No more Mr Nice Guy

and no more Mr Shy Guy.

I’m now out from under a big corporate blogging policy, which means that I don’t have to worry about upsetting any individual or corporate entity on the planet by saying bad things about them or their products (or indeed good things about their competition).

Disclaimer – this is still my personal blog, and does not represent the views of my new employer.

In case any of you were wondering…

The digital SLR that I bought shortly after posting on the topic was an Olympus E-510 (dual zoom kit). It seemed like the best compromise on price/performance at the time, and I also liked the look of the 25mm pancake lens after reading such good things from Tim Bray about the Pentax versions. I ended up kicking myself when the Nikon D700 came out a few months later, as it was pretty much exactly what I wanted. Maybe a bit too heavy, and a bit too pricey, but close enough. I’m still waiting for those full frame sensors to come down the market onto bodies with reasonable cost and weight. Something equivalent to my old Canon A1 would be perfect.

My netbook is a Lenovo s10e. I see that there’s an s10-2 out now, which is supposed to have the option of integrated 3G WWAN. Hopefully I won’t have to wait too long for it to come to the UK (and hopefully it won’t be locked to some dreadful netbook with 3G package that’s only available from a mobile telco).

Filed under: this blog | 1 Comment

The right not to get caught

For @monadic, who forgot this was happening, and @stephenbonner who asked for a blog post summarising events – a short write up of last Friday’s Open Rights Group event, ‘resisting the all seeing eye’, featuring Cory Doctorow and Charles Stross.

Things got off to a fairly predictable start for anybody who follows Cory’s and Charlie’s blogs and other postings. I’ve not got around to reading Little Brother yet, but that seems to be where Cory’s head still is. Charlie has been immersing himself in the next part of his Merchant Princes series, so it was no surprise to hear him making references to historical architecture and social norms. This was perhaps one of the key take away points of the evening – the contemporary concept of privacy hasn’t been around that long, being mostly a middle class 20th century contrivance, so should we be really all that shocked/bothered that the concept is being changed as new social norms emerge?

As the introductions wound up Cory touched upon the futility (and obnoxiousness) of web filtering, particularly in schools. This resounds for me also in the enterprise context; on the one hand filtering seems to have gotten more and more in the way of doing business, but on the other hand it is becoming increasingly futile as people bring to work WWAN connected netbooks and phones. There were two choice examples of kids hacking around filtering; 1) they would search for ‘proxy’ and then jump to page 75 of the results – no network administrator would bother to go to page 75, 2) kids would pick a random blog with an open comments system and use that for chat. Cory said that we should do more to teach kids about this stuff, then Charlie said we should do more to teach politicians about this stuff, and then the audience participation started…

One of the more interesting questions was whether we would see ‘the end of hypocracy’ – that openness in all areas of life, including politics, would prevent politicians (and government) from behaving badly. Cory gave some examples of why this doesn’t appear to be working, citing 1) the home secretary choosing to upgrade cannabis despite her own confession to using it and advice from the government chief scientist and 2) his own recent writing on how transparency means nothing without justice. For me this raised interesting questions about how justice can be returned to society, and whether society’s expectations around politicians are reasonable? A follow on point was made that it would become increasingly hard to enter politics with a clean sheet, and that this might encourage political dynasties where kids are brought up to enter office, isolated from real life and experience. Along with politics becoming a career (entered in some way directly from higher education) rather than a calling (entered later on in life having gained experience elsewhere) – this could clearly be a problem. What does it take for the public to accept that politicians have some dirty laundry too?

Clearly there was an expectation in the room that issues around privacy should be somewhere on the political agenda. The question I never got around to asking was ‘what will it take for these issues to find their way onto a mainstream manifesto?’. Robin Wilton recently observed some accidental alignment between opposition party proposals and the pro privacy lobby; but here I’m tempted to invoke the corollary to ‘never blame on malice that which can be explained by incompetence’, which is ‘never ascribe to competence that which can be explained by good luck’. Getting back to the points on education, the underlying problem here is that nobody understands this except the geeks, and so nobody cares except the geeks – that’s just not enough votes.

Both Cory and Charlie were quite down on the tabloid press, ‘the red tops’, and their role in steering public opinion, particularly the link between profit and fear mongering. This was linked back to politicians being trapped in a vice over things like terrorist threat warnings – nothing can ever be relaxed or reversed, as then blame can be ascribed. To avoid blame do nothing. On the way home I read Bob Blakley’s piece where he comes up with ‘Blakley’s Law‘, to describe what’s going on here (with specific reference to the porkalypse) – “Every public alert system’s status indicator rises until it reaches its disaster imminent setting and remains at that setting until it is retired from service.”. I know from my time in the military that it’s impossible to maintain states of high alert for more than a few days, and even raised awareness becomes tired in a matter of weeks. It is just ridiculous that we still hear announcements all the time along the lines of ‘in these times of heightened alert (following 9/11, which happened over 7 years ago) blah blah blah’. Of course those announcements are just another part of the state sponsored apparatus of fear/control, in which the press are complicit in playing along rather than calling them out. At least we have Craig Murray.

Aggregation of personal data was a recurrent theme. Clearly the problem isn’t that people surrender nuggets of personal information for specific time bound purposes, but that those nuggets end up sitting around in perpetuity on (public) databases where they can be aggregated and mined (for purposes that may be against the individuals wishes or best interests). Charlie suggested that it would be nice to have a system where data is accessible when it’s less than 2 years old (whilst still current) and more than 100 years old (when the individual is likely dead, but the historians might care). One of the audience pointed out that this sounded like an elaborate DRM scheme, which got Cory going on about the real evils of DRM being in hardware that is outside the control of the user/owner – well dodged that man – you should be in politics ;-) When asked about pratical measures both Cory and Charlie talked a lot about browsers, a little about CCTV, and a bit about RFID.

The next really interesting area for debate was privacy around DNA, and Charlie picked up the batton pointing out that full genome sequencing is getting cheap very quickly. He then went on to explore ‘shotgun sequencing’ that’s going on for ocean samples, and could also be applied to crime scenes. The trip into the future ended with a hypothetical toothbrush that could identity infections before they became symptomatic. Clealy this could have tremendous benefit for public (and individual) health; and also disasterous consequences for health insurance premiums etc. It’s here that we get to the heart of the issue – privacy in this context is about not wanting to surrender or have used against me information that might make me worse off – like that I committed a crime (e.g. speeding) or have genes that might make me a higher risk. Yet at the same time I don’t want speeding motorists to run down my kids, or pay for high risk customers to be using the same life insurance company as me. I want technology to make my life safer and less costly, I don’t want technology to make my life subject to state interference and more expensive – two sides of the same coin.

This brings us to some of the closing points… there is a social contract that exists between us as individuals, between us and commercial entities, and between us and the state. Technology is causing changes to that social contract – changes that we hope will benefit more than they harm. As we look to younger generations, they are being indoctrinated into accepting some of those changes, but often without open and fair debate about what the alternatives might be. Policy shapes the social contract, and the social contract shapes policy; but participants in both policy formulation and engagement in the broader social contract need to be informed of the issues.

Endnote – On the way home I fired an email to Charlie pointing him to Jerry Fishenden’s work in this area. The weekend also brought us a great post from Ben Laurie on the relationship between privacy and social networks.

Filed under: wibble | 9 Comments

Tags: Charles Stross, Cory Doctorow, hacking, open rights group, politics, privacy, transparency

Netbooks are small, not crippled

I’ve posted already about my netbook, and I’m sure made it very clear that I like it. Suggestions that people will give up their netbooks for ‘real’ machines once there is some kind of economic recovery are in my opinion ridiculous. I didn’t buy my netbook because it was cheap (though I’m pleased that it was). I bought it because it has sufficient compute power for all of the applications that I’d like to run on the move, and it has the weight, durability and battery life to stay with me on the move. People have been paying 5x more for ultralight sub-notbooks for some time; I suspect that the bottom just dropped out of that market.

Of course the experience can be crippled if you (or more likely your OEM) choose to install crippled software; which sadly appears to be the way things are headed. This seems like a fairly perverse marketing trick to me. The netbook I have today is perfectly capable of running a full fat OS, full fat office suite, full fat browser(s) and a media player (at least in standard definition). It can in fact do all of these things at once. Time, and Moore’s law, will only make netbooks more capable, though to be honest once they have 720p displays and enough processing power to drive HD video then I think the top of the utility curve will be reached (netbooks are a great example of Classen’s ‘logarithmic law of usefulness’). The point that I keep making to people is that when desktop processors hit 1GHz a few years ago that was probably as much compute power as any one user (at one time) could reasonably use. The low power processors in netbooks are clocked a little faster than the old 1Ghz parts, but manage to deliver similar subjective performance, with far less power consuption. In the meanwhile software continued soaking up the cycles, but recently that trend has reversed. This means that the same, good enough, subjective user experience will continue to get cheaper – making the disparity between hardware cost and software cost look less and less reasonable.

I hope that the OEM’s at least offer the option to buy a real OS to go with these machines, expecially if the difference is the $30 or so that Tim estimates; though I suspect that other commentators will see this as another way that people will be driven into the arms of the open source OS community.

Filed under: technology | 5 Comments

Tags: netbook

Security conferences

Having dragged James into the debate about Pamela’s post, and having spent most of the week at a security conference I thought I’d throw some of my own thoughts into the ring.

Let’s start with attendees, or ‘plankton‘ as Pamela calls them, and the idea that attendees learn something by going to conferences. I think this is partially true – for people that are new to the field or a given role; but doesn’t actually apply to many attendees, where you quickly get the usual suspects showing up year after year. Some events have clearly now got to the stage where their only value to many attendees is meeting with the other usual suspects, and as Pamela points out you can do most of that without buying a ticket. I’m also less than convinced that there’s really much educational value in vendor presentation. Mileage varies (according to the quality of the event) between outright product pitches and ‘here’s one of our smartest people letting you know why we think this is a problem (that needs our solution)’, but it’s still SUV mpg that you get for your money. If you outsource your thinking to vendors then don’t be surprised to get a bunch of dumb stuff for your money. This is why I’ve been leaning towards more academic conferences over the last few years. They have their own rough edges, but there’s no vendor spin, and you get a lot of new information for your money.

James asked me to report back on whether the shift from network security to application security was in evidence. I can’t give a completely straight answer to that, as I’ve spent all of my time this week meeting people and introducing them to my successor. I’m kind of glad that I wasn’t spending time looking for cool new stuff, there doesn’t seem to be any. As for whether people are getting the need to move from the network to the application that seems to depend who you talk to. If this was politics then I’d say it was split along party lines; but it’s technology so it’s split along vendor lines. If measured by floor space then I’d say that we’re mid transition, as it was the host security guys that seemed to be trying the hardest (to differentiate commodity products by having larger and louder stands than the next guy).

Filed under: security | 4 Comments

Tags: conference, security

Netbook nirvana

In my recent technology timeline post I bemoaned the fact that there seems to have been an innovation drought for the last few years (at least where it comes to life changing gadgets) and wondered whether the netbook I had ordered (but not received) might change that? Well… I’ve had the netbook for a few weeks now, and I think it’s a deserving addition to the timeline list. Here’s why:

- It’s small and light enough that I am willing to take it with me all the time. I’ve had supposedly class leading light laptops for years, and this simply hasn’t been the case.

- The battery is enough to get through a typical day on the road without having to plug in. That’s not a day of always on use, but for regular email and blog checks, summary notes etc. it’s fine.

- The screen might be small, but it’s sufficient, and certainly beats smaller devices for watching videos on the way home. Roll on the day when these things come with 1280×720 as standard (yes I know the laws of physics stop my eyes from seeing every pixel at the right relief distance, but I’ve had a high def screen before and liked it).

- The keyboard is big enough to type normally, and adjusting to missing and displaced ancillary keys didn’t take long. I’m still not a huge fan of trackpads, but a nice little Bluetooth mouse saves me from worrying too much about that.

All this leaves me wondering why anybody would pay >£1k for an executive laptop, when you get pretty much the same thing for <£300?

The one thing that I don’t understand is why integral 3G modems aren’t a standard thing? I’m running with an expresscard thingy, which pokes out a little less than a USB fob, and offers more control and status indicators, but this really should be built in. The cards to do this seem pretty cheap in bulk, so why isn’t it at least an option?

Filed under: technology | 1 Comment

Will credentials

I’m going to be dealing with the final taboo, I hope that doesn’t make you uncomfortable.

The question at hand is what happens to our digital assets when we die, and how do we deal with the identity management issues intertwined with this?

So far it seems that this hasn’t been a problem large enough to deserve legislative and policy attention, but I suspect that’s a result of demographics. Old people don’t use as many online services as younger digital natives; but that’s changing as online services become more ubiquitous and grannies sign up for social networking utilities so that they can see photos of their family. It’s also a problem that will get worse over time; none of us is getting any younger, and the variety and usage of online services grows each day.

For services anchored in the real world like banking and utilities it would seem that the normal rules apply; accounts get closed down, or transferred, as appropriate. But even here there are issues, as online statements and billing remove the paper trail. If I have an online only deposit account then who even knows apart from me, the holding institution and the taxman?

Pure virtual services are clearly more problematic. If my contact book is in the cloud then who gets invited to the wake (and do digital Dunbar numbers mean a much bigger catering order)? If my photos are online how do they get passed on to my kids? Can my MMORPG artefact weapon be handed down from virtual father to virtual son (or at least can my crew keep my inventory)? This should be taken care of by the EULA or service agreement. I checked a few and found nothing. In most cases we have precious few rights even when we’re alive and kicking, so it’s no surprise that there’s no provision for when we’re dead. Maybe Richard Stallman is right to caution that we should all keep local copies of our data.

So what should be happening? Here are a few ideas:

- Service registries – a place where the online services used by an individual can be gathered together.

- Escrow credentials – so that next of kin (or executors) can access services on behalf of the deceased.

- ‘Last post’ provisions – for that final (micro)blog post, email or whatever to say goodbye.

- EULAs and service agreements with transferable rights.

Perhaps all of these things could be brought together into one service, a sort of digital undertaker. The link to identity is however key. As our needs for stronger proofing and tokens become more widespread the problem of identity inheritance (or in some cases identity delegation) become less abstract and less tractable. These things could also become features of emerging federated identity services, but in that case what would be the regulatory framework, and how do we deal with crossing jurisdictional boundaries?

Filed under: identity | 8 Comments

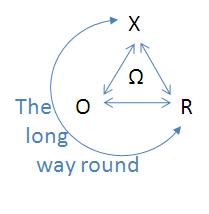

Impedance was one of those things that I really didn’t understand until I did my degree in electronics engineering. For those of you that are interested WikiPedia is as ever a good resource, though the short version is that matching is all about ensuring efficient transfer of energy from source to load. I can’t recall whether Pete Lacey coined the term when talking about different data representations or if he was simply the first that I heard it from; regardless, it’s a great analogy. There is work involved in getting data between different representations such as relational [R] (as used in common database management systems), object [O] (as used in most popular programming languages) and XML [X] (as used for many web services). This work is often referred to as serialisation (converting to a given format) and deserialisation (converting from a given format), and the effort is often not symmetrical – in computational terms it’s fairly cheap to create XML, and pretty expensive to convert it back to other forms. This is what led me a few years ago to talk about the X-O-R triangle, and the ‘long way round’ – where data only gets between XML and a relational database via an object representation in some programming language and runtime. The ‘long way round’ involves two lots of impedance mismatch, each with their cost in terms of CPU cycles (and garbage objects) and potential loss of (meta)information along the way. Whilst organisations continue to use relational databases as their default system of persistence this is one of the key reasons why a service oriented architecture based on XML web services will struggle to get by.

Sean is right that we need open data to make the next generation of financial platforms work. I think it’s worth unpacking the various models (and underlying data representations) used in trading derivatives in order to see where the mismatches exist, as these are fundamental to the inefficiency of existing market participants (and probably go a long way towards explaining some of the misalignment of incentives that has landed us in a global financial crisis):

- The risk model. This is what the trader needs to price (and therefore sell) a derivative instrument. Such a model is normally a hybrid of a spreadsheet, which is used to marshal market data and other input variables and a quantitative calculator, which is used to munge the variables held in the spreadsheet into a price. In simplistic cases the calculator can itself be part of the spreadsheet (and make use of the spreadsheet program’s calculation engine); but this isn’t a simplistic business, so the calculator tends to be an external model written in C++ or a mathematical simulation language. It’s easy to get fooled into thinking that spreadsheets are a simple case of relational data, as they both share the rows and columns. The trouble with spreadsheets is that they have no formal schema – the data is only structured in the mind of the spreadsheet author.

- The structural model. This is what the guys in the back office need in order to book, confirm and settle a trade. The structural model is implicit within the risk model, but it needs to be made explicit so that data can be passed around between systems. Over the years the format of these models has followed the fashions of the IT industry, starting with relational, passing through object and most recently adventuring into XML. Each fad has had compelling advantages, but each has ended up suffering from the same fundamental problem – X-O-R – this isn’t the language of the risk model (or the person that made it).

- The lifecycle model. Derivative instruments are ultimately a set of contingent cash flows, and therefore can be defined by their lifecycle, and yet this is rarely explicitly modelled. In part this has been because the appropriate tools have only just become available, with WS-CDL looking like the first standards based approach. One of the key things that an interaction model like this allows is an understanding of transaction costs (which may be large in the tail of a long lived instrument), which need to be set against any margin associated with the primary cash flows of the trade. Without such a model it’s entirely feasible for a trader to book what looks like a profitable trade (and run off with his bonus) when in fact it then saddles the issuing organisation with a ton of long tail transaction costs.

Clearly there are potential mismatches between each of these models, and these can be resolved by moving back to front (rather than the way things are done today). If we start with a lifecycle model (in WS-CDL) then this implies a structural model in XML, and that in turn can be used to construct the framework for a risk model. This is where I get onto education, as I think the key issue here is that traders (and most quants) don’t ever have an opportunity to learn enough about data representation (and its tradeoffs) to make an informed decision about which to choose.

I could characterise three generic mechanism by which knowledge is imparted – education, training and experience. Computer science degree courses are so chock full of other stuff that they barely cover the basics of data representation (in object and relational forms). So… for hardcore XML (or RDF[1]) expertise that leaves us to training (and there’s precious little of that) and experience. This brings me to my other impedance mismatch. Industry (the ‘load’ for education) clearly needs more XML and similar skills, but students (our ‘source’) have no tolerance for extra time on this stuff being wedged into their curriculum; in fact most engineering and computer science courses are struggling to survive as their input gets drained away to easier, softer options. Maybe this is where things like the Web Science Research Initiative (WSRI) can help out, but until that comes to pass… JP, Graham – Help!

Perhaps the real problem here is the owner of the risk calculator that is so closely tied to the risk model – the modern day quant. In the great days of people like Emanuel Derman these guys came from academia and industry with sharp minds and a broad range of skills in their tool bag. Now quants are factory farmed on financial ‘engineering'[2] courses, producing a monoculture of techniques and implementations. If there’s a point of maximum impact for getting data representations onto the agenda then it’s probably these courses, but again the issue of what can be safely dropped rears its head. This is perhaps why Sean is right to focus on statisticians and those employing the semantic web in other disciplines; to slightly misquote Einstein the thinking that got us into this mess won’t be what gets us out.

[1] Thanks @wozman for the amusing alt definition. For a more serious rundown on the Semantic Web James Kobielus has just posted a good overview.

[2] Engineering here in quotes as I can’t think of any of these courses that are certified by an engineering institution (which is why they are MSc rather than MEng). Yes, I know I’m being an engineering snob – that’s what happens to people who spend their time in the lab (learning about impedance) whilst their fellow students are playing pool.

Filed under: technology | 2 Comments

Tags: data, derivatives, education, experience, impedance, model, quants, risk, semantic, training, web, xml

Maaking it work

Yesterday’s posts on wikis and the semantic web were probably less constructive than they could have been. I was long on identifying the issues, and short on fixing the problems.

I stressed the importance of user experience, and in many cases the social networking sites already give us that, though I would love to see JP’s ‘graphic equaliser’ brought to life. Unfortunately existing sites give us a good user experience on their terms, inside of their walled garden. GapingVoid hit the nail on the head here, but it’s not just about making money, it’s about freedom to work together on our own terms rather than somebody else’s Ts&Cs.

I’ll (re)use some use cases to illustrate how things might work…

- Planning the party – how do you get a dozen people in roughly the same place at the same time.. I still see the Wiki as a core to solving this problem. All that’s really needed is a place where everybody can contribute information like flight and mobile numbers so that it can be consolidated. Some kind of federated identity is clearly needed to get people through the door, and maybe OAuth provides a neat way of integrating with what people are using already if they’re not tooled up for OpenID, Information Cards or SAML. Secure syndication is clearly a problem, which is why everybody should have their own queue. Messaging as a Service (MaaS) based on AMQP gives us a way to do this. What happens to those messages? I think they become inputs to the ‘graphic equaliser’, which then throws them out in the user’s preferred modality (e.g. Fred just changed his flight details, I find out by text to my mobile because I’ve told my system that I’m on the road without full fat net access).

- ‘Bank 2.0’ – this is very similar to planning the party in that it’s all about creating puddles of knowledge to support decisions. Once again we see content aggregation, syndication, and customised consumption as the core requirements. In this case though there are many things about existing web technology, and in particular HTTP – a synchronous, unreliable protocol, that make things tough. For human decision support there might be some wiggle room on timeliness, but everybody wants accuracy. For automated decisions (e.g. algorithmic trading) things need to be as reliable as possible, and as fast as possible. Moving trades between systems, processing a settlement, sending a confirmation – these are all inherently asynchronous activities that ought to be reliable. Once again AMQP seems perfectly positioned to fit the bill, and once again some kind of MaaS looks like the solution for internal integration and external connectivity.

So, MaaS looks like the foundation here. In some ways I think these services will become like an inside out version of web hosting – a place to consume rather than a place to publish; though clearly we need both.

Filed under: e2.0 | Leave a Comment

Tags: AMQP, MaaS, oauth, web 2.0, wiki

I don’t think this is going to be what Sean was asking for, but I also didn’t want to ignore the call to action, and the points that follow will hopefully lead to some useful debate. This post will probably be provocative, so lets start right out with my point of view – semantic web is not the solution, now can we get a bit clearer about what’s the problem?

Firstly, a little history. I first came across semantic web technology about 6 years ago when working on web services (SOA) governance. Most of the governance issues seemed to boil down to a lack of shared meaning, and so semantic web looked promising as a means to establish shared meaning. Unfortunately it turned out that the cure was worse than the disease. This is one of the reasons why SOA is dead.

From my perspective the key difference between the web and the semantic web is that the former can be utilised by anybody with a text editor and an HTML cheat sheet, whilst the latter requires brain enhancing surgery to understand RDF triples and OWL. The web (and web 2.0) works because the bar to entry is low, the semantic web doesn’t work because the bar to entry is too high. TimBL exhorts that the problems we collectively face could be solved by everybody contributing just a little bit of ontology, but that song only sounds right to a room full of web science sycophants. Everybody else asks onwhatogy?

I’m also not convinced that financial services needs more ‘interoperability of information from many domains and processes for efficient decision support‘. Yes, decision support and the knowledge management that underpins it needs information from many domains, but is there really an interoperability problem? Most of the structured data moving inside and between financial services organisations is already well formatted and interoperable. There’s more work to be done everywhere with unstructured data; but there’s even more to be done at better facilitating the boundary between implicit knowledge (in people’s heads) and explicit (on rotating rust, or SSDs in not too long) and back. Semantic web concentrates too much on the explicit-explicit piece of the knowledge creation cycle. The web 2.0 platforms seem to be stealing a march over semantic web by having the usability to make traversing the tacit-explicit and explicit-tacit boundaries easy. It’s all about user experience; if the techies decide to build that experience on top of a triple store and some nice way of hiding (or inferring) ontologies then cool – but who cares – somebody else might do better on top of a flat file, in a tuple space or whatever.

Filed under: e2.0 | 3 Comments

Why don’t we wiki?

At the end of my technology time line that I posted yesterday I wondered if I should have included more services, particularly in what seems like an innovation vacuum over the last six years. On reflection I think I know why I didn’t include many. Almost everything on the time line was something where I triumphed over adversity – a product came along, its concept was good, but it didn’t quite cut it, but after a bit of tweaking it was made to work – most importantly lessons were learned, and it was these lessons that in part shaped who I am and what I do. When I look at services though there has been no triumph, just continuous improvement. There still is adversity. Things haven’t yet been made to work as well as they should.

This brings me to wikis. Next week I’m looking forward to spending some time on the ski slopes and apres ski bars of the alps in the company of a bunch of people that I mostly don’t know (yet) who are all converging for a stag (bachelor) party. Co-ordinating the logistics of flights, hotels, mobile numbers etc. by email is a nightmare, and I was once again struck by the idea that this would be the perfect use of a wiki. The trouble is that getting everybody to the same wiki is probably just as hard as getting everybody to the same bar. The problems are:

- The signup hurdle – creating a wiki requires somebody to sign up as an administrator, and all of the users to create accounts (or associate OpenIDs if they have them). This is a lot harder than blasting out a list of email addresses. Perhaps there’s a good, free (at point of use) and secure wiki platform that lets you drop in a bunch of email addresses and it automagically configures accounts and sends invites – let me know if you’ve seen it?

- The compliance trolls – many of us spend our working days behind corporate firewalls with web filters designed to prevent nasty things like ‘data leakage’ and ‘use of non compliance collaboration platforms’ etc. This cuts off a lot of web 2.0 – not good when you want to communicate.

- Alerts and updates – ’email inboxes are like todo lists where other people get to add items’ (Chris Sacca), so when I send somebody an email I get their attention. Sadly I’ve not yet seen a good (in band) way of doing this with wikis. It should be possible to do something with RSS, but nobody seems to have done it right yet (and I suspect that there would also be security issues that would prevent popular online aggregators working properly). It may have been 3 years ago that he posted, but Jermey Zawodny is still right – Wiki RSS feeds suck.

I feel that the social networking applications could do something about this, and maybe there’s even a BatchelorPartyOrganiser app out there for the platform de jour (see 2 above for why we’re not using it), but even if we could herd all the participants inside a walled garden I’m not sure that all the needs would be satisfied. What we really need is an open, connected and participative experience of content aggregation and syndication.

For now I guess we’re stuck with an ugly torrent of emails. I’ll probably print mine out before I go in case my batteries run out.

Filed under: e2.0, identity | Leave a Comment