deb http://archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu version main universe deb http://archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu version-updates main universe deb http://archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu version-security main universe

Unfortunately this causes bad things to happen if you run ‘apt-get update && apt-get upgrade -y’:

dpkg: dependency problems prevent configuration of initramfs-tools: initramfs-tools depends on udev (>= 147~-5); however: Package udev is not configured yet. dpkg: error processing initramfs-tools (--configure): dependency problems - leaving unconfigured

There’s really no need for initramfs stuff within a container – so the broader sources.list is causing the container to attempt to do unnatural things.

Conclusion

Dependency management in the current crop of Ubuntu images at hand for Docker.io is a bit of a mess at the moment. It’s not hard to straighten things out, but things that superficially look like they’re doing the right thing can come with unintended consequences that don’t fit well with the containerised approach.

Notes

[1] Here’s the error message:

Some packages could not be installed. This may mean that you have requested an impossible situation or if you are using the unstable distribution that some required packages have not yet been created or been moved out of Incoming. The following information may help to resolve the situation: The following packages have unmet dependencies: nodejs : Depends: rlwrap but it is not installable

[2] Make sure there’s an ‘apt-get update’ afterwards

Filed under: Docker | Leave a Comment

Tags: 12.04, 12.10, Docker, Docker.io, Dockerfile, main, node, node.js, precise, quantal, rlwrap, sed, sources.list, Ubuntu, universe

Node-RED on Docker

Docker is going into the next release of CohesiveFT’s VNS3 cloud networking appliance as a substrate for application network services such as proxy, reverse proxy, load balancing, content caching and intrusion detection. I’ve been spending some time getting familiar with how Docker does things.

Since I’ve also been spending some time on Node-RED recently I thought I’d bring the two activities together as a demo application.

Following in the footsteps of the SSH example I was able to use Oskar Hane’s guide to creating a Node.js Docker.io image and then add in Node-RED[1]. This gave me something that I could run, but not something that was particularly repeatable or malleable.

Having read through Troy Howard’s excellent Where are my Docker images stored? I then set about encoding the steps I’d followed into a Dockerfile:

FROM ubuntu:quantal RUN apt-get update RUN apt-get upgrade -y RUN apt-get install python-software-properties python g++ make -y RUN apt-get install software-properties-common wget unzip -y RUN add-apt-repository ppa:chris-lea/node.js -y RUN apt-get update RUN apt-get install nodejs -y RUN wget https://github.com/node-red/node-red/archive/0.5.0.zip RUN unzip 0.5.0.zip -d /opt RUN cd /opt/node-red-0.5.0 && npm install --production RUN rm 0.5.0.zip

I broke my normal habit of only using Ubuntu LTS builds here as for some peculiar reason rlwrap, which is needed for Node.js, doesn’t seem to install properly on the Ubuntu 12.04 Docker image.

The nice thing about the way the Dockerfile works is that when things break you don’t have to repeat the preceding steps. Docker just uses its image cache. This makes testing much less painful than in other environments as the cost of making mistakes becomes pretty minimal. This is the key to the power of Docker, and particularly the Dockerfile – the incremental friction between hacking away at the command line and developing a DevOps script has become tiny. It really makes it easy to create something that’s repeatable rather than something that’s disposable.

I also found out that context isn’t preserved from one run command to the next, which is why lines 11 and 12 are like that rather than a more (interactively) natural:

cd /opt unzip ../0.5.0.zip cd node-red-0.5.0 npm install --production

Once the Dockerfile built correctly with:

sudo docker build -t cpswan/node-red-0.5.0 .

I could then launch an instance with:

sudo docker run -d -p 1880:1880 cpswan/node-red-0.5.0 \ /usr/bin/node /opt/node-red-0.5.0/red.js

and bring it up in my browser by navigating to http://host_ip:1880

I’ve uploaded the resulting image cpswan/node-red-0.5.0 to the public index if you just want to run it rather than making it.

Note

[1] Perhaps this wasn’t the Docker way to do things. Searching the Docker public image repository turns up an image christened ‘dun‘ Docker, Ubuntu, Node (though it is a few point releases behind on node.js).

Filed under: code, CohesiveFT, Docker | 2 Comments

Tags: Docker, Docker.io, Dockerfile, image, index, node, Node-RED, node.js, repository

OpenWRT on TP-Link TL-WR2543ND

If you want to dive straight into install instructions then head over to the TP-Link TL-WR2543ND article on the OpenWRT Wiki.

Why?

When my son smashed the screen on my iPad 2 I think he also damaged the WiFi antenna. I had to be just about be sitting on top of a 2.4Ghz hotspot to get any 802.11g/n signal. 5GHz seemed OK though, so rather than getting the iPad repaired again I thought it would be easier/cheaper to get an access point that supported 802.11a.

I didn’t really want a router, but standalone dual band access points don’t seem to be a thing, so I went for the TL-WR2543ND as it was pretty cheap on Amazon (£40.77 when I got it, now £37.99 on Amazon.co.uk [1]).

When the router arrived it was a bit of a disappointment. Firstly I thought that dual band would mean both bands at once (it doesn’t), and secondly there was no obvious way to get it working nicely on my usual home network subnet. I had to treat the home network as the WAN, and then have another subnet for devices connected to the router.

Having done some other upgrades to the home network I wanted a 5 port gigabit switch in the lounge, and it would be handy to have the 5Ghz access point there too. I just needed some way to liberate the WAN port on the router, and there was no way to do that with stock firmware.

OpenWRT

OpenWRT is an open source firmware platform for routers. I’ve previously used in on an older TP-Link device that I had in the lounge, and installation onto the TL-WR2543ND was a breeze.

Using the web interface from a laptop connected to one of the wired LAN ports I ran through initial configuration:

- Enabled SSH, disabled password login and installed a key

- Set up WiFi

- Removed dnsmasq to avoid clashes with the DHCP/DNS elsewhere on the network

- Gave the LAN interface a static IP on my usual subnet

Almost there…

I now had a router with a 4 port switch and 5GHz WiFi, but I needed that extra port. At this point I tried bridging the LAN (eth0.1) and WAN (eth0.2) interfaces. I thought I had it working (stuff plugged into the WAN port was pingable from elsewhere on the network), but on power cycling no traffic passed on the switch, and I couldn’t connect to the web or SSH interfaces.

Disaster :(

Recovery

Now the stuff about serial port recovery from the install instructions came into its own. I’d stupidly locked myself out of the device, and I needed a way back in. Luckily it was pretty easy to solder a few header pins into the right place, and the FTDI adaptor that I got for my Nanode let me connect a serial terminal. I was back into the Linux shell[2], and a bit of hacking at /etc/config/network to remove the bridge had me back in over the network.

What actually worked

Having got myself back in (and made a backup of a working network config in case I messed it up again) I tried unsuccessfully to make bridging work. Even when I managed to do this in a way that didn’t lock me out of the router it seemed to cause ARP floods. I was doing the software equivalent of plugging a cable into two ports of the same device.

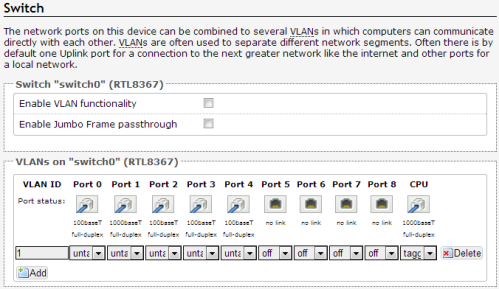

The correct approach was to disable VLAN functionality in the Network->Switch menu (I also deleted VLAN 2 and set port 0 to untagged on VLAN 1).

This does the trick because the WAN port is/was just a different VLAN on the same switch as the LAN ports, so if I want them all to work together then naturally I just treat them as part of the same VLAN (by not having any distinct VLANs at all).

Conclusion

I’ve now got what I want – a 5 port switch with attached 5GHz access point, rather than what I bought – a dual band WiFi router. Less is more.

Notes:

[1] I was going to put in an Amazon.com link for US readers, but it seems to have been discontinued.

[2] There was no need to reinstall the firmware

Filed under: howto, technology | 2 Comments

Tags: 2.4GHz, 5GHz, 802.11a, firmware, gigabit, OpenWRT, router, serial, switch, TL-WR2543ND, TP-Link

Pi Lite with Node-RED

This was trivially easy, but it’s a nice example of how simple integration is now becoming due to the strength of various open source communities.

Pi-LITE

The Pi Lite is an array of lots of LEDs (126 in a 9×14 matrix to be exact). I bought a pair of them during the initial Kickstarter campaign. It has its own micro controller, and is accessed via a serial port[1], which means it’s pretty easy to get messages onto it from most languages and frameworks.

Node-RED

Node-RED is a visual integration tool that runs on node.js. It’s very easy to get it going on a Pi using Raspbian:

# First install node.js wget http://node-arm.herokuapp.com/node_latest_armhf.deb sudo dpkg -i node_latest_armhf.deb # Make sure we have git sudo apt-get install -y git-core # Install Node-RED git clone https://github.com/node-red/node-red.git cd node-red npm install --production # Install serialport package npm install serialport #Start Node-RED node red.js

Once up and running browse to http://pi_ip:1880 and wire together a ‘Hello World’ example with an inject input (with a Paylod of ‘Hello World’) and a serial output (configured for /dev/ttyAMA0 at 9600 baud):

Now clicking on the button on the Hello World injector results in Hello World scrolling across the Pi Lite in large friendly letters :)

Once that’s running then it’s easy to substitute messages coming from tweets, MQTT queues or whatever else and feed them onto the matrix.

Note

[1] Since the GPIO serial port is normally set up for logging and console access it’s necessary to do some reconfiguration before using the Pi Lite.

Filed under: Raspberry Pi | 1 Comment

Tags: node, Node-RED, node.js, PI, Pi-Lite, Raspberry Pi, raspbian, RPi, serial, serialport, ttyAMA0

Chromebook sales have been a big deal over the past year. This of course leads to the naysayers asking why they aren’t showing up in web logs everywhere? I think the answer is pretty straightforward… Chromebook users are likely much the same as cheap tablet users – so they’ll be mostly using them for gmail, Facebook and other very mainstream sites (that don’t tend to share their traffic data). Of course there will be a bit of casual off piste surfing , but that’s mostly showing up in the noise of the long tail.

The folk speculating about this should look in the mirror. Not literally. Macs are a tiny proportion of notebook sales, but account for a decent amount of web traffic . Conclusion: Mac users surf more than others. It’s a similarly skewed story for the iPad in the tablet world – it’s share of units sold is diminishing, but it’s share of the web remains very strong.

There are some consequences here – a mass audience that just isn’t showing up in many places, and a niche (more affluent) audience that gets around more. So the Google and Facebook engineers need to think about the Chromebook masses, but not (yet) so much everybody else.

For what it’s worth the Samsung ARM Chromebook I bought a year ago has got incrementally better over the past 12 months. With the SSH and RDP niggles gone it now does pretty much everything that I expected of it. It doesn’t get a ton of use since I picked up my Lenovo X230, but it’s the machine I reach for when I’m still in bed and need something with a keyboard.

Filed under: technology | Leave a Comment

Tags: Chromebook

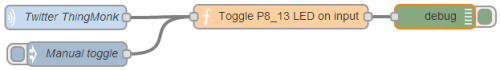

I spent yesterday at the excellent ThingMonk hack day. Whilst everybody else was playing with Arduinos, Node and Johnny5 I decided to have a play with Node-RED on the BeagleBone Black I’d brought along. The eventual outcome was something that turned an LED on or off every time somebody tweeted ‘Thingmonk’. Our host James Governor tried to tweet a picture of it (which got stuck on his phone).

The flow started with a Twitter parser connected to a MQQT topic running on RabbitMQ running on my next door neighbour’s laptop (thanks Mark). I then had Node-RED subscribed to the topic on Mark’s broker feeding into a function to toggle an LED attached to the P8_13 GPIO pin on the board.

It all looks pretty simple now, but I had some fun getting going.

It all looks pretty simple now, but I had some fun getting going.

Getting online

I’d brought the BeagleBone with me because I could get it up and running with a single USB cable attached to my laptop. In order to get stuff installed on it I had to share my laptop WiFi with the BeagleBone network connection, turn off my firewalls, and make a few incantations on the BeagleBone:

route add default gw 192.168.7.1 echo 'nameserver 8.8.8.8' >> /etc/resolv.conf

It’s also a good idea to make sure that the date and time are correct:

ntpdate pool.ntp.org

Node-RED

The project has specific instructions for the BeagleBone Black, but that’s not the complete story. I had to refer back to the installation guide, because I’d missed the crucial step of:

cd node-red npm install --production

I also edited settings.js to enable bonescript by commenting out one line and uncommenting another:

//functionGlobalContext: { }

functionGlobalContext: { bonescript:require('bonescript') }

//functionGlobalContext: { arduino:require('duino') }

}

I could then start it up with:

node red.js

Here’s the code that flips the LED when a tweet is received[1]:

var pin = "P8_13" var b = context.global.bonescript; context.state = context.state || b.LOW; b.pinMode(pin, b.OUTPUT); (context.state == b.LOW) ? context.state = b.HIGH : context.state = b.LOW; b.digitalWrite(pin, context.state); return msg;

Mosquitto

Everything was fine with Mark’s MQTT until the power cut. No WiFi meant no connectivity to his laptop. I decided to install my own MQTT broker… Mosquitto is packaged for Debian (and Ubuntu), so if I was running that it would be simple to install, but I was running Angstrom to get bonescript etc. to go with Node-RED. So I had to install Mosquitto from source[2]:

opkg install python-pip tcp-wrappers \ python-dev python-setuptools coreutils \ libxslt libxslt-dev packagegroup-core-buildessential wget http://mosquitto.org/files/source/mosquitto-1.2.3.tar.gz tar -xvf mosquitto-1.2.3.tar.gz cd mosquitto-1.2.3 make make install cp /etc/mosquitto/mosquitto.conf.example /etc/mosquitto/mosquitto.conf adduser mosquitto

You’ll probably want to visit the Mosquitto downloads page to make sure you’re getting the latest version (it was 1.2.2 when I did this yesterday).

Notes

[1] Node-RED has a Twitter input element that I could have used, but I couldn’t get authentication to work (and spent no time trying to fix it), and part of the fun of a hack day is joining projects together.

[2] Thanks to Bruce Holmes for pointing me in the right direction here. It looks like pkggroup-core-buildessential became packagegroup-core-buildessential at some stage.

Filed under: BeagleBone | 9 Comments

Tags: Angstrom, BeagleBone Black, Mosquitto, MQTT, Node-RED, node.js

Bitcoin – the Satoshi limit

The smallest presently supported subdivision of a bitcoin is 0.00000001, known as a Satoshi. This unit could also be called 0.01 µBTC or 10 nBTC (if there was such a thing as nano Bitcoin[1]).

The Satoshi limit[2] happens when the smallest unit of Bitcoin equals the smallest unit of currency that we’re happy to use for everyday transactions. This reasonably falls in the range of 1¢ to $1.

So what happens if a Satoshi is worth 5¢ (a log midrange value for the reasonable range)?

A 5¢ Satoshi implies that all 21 million BTC would have a total value of 5¢ * 21000000 / 0.00000001 = $105 Trillion. At that valuation a single BTC would be worth $5m

$105T is in the same order of magnitude as all world total liquid assets, and an order of magnitude more than all of the gold ever mined (which has been used by one analyst already as a model for Bitcoin value).

It looks like whoever designed this ‘weapon which exploits greed and social engineering to astonishing effect‘ got their sums right.

Notes

[1] There’s no reason why the Bitcoin protocol couldn’t be subsequently modified to deal with smaller subdivisions, but the Satoshi is what we have for the time being.

[2] I have my brother to thank for this observation.

Filed under: Bitcoin | Leave a Comment

Tags: Bitcoin, BTC, Satoshi, value