Winners and losers

TL;DR

Standardised tests like A Levels will inevitably have winners and losers, and in normal circumstances those people will usually know why they won or lost. For the losers it’s likely that they experienced some bad luck; but the key point here is that experience – they know why things didn’t work out. When that experience of bad luck gets replaced by an algorithm handing out bad luck outcomes it’s easy to see how a sense of injustice quickly builds; as the connection between experience and outcome has been severed.

Background

This is a post about the unfolding high school ‘exam’ fiasco in the UK, where 18-year-olds are getting their A Levels that are the gateway to University, and 16-year-olds are about to get their GCSEs.

In any process like this there are inevitably winners and losers…

In an ordinary year

Winners:

- The kid who went through just the right past papers, so the exam hits the stuff they prepared for

- The kid who slacked off all the way through, but pulled it out of the bag in a final push for the exams

Losers:

- The kid who was upset because their dog died that morning

- The kid who got ill

- The kid who worked hard all year, but somehow fluffed it on the day

2020 was going to be different

With exams cancelled because of corona virus there were always going to be different winners and losers, because supposedly kids were going to be assessed based on evidence they’d been able to provide through to March:

Winners:

- Kids that worked hard all the way through

- Kids who dodged that bad exam day

Losers:

- Kids who slacked off all the way through, but planned on pulling it out of the bag in a final push for the exams

But not like that

It seems that the government decided it would be far too much trouble to look at evidence for individuals (even as a means of refining their model)[1], which leads to different winners and losers:

Winners:

- Kids who go to schools that have previously done well (especially private schools[2])

Losers:

- Outstanding kids going to historically poorly performing schools.

Even ignoring any work done over the past 2 years, the latter point could have been re-calibrated for by paying some attention to past GCSE results. The kid who got 9 A*s at a school that never previously had anybody getting any A*s is exactly the sort of outlier that data scientists live for[3].

The bad luck lottery

As noted above, in an ordinary year there will be a bunch of kids who are unlucky. Something happens on the vital day/week/month that makes them unable to meet their own expectations.

But to keep 2020 the same as 2017-2019[4] means handing out bad luck by algorithm, and that leads to an experiential gap that comes with a massive sense of discrimination.

If your dog died, or you got ill, or you fluffed it on the day then you know about that – it happened to you. There’s a correlation between lived experience and outcome.

But there were no exams, which means there can’t be any bad luck on exam day, which in turn means that a giant dollop of bad luck has been handed out to kids where there’s no correlation between lived experience and outcome. They just feel shafted, because they have been.

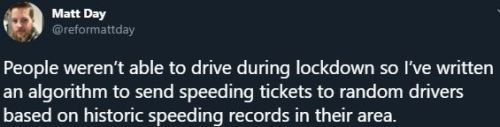

Matt Day perfectly sums up how ridiculous it would be for us to hand out bad luck in other aspects of life to keep the statistics in line:

Joining the fight

I just chipped in to the Good Law Project ‘Justice for A Level Students‘ campaign, and there’s also a campaign for Grading Algorithm: Judicial Review from Foxglove.

Conclusion

Any standardised testing process will have winners and losers, and we’re used to situations where bad luck leads to bad outcomes. I don’t think anybody’s comfortable with those same bad outcomes being handed out by algorithm, especially when it seems that the algorithm has been designed to preserve historic inequality.

Notes

[1] The BBC’s ‘Why did the A-level algorithm say no?‘ provides a good overview, and I’ve collected some more on the combo of ‘education’ and ‘algorithm’ PinBoard tags.

[2] I’m not writing this to ding private schools – they’re an ongoing part of structural inequality that I’ve willingly participated in myself, and for my own kids.

[3] Though it seems that Ofqual scared off the good statisticians and data scientists with NDAs that seem like the prequel to a cover up.

[4] The best description I’ve read of what happened is that grades were handed out to ‘ghosts of past students‘ rather than paying any attention to the 2020 individuals.

Filed under: wibble | 1 Comment

Tags: A-Level, algorithm, exams, GCSE, losers, luck, Ofqual, testing, winners

Any large enough group of numbers can produce a statistically pleasing result even if every single data point is individually incorrect. (With apologies to the CLT)

False accuracy was the wrong approach here.