FPGA

TL;DR

Field Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs) have been around for decades, but they’ve become a hot topic again. Intel recently announced Xeon chips with FPGAs added on, Microsoft are using FPGAs to speed up search on Bing, and there are Kickstarter projects such as miniSpartan6+ trying to bring FPGA the ease of use and mass appeal of the Arduino. Better accessibility is a good thing, as whilst the technology might be easy to get at, the skills to use it are thin on the ground. That could be a big deal as Moore’s law comes to an end and people start looking closer at optimised hardware for improved speed.

Background

I first came across FPGAs whilst doing my final year project in the compute lab of the Electronics department at the University of York. Neil Howard sat nearby, and was working on compiling C (or at least a subset of C) directly to hardware on FPGA[1]. Using Conway’s Game of Life as a benchmark he was seeing 1000x speed improvement on the FPGA versus his Next Workstation. That three orders of magnitude is still on the table today, as FPGAs have been able to take on Moore’s law improvements in fabrication technology.

My next encounter

FPGAs came up again when I was working on market risk management systems in financial services. I’d done the engineering work on a multi thousand node compute grid, which was a large and costly endeavour. If we could seize a 1000x performance boost (or even just 100x) then we could potentially downsize from thousands of nodes to a handful of nodes. The data centre savings were very tantalising.

I found a defence contractor with FPGA experience[2] that was looking to break into the banking sector. They very quickly knocked up a demo for Monte Carlo simulation of a Bermudan Option. It went about 400x faster than the reference C/C++ code. A slam dunk one might think.

Mind the skills gap

When the quants first saw the demo going 400x faster they were wowed. By the end of the demo it was clear that we weren’t going to be buying. The quant team had none of the skills needed to maintain FPGA code themselves, and were unwilling to outsource future development to a third party.

There was an element of ‘not invented here’ and other organisation politics in play, but this was also an example of local optimisation versus global optimisation. If we could switch off a thousand nodes in the data centre then that would save some $1m/yr. However if it cost us a more than a couple of quants to make that switch then that would cost >$1m/yr (quants don’t come cheap).

Programming FPGAs

Field programmable means something that can be modified away from the factory, and a gate array is just a grid of elementary logic gates (usually NANDs[3]). The programming is generally done using a hardware description language (HDL) such as Verilog or VHDL. HDLs are about as user friendly as assembly language, so they’re not a super productive environment.

Learning HDL

My electronics degree had a tiny bit of PIC programming in it[4], but I didn’t really learn HDL. Likewise my friends doing computer science didn’t get much lower level than C[5] (and many courses these days don’t ever go below Java). Enlightened schools might use a text like The Elements of Computing Systems (Building a Modern Computer from First Principles) aka Nand2Tetris, which uses a basic HDL for the hardware chapters; but I fear they are in the minority[6].

So since HDLs pretty much aren’t taught at schools then the only place people learn them is on the job – in roles where they’re designing hardware (whether it’s FPGA based or using application specific integrated circuits [ASICs]). The skills are out there, but very much concentrated in the hubs for semiconductor development such as the Far East, Silicon Valley and Cambridge.

The open source hardware community (such as London’s OSHUG) also represents a small puddle of FPGA/HDL skill. I was fortunate enough to recently attend a Chip Hack workshop with my son. It’s a lot of fun to go from blinking a few LEDs to running up Linux on an OpenRISC soft core that you just flashed in the space of a weekend.

The other speed issue

FPGAs are able to go very fast for certain dedicated operations, which is why specialist hardware is used for things like packet processing in networks. Programming FPGAs is also reasonably fast – even a relatively complex system like an OpenRISC soft core can be flashed in a matter of seconds. The problem is figuring out the translation from HDL to the array of gates, a process known as place and route. Deciding where to put components and how to wire them together is a very compute intensive and time consuming operation, which can take hours for a complex design. Worst of all even a trivial change in the HDL normally means starting from scratch to work out the new netlist.

Google’s Urz Hölzle alluded to this issue in a recent interview, explaining why he wouldn’t be following Microsoft in using FPGA for search.

Whilst FPGAs didn’t catch on for market risk at banks they’ve become a ubiquitous component of the ‘race to zero'[7] in high frequency trading. The teams managing those systems now have grids of overclocked servers to speed up getting new designs into production.

Hard or soft core?

Whilst Intel might be just recently strapping FPGAs into its high end x86 processors many FPGAs have had their own CPUs built in for some time. Hard cores, which are usually ARM (or PowerPC in older designs) provide an easy way to combine hardware and software based approaches. FPGAs can also be programmed to become CPUs by using a soft core design such as OpenRISC or OpenSPARC.

Conclusion

Programming hardware directly offers potentially massive speed gains over using software on generic CPUs, but there’s a trade off in developer productivity and FPGA skills are pretty thin on the ground. That might start to change as we see Moore’s law coming to an end and more incentive to put in the extra effort. There are also good materials out there for self study where people can pick up the skills. I also hope that FPGA becomes more accessible from a tools perspective, as there’s nothing better than a keen hobbyist community to drive forward what happens next in industry – just look at what the Arduino and Raspberry Pi have enabled.

Notes

[1] The use of field-programmable gate arrays for the hardware acceleration of design automation tasks seems to be the main paper that emerged from his research (pdf download).

[2] From building line speed network traffic analysis tools

[3] As every type of digital circuit can be made up from NANDs, and NANDs can be made with just a couple of transistors. The other universal option is NORs.

[4] If I recall correctly we used schematic tools rather than an HDL.

[5] My colleagues at York actually learned Ada rather than C, a peculiar anomaly of the time (the DoD Ada mandate was still alive) and place (York created one of the original Ada compilers, and the Computer Science department was chock full of Ada talent).

[6] It’s a shame, my generation – the 8bit generation, pretty much grew up learning computers and programming from first principles because the first machines we had were so basic. Subsequent generations have learned everything on top of vast layers of abstraction, often with little understanding of what’s happening underneath.

[7] Bank of England paper ‘The race to zero‘ (pdf)

Filed under: technology | 1 Comment

Tags: FPGA, HDL, Nand2tetris, programming, skills, speed, Verilog, VHDL

Home brew

TL;DR

I made a hoppy American style pale ale using a Festival Razorback IPA kit. It was easy, and tastes great.

Background

I like beer. I like beer a lot. Over the years my tastes have changed from the mass produced lagers of my youth, to the resurgent British real ale that’s been around for most of my adult life, and now American craft beer. It was probably a decade ago that I started visiting the US pretty frequently, and not long afterwards I discovered that American beer had moved on from Bud[1], Miller and Coors (Lite). Sam Adams was my first taste of the beer revolution, but it was Sierra Nevada that really made a mark on me.

Until last year I was pretty happy to leave American beer styles to my travels, but a couple of things conspired to change that. First and foremost I blame James Governor for introducing me to brews like The Kernel at his excellent Monkigras events; and then Ryan Koop got me going with Revolution Anti-Hero and SKA Modus Hoperandi in the bars of Chicago’s Loop. After returning home from an extended stint in Chicago last summer I found myself unable to appreciate an ordinary British pint. I had become addicted to hops.

Of course it’s possible to get hoppy IPAs and the like in the UK. Imports like Goose Island Green label are readily available, and there are plenty of domestic clones such as Brewdog Punk. The trouble is that they’re expensive – typically around £1.79 for a 330cl bottle. I mostly settled in to getting bottles of Oakham Citra from Waitrose – still £1.79 a bottle, but for a half litre. I’d also treat myself to bottles of Dark Star brews or some draft HopHead from my local boutique vintner.

The craft in craft beer

I’d met Elco Jacobs, the man behind Brew Pi, at Monkigras 2013, and we’d swapped notes on temperature control using Raspberry Pis. So I had some idea what would be involved. I’d also brewed some (terrible) ginger wine as a teenager. I figured that if I wanted to drink craft beer then I should get on with the craft. A quick chat with Jim Reavis at a Cloud Security Alliance event persuaded me to take the plunge.

Start easy

I decided to start out with a kit. My initial idea was to get a basic IPA kit, and then hop it up a bit, but then I found the Razorback kit and that seemed like a quick path to what I wanted. I bought the beer kit along with a comprehensive equipment starter kit[2] from Balliihoo.

The brew

After sterilising all the bits of equipment I was about to use it was pretty easy to get the kit going. I just dissolved the sugar pack and the pack of beer goop in hot water, put it into the brew bucket and added cold (filtered) water, stirred, added the yeast and sealed the lid.

The wait

Nothing happened.

For days my beer just sat there.

Not so much as a bubble from the air trap.

I thought my fermentation might be stuck.

Or maybe I’d killed the yeast by putting it in when the wort was too hot (even though I’d checked the thermometer on the side of the bucket).

And then finally after about a week it frothed up.

Dry hopping

After a couple of weeks I decided to take the plunge and add in the hops pack and test the gravity of my brew. It had gone from 1048 to 1012 – good progress.

More wait

Brewing needs patience. I left it alone for another couple of weeks, and it continued to show no external signs of anything happening.

Another gravity test showed 1005. First fermentation was finished.

Kegging

The auto syphon I’d seen recommended as an addition to the base equipment kit really came into its own here, and made the transfer to the keg very easy.

Yet more waiting

About a week for secondary fermentation to happen, and then another couple for conditioning and clearing.

At last

I have beer. It’s very nice straight from the keg. Nicer still if I decant some into a bottle and let it chill in the fridge. Properly awesome if I give it a quick fizz in the SodaStream before drinking[3]. It’s a little cloudy compared to commercial beers, but the important thing is that it tastes great.

My brother and I did a quick comparison against some HopHead last night, and we both actually prefer the floral notes on the home brew. My 40 pints might not last as long as I’d originally planned, so it’s a good job that I have another brew going on tonight.

ToDo

So far I haven’t turned my beer project into an electronics or Raspberry Pi project. That will come in time. I fully intend to make a brew fridge once I start to stray from just using a kit (and as the winter months necessitate some better temperature control).

Any tips welcome

I’m new to this, so please comment on what else I should be doing/trying.

Notes

[1] Back when I was in HMS London I used to be the ‘wardroom wine caterer’ (== booze buyer). For a NATO Standing Naval Force Atlantic deployment I went for a policy of buying local. The 50 cases of Labatts Ice I got in Halifax Nova Scotia went down very well, the 40 cases of Bud I got in San Juan not so much.

[2] I’ve still found no use for the funnels that came in the kit.

[3] Careful use of a SodaStream (I have a Genesis model) adds some extra fizz and hasn’t resulted in the mess that most forum posts warn about – like everything else with this brewing malarkey the main trick seems to be taking things slowly and carefully.

Filed under: beer | 10 Comments

Tags: APA, beer, brewing, craft, Festival, home brew, IPA, Razorback

Facebook have announced their own switch design, codenamed ‘Wedge’, saying that it’s already being tested in their production network. In many ways the switch is unremarkable; it uses the same Broadcom Trident II merchant silicon ASIC that most other high end ‘white box’ top of rack (TOR) switches use, and it uses Linux on a commodity compute platform as its operating system. The physical packaging and power systems fit in with the server designs that Facebook has previously donated to the Open Compute Project (OCP), making it almost the purest expression of networking equipment as a commodity.

Continue reading at The Stack

Filed under: networking, The Stack | Leave a Comment

Tags: ASIC, Facebook, OCP, open compute, osh, SDN, switch

InfoQ articles

I bumped into a friend and former colleague earlier in the week who reads this blog, but didn’t realise that I now write cloud stuff for InfoQ.

Please take a look – most of the recent stories are about Docker, but I also do my best to cover the most important cloud news in a given week. I also do video interviews with people at QCon conferences, and if you go far enough back some of my own presentations are there (though sadly not the one from the original QCon London).

I’ll try to figure out a way to bring InfoQ stuff into this activity stream.

Filed under: cloud, InfoQ news | Leave a Comment

Tags: cloud, InfoQ, news, QCon

The cloud price wars that began at the end of March have been all about compute and storage pricing. I don’t recall hearing network pricing being mentioned at all; and indeed there haven’t been any major shifts in network pricing.

|

| Photo credit: Datacenter World |

Network is perhaps now the largest hidden cost of using major IaaS providers, and also one of their highest margin services.

Let’s take a practical (and personal) example. At the start of last year the Raspberry Pi images for OpenELEC that I was hosting on my Pi Chimney site were being downloaded around 35,000 times a month generating 3.5TB of network traffic.

Let’s have a look at my options using present prices:

- AWS EC2 assuming I could use a free tier instance and that it wouldn’t melt under the load then my data transfer out of Amazon EC2 to Internet would be $0.12 per GB for a total of $429.96

- I could have put the files into S3 and paid the same transfer cost of $429.96 (but not worried about server load)

- CloudFront wouldn’t make any difference either, as that’s also $0.12/GB for a total of $429.96, though maybe the service would be faster

- GCE pricing is pretty close to AWS. The first TB is $0.12, and the 1-10TB is a little cheaper at $0.11 for a total of $404.48 – a paltry saving of $25.48

- Once again pricing is the same for Google Cloud Storage

- Azure is also $.12 for the first 10TB, though it offers 5GB free where Amazon only offers 1GB (and Google offers none), so it’s fractionally cheaper at $429.48

- The first offer I find on LowEndBox (a marketplace for cheap virtual private servers) with a 4TB bandwidth allowance is XenPower’s XP-XL at $6.68 – a saving of almost $400 against the cheapest major IaaS vendor!

When this was a real issue for me I used a VPS provider that included 3TB of network with the $10/month server I was using, I would switch traffic at the end of the month to a second VPS I had that included 1TB of network in the $6.99/month. The site has subsequently moved to GreenQloud where they provide complimentary hosting in exchange for me advertising their sponsorship[1].

High margin

Let’s for the sake of argument say that the $6.68 for a VPS is just bandwidth – the compute, storage and IP address come for free (which they don’t). Furthermore let’s say that’s cost price for the VPS provider. In that case we can take an Amazon charge of $480 (for 4000GB) and calculate a gross margin of 98.6%.

Of course VPS providers don’t get compute and storage and IPs for free[2], so it’s reasonable to assume that Amazon (and it’s competitors) are getting >99% gross margin on bandwidth. Nice business if you can get it.

Higher margin

Of course the calculation above assumes that the VPS provider and Amazon pay the same for their bandwidth, which of course they don’t. Amazon has a far better bargaining position with its telecoms providers than XenPower (or any other VPS provider likely to show up on LowEndBox). It’s fair to assume that Amazon pays much less for its bandwidth than XenPower does.

What is the cost of bandwidth anyway?

Bandwidth within co-location centres gets charged by the MBps. A typical rate at present is $2/month for a 100Mbps link, or $1.50/month for 1Gbps. 10Gbps links are cheaper still, but nobody seems to want to publish pricing information on the Internet. Driving one of those 1Gbps links at full speed would translate into a cost of $0.00474 per GB/month. That’s still a lot more than the $0.00167 per GB/month from XenPower.

Tiered pricing

My example fits into the 0-10TB price band for the big clouds. Amazon (and its competitors) have a tiered pricing structure where the cost drops to $0.05/GB for 150-500TB, and there are three bands beyond that with a price of ‘contact us’. It’s not at all clear why there’s consistent pricing for instances but ramped pricing for network. What is clear is that the cloud providers can sell transfer in bulk at less than $0.05/GB.

Bandwidth != transfer

Bandwidth is the capacity of a network link, whist transfer is the actual traffic pushed across it. In real life network utilization is bursty, and so it’s necessary to buy more bandwidth than the notional transfer being supported over time (otherwise the network becomes a bottleneck).

So how do the VPS providers do it?

It’s a mixture of factors:

- Throttling – the VPS provider will have an Internet connection with a given bandwidth, and once that’s saturated then customers will start to notice additional latency. Individual servers might also be throttled.

- Capping – once a bandwidth allocation is used then the VPS might be switched off until the end of the billing cycle.

- Mostly unused – the VPS provider can build a statistical model of how much transfer actually gets used, which won’t always be the max for every customer.

All of this adds up to VPS providers paying for a limited amount of bandwidth.

|

| Photo credit: Rusted Reality post |

So what’s different about IaaS?

IaaS providers are charging by transfer actually used without imposing caps, and having to buy sufficient bandwidth to support that transfer without throttling, which involves some degree of oversupply from a capacity management perspective. That said, it still looks like a very high margin part of their business, and one that hasn’t become cheaper as a result of the cloud price wars.

Notes

[1] GreenQloud offers 1TB free with its servers then charges $0.08 per GB for transfer, so one of their Nano servers would come in at $212.10/month for my 3.5TB workload.

[2] IPv4 addresses are starting to become a significant cost contributor to very low end VPS offerings, which is why IPv6 only packages are starting to crop up.

This post originally appeared on the CohesiveFT blog as part of the Cloud Price Wars Series

Filed under: cloud, CohesiveFT, networking | 5 Comments

Tags: amazon, Amazon Web Services, aws, Azure, bandwidth, cloud, GCE, google, iaas, margin, Microsoft, pricing, transfer

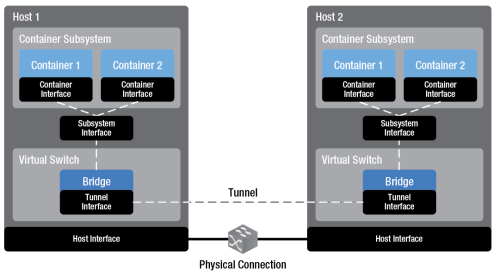

I wrote a few days ago about my first failed attempt to do this.

After some perseverance, and with some lessons learned along the way I’m pleased to say that I now have it working.

Given that VXLAN (at least in the Linux kernel implementation) needs multicast I’m still not sure that this is a good idea, as it won’t work in (almost every one of the) public clouds.

Stability at last

The main thing that stopped me on my first try was repeated kernel panics when connecting a couple of VMs together over VXLAN.

I was using stock Ubuntu 14.04, with a 3.13.0-24 kernel and iproute2-ss131122 – a configuration that was unusable.

Going back to 12.04 with the trusty backport kernel 3.13.0-27 and the latest iproute2-ss140411 [1] seems to give me a stable platform for experimentation.

Getting it going

First take down and delete the existing docker0 bridge:

sudo ifconfig docker0 down sudo brctl delbr docker0

Then create a new bridge (using the MAC address of the old one), and give it an IP:

sudo brctl addbr docker0 sudo ip link set docker0 address 56:84:7a:fe:97:99 sudo ip address add 172.17.42.1/16 dev docker0

Add the VXLAN adaptor and give it a MAC address:

sudo ip link add vxlan10 type vxlan id 10 group 239.0.0.10 ttl 4 dev eth1 sudo ip link set vxlan10 address 54:8:20:0:0:1

Then plug the VXLAN adaptor into the bridge and bring both of them up:

sudo brctl addif docker0 vxlan10 sudo ifconfig vxlan10 up sudo ifconfig docker0 up

The process then needs to be repeated on a second machine, taking care to change MAC and IP addresses to avoid conflicts. I used 56:84:7a:fe:97:9a and 172.17.42.2 for docker0 and 54:8:20:0:0:2 for vxlan10.

With that done I could ping between machines on their 172.17.42.x addresses

Connecting containers

I already had a container running Node-RED on the second machine, which I (re)attached to the docker0 bridge using:

sudo brctl addif docker0 vethb909

I could then ping/wget stuff from it on its IP of 172.17.0.2

A new container that I brought up on the first VM was similarly reachable from the second VM at 172.17.0.3

IP assignment remains a problem

Just as with Marek Goldmann’s bridging using Open vSwitch it’s still necessary to do something to manage the container IPs, and I have nothing to add to his recommendations. I’m sure it’s just a matter of time before people come up with good orchestration mechanisms and DHCP that works across machines.

Recommended reading

I hadn’t previously found the full Docker network configuration documentation, but it’s very good (and it’s a shame that it’s not linked from the ‘Advanced Docker Networking‘ documentation’ [2]).

Conclusion

Something is badly wrong with VXLAN in Ubuntu 14.04.

Using a working VXLAN implementation it is possible to connect together containers across multiple VMs :)

Notes

1. I followed Alexander Papantonatos’s guide for building iproute2, but went for the latest version (3.14 at the time of writing).

2. I’m linking to the Google Cache version as at the time of writing the link is dead on the Docker.io docs (which seem to be having a major overhaul – perhaps Docker will go 1.0 at DockerCon tomorrow?).

Filed under: Docker, networking | 3 Comments

Tags: 14.04, bridge, Docker, iproute2, multicast, network, open vswitch, tunnel, Ubuntu, vxlan

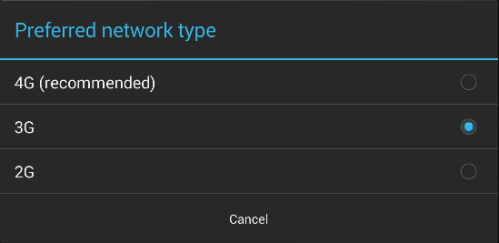

TL;DR

If you’re a Three customer using a 4G capable device abroad with their Feel at Home free international roaming then you may have to manually select 3G as the network preference in order to get a data connection.

Update 1: Terence Eden provides a telco insider explanation what what’s going on (or should that be what’s going wrong) in comments below. The bottom line – 4G is excluded from most roaming agreements (at least for now) and the devices don’t deal with this gracefully.

Background

I’ve been a Three customer for many years now, so I was very happy when I found out about Feel at Home. As a fairly frequent visitor to the US I’d grown accustomed to forking over $30 to AT&T for a month of data, and using a combination of a local SIM and Skype ToGo in order to call home.

I first tried out Feel at Home on a family holiday to Florida, and it just worked, and worked well. I was able to catch up on emails and Twitter whilst waiting in theme park lines, and there were no nasty roaming bills waiting for me when I got home. Best of all I didn’t have to deal with AT&Ts customer hostile buyasession web site.

No Service

When I arrived in SFO yesterday my phone was working fine, but my tablet wasn’t getting a data connection. If I turned flight mode on and off (or rebooted it) then I’d briefly get a connection to AT&T or T-Mobile, but then it would report No Service.

I double checked that data roaming was enabled. I tried manually selecting a network. I was just about to email Three Support about it when I had a final look in my settings to see if there was anything else I might change…

Disable 4G

The only other setting available was Network Type. I changed from 4G (preferred) to 3G:

and I was connected again :)

It’s nice to have R back, though I do miss being able to tell what connection speed I’m getting – with an AT&T local SIM I’d get the logos for LTE, H(SDPA), 3G, EDGE or G(PRS) as appropriate. R just tells you that you’re connected with no indication of quality[1].

In retrospect the same issue might have been happening whilst on a recent trip to Chicago, but I wasn’t out of WiFi bubbles long enough to properly diagnose it. I guess that San Francisco (and Chicago) have received 4G updates ahead of Orlando and Tampa.

Now I just need to remember to switch back to 4G when I get home – as I increasingly see that I get a 4G connection in and around London on Three’s network :)

Note

[1] My Samsung S4 Mini is able to show that it’s roaming and what type of connection it’s getting, which seems loads better to me than what I get from my Nexus 7 LTE.

Is this a rare example of OEM mangled Android being better that stock?

Filed under: howto, technology | 7 Comments

Tags: 3G, 4G, data, feel at home, no service, roaming, Three

This seemed like a good idea, as VXLAN has been in the Linux kernel since 3.7. TL;DR – this doesn’t work as I’d hoped. The two major issues being:

- VXLAN needs a multicast enabled network, which rules out most public clouds.

- Instability – I’ve managed to provoke multiple kernel panics on stock Ubuntu 14.04.

Background

As Docker deployments outgrow a single machine it can make sense to join container networks together. Jérôme Petazzoni covers the basics of using Open vSwitch in his documentation for pipework, and Marek Goldmann goes further with a worked example of Connecting Docker containers on multiple hosts.

What I did

Setting up VXLAN

Alexander Papantonatos posted last year on VXLAN on Linux (Debian). Using Ubuntu 14.04 most of the preamble stuff isn’t necessary, as the right kernel modules and a recent iproute2 are already present, so I was able to get right on with configuring interfaces and bringing them up:

sudo ip link add vxlan10 type vxlan id 10 group 239.0.0.10 ttl 4 dev eth1 sudo ip addr add 192.168.1.1/24 broadcast 192.168.1.255 dev vxlan10 sudo ifconfig vxlan10 up

I went through a similar process and assigned 192.168.1.2 to a second host, and confirmed that it was pingable.

Connecting the Docker network to the VXLAN interface

Using Marek’s Open vSwitch script as a template I ran through the following steps (after installing the bridge-utils package[1] and Docker):

sudo ip link set docker0 down sudo brctl delbr docker0 sudo brctl addbr docker0 sudo ip a add 172.16.42.1 dev docker0 sudo ip link set docker0 up sudo brctl addif docker0 vxlan10

After repeating with a different IP on the second host I tried to ping the docker0 IPs between hosts, which didn’t work. I tried the IPs assigned to the vxlan10 interfaces, which were no longer working. I tried deleting the docker0 bridges and starting over, and that’s when the kernel panics started. I’m now at the point where as soon as I try to use the VXLAN network between VMs one of them blows up :( It seems that I was lucky that the original ping test worked. On subsequent attempts (including rebuilds) I’ve been able to provoke kernel panic as soon as VXLAN is brought up on the second host.

Conclusion

I don’t think VXLAN is fit for this purpose. Even if it was stable it wouldn’t work in public cloud networks.

Please comment

What did I get wrong here? If I’m doing something stupid to provoke those kernel panics then I’d love to hear about it.

Note

[1] sudo apt-get install -y bridge-utils

Filed under: Docker, networking | 2 Comments

Tags: bridge, Docker, fail, gre, iproute2, multicast, network, open vswitch, tunnel, Ubuntu, vxlan

Beware the default network

I was helping a colleague troubleshoot a deployment issue recently. He’d set up a virtual private cloud (VPC) in Amazon with a public subnet and a bunch of private subnets:

- 10.0.0.0/16 – VPC (the default)

- 10.0.0.0/24 – Public subnet

- 10.0.0.1/24 – Private subnet 1

- 10.0.0.2/24 – Private subnet 2

- 10.0.0.3/24 – Private subnet 3

Everything was behaving itself in the first two private subnets, but nothing in the third one was reachable from the hosts in the public subnet. After lots of fine toothed combing through the AWS config we took a look at the routing table on a host in the public subnet:

Destination Gateway Genmask Flags Metric Ref Use Iface

default ip-10-0-0-1.eu- 0.0.0.0 UG 100 0 0 eth0

10.0.0.0 * 255.255.255.0 U 0 0 0 eth0

10.0.3.0 * 255.255.255.0 U 0 0 0 lxcbr0

172.16.10.0 * 255.255.255.0 U 0 0 0 docker0

172.31.0.0 m1 255.255.0.0 UG 0 0 0 tun0

172.31.0.0 * 255.255.0.0 U 0 0 0 tun0

192.0.2.0 192.0.2.2 255.255.255.248 UG 0 0 0 tun1

192.0.2.2 * 255.255.255.255 UH 0 0 0 tun1

192.0.2.8 192.0.2.10 255.255.255.248 UG 0 0 0 tun3

192.0.2.10 * 255.255.255.255 UH 0 0 0 tun3

192.0.2.254 * 255.255.255.254 U 0 0 0 eth0

224.0.0.0 m1 240.0.0.0 UG 0 0 0 tun0

The problem here is a conflict between 10.0.0.3/24 configured as a VPC subnet, and another 10.0.0.3/24 configured on the host for lxcbr0 – a relic from an early Docker installation[1] that used LXC (and allowed it to install its default bridge)[2]. We worked around this by creating a 10.0.0.4/24 instead – an easy fix – this time.

You won’t be so lucky with VPC Peering

Amazon announced the availability of VPC Peering a little while ago. It’s a pretty cool feature, and it’s worth taking a look at the peering guide, and the recent Evolving VPC Design presentation from the London AWS Summit for more details. There is one key part that needs to be called out:

The VPCs to be peered must have non-overlapping CIDR blocks.

That means that if you’re using the default 10.0.0.0/16 then you can’t peer with anybody else (or indeed any of your own networks in other accounts) using that default, which right now is pretty nearly everything.

Amazingly it is possible to peer together overlapping CIDRs indirectly, so I can join my 10.1.0.0/16 network A to a number of 10.0.0.0/16 networks (B,C etc.); but there’s a couple of catches: firstly peering isn’t transitive (B can’t talk to C), and secondly I can have a subnet of A connected to B, and a different subnet of A connected to C, but not the same subnet in A connected to B and C[3].

Recommendations

It’s easy to say plan your network carefully, but that’s a bit like saying plan your family carefully. Circumstances change. Networks grow organically. Things have to be joined together later because company X bought competitor Y (which seemed unimaginable to both of their network engineering teams).

- Avoid the defaults – using 10.0.0.0/16 for a VPC will pretty much guarantee trouble with peering.

- Don’t use the next range along – 10.1.0.0/16 is only one better than the default; 10.254.0.0/16 isn’t 254 times better. There are 253 other networks to play with (just in the RFC1918 class A), and picking one at random is likely to be a good strategy.

- Use smaller networks – a /16 is a LOT of IPs. The smaller the network the less chance of collision with another.

Notes

[1] Since version 0.9 Docker doesn’t actually use LXC any more by default, preferring its own native libcontainer.

[2] If you’ve been playing around with Docker since the early days and you have these bridges laying around then they can be removed using:

sudo ifconfig lxcbr0 down && sudo brctl delbr lxcbr0

[3] This kind of thing comes up all the time when making VPN connections in partner networks where it’s only a matter of time before overlapping RFC1918 ranges come along (usually 10.0.0.0/8 or 192.168.0.0/24 or close cousins). It is actually possible to deal with situations like this using source network address translation (SNAT) and network mapping (where one range gets mapped to another to avoid conflict). This is something we’ve supported in VNS3 for a little while.

Filed under: cloud, CohesiveFT, Docker, networking | 1 Comment

Tags: aws, CIDR, conflict, defaults, Docker, howto, LXC, lxcbr0, networks, peering, routing, troubleshooting, VNS3, VPC

The dust is starting to settle now in the wake of Heartbleed[1] – those that are going to fix it have already, other servers that are suffering from the issue will remain vulnerable for years to come. It’s time now for reflection, so here’s mine.

I was on a family vacation when Heartbleed was announced, and the first tweet I came across in my timeline was from Docker’s Jérôme Petazzoni:

It was very prescient, and in retrospect the situation reminds me of the fabled Tortoise and the Hare.

The Tortoises

Heartbleed only affected relatively recent versions of OpenSSL[2], so those companies plodding along on older releases weren’t affected. This included CohesiveFT. We base our products on Ubuntu Long Term Support (LTS) distributions, and everything in production was based on 10.04[3].

Some argue that the tortoise approach can be insecure, but the beauty of long term support is that critical security issues (like Heartbleed) get patched up.

In this particular case the Tortoises were in good shape, as their distributions carried older OpenSSL variants that weren’t affected.

The Hares

The Hares are the companies that always keep on the latest builds. For service providers this probably meant that they had a single version of OpenSSL in the wild (or a handful of versions across a portfolio of services) and they had a busy day or two patching and refreshing certificates. Product companies will have had a slightly different challenge – with newer versions requiring patches and perhaps some older releases that could be left untouched.

The accidental Hares

If you’re a Hare then you have to keep running. Stop for a break and you’ll lose the race.

The accidental Hares are those that just happened to pick up a distribution or stack with OpenSSL 1.0.1 in it, but they don’t actively patch, update, and keep on the latest version. It’s the accidental Hares that will be polluting the web for years to come with servers that pretend to be secure but really aren’t.

Mixed environments

This is where the real effort will have been expended.

A friend of mine recently started a new risk management role at a large bank. This Twitter conversation sums up what happened:

I recall a similar experience as a result of the RSA SecurID breach.

I expect that one of the major challenges will have been firstly figuring out what had OpenSSL inside of it, and then what versions. No doubt there’s now some kind of inventory of this in most large organisations, but for the majority it will have taken a massive fire drill to pull that inventory together.

What have we learned?

This time the Tortoise ‘won’, but this single event shouldn’t be used to support a Tortoise strategy. The Hares tend to be more agile.

It’s better to choose to be a Tortoise than it is to be an accidental Hare. ‘Enterprise’ and ‘Long Term Support’ versions of stuff that move slower still require you to take the security patches when they come along.

Having a detailed inventory of underlying dependencies (especially security libraries) for mixed environments will save a lot of trouble when the fire drill bell starts ringing.

The cost of fixing Heartbleed for users of OpenSSL has been many orders of magnitude more than the contributions towards OpenSSL. It was common knowledge that OpenSSL is a mess, but nobody was previously willing to spend the money to improve the situation. It’s easy to be critical of such projects (I’ve been guilty of this myself), but now’s the time to collectively spend some effort and money on doing something.

Static analysis tools don’t always work. It’s fair to assume that everybody in the tools business looks at the OpenSSL code a lot, and they all missed this. It turns out that there’s actually quite a bit of effort involved to make static analysis find Heartbleed.

Many eyes make bugs shallow, but some bugs are very deeply buried, and those many eyes need to be integrated across time. I think ESR is right that Heartbleed does not refute Linus’s Law. There are in fact statistical models out there for how many bugs a given code base will contain, how many of those bugs will be security issues, and what the many eyes discovery rates look like against introduction rates (let’s call that ‘many fat fingers’). Something like Heartbleed was sure to happen eventually, and now it did. There will be more, which is why every defensive position in security needs to be backed up by the ability to respond.

Despite the claims and counter-claims regarding the NSA’s knowledge of Heartbleed I think it’s safe to say that we’d have heard about it via Edward Snowden if it was being actively exploited prior to around a year ago. That said, this is good fuel to the debate on whether intelligence agencies should be using their resources to help with defensive capabilities or using vulnerabilities offensively against their targets.

A closing note about the Internet of Things

There were lots of Monday morning quarterbacks warning that it if it’s hard to patch up software to respond to Heartbleed then it will be almost impossible to patch up the hardware that will form the Internet of Things. A few months back I did an OSHUG presentation on security protocols in constrained environments. I was critical of OpenSSL in that presentation, and it didn’t feature prominently because it’s not tailored to embedded environments.

I suggested at the time that there was an ‘amber’ zone where security can be done, it’s just fiddly to implement. Heartbleed has made me reconsider this – security doesn’t have to just work when the device is made, the security needs to be maintainable. This definitely moves the bar for complexity and implied hardware resources. Maybe not all the way to the ‘green’ zone of comfortable Linux distributions, but a good bit in that direction.

Notes

[1] For a comprehensive explanation of Heartbleed I can highly recommend Troy Hunt’s ‘Everything you need to know about the Heartbleed SSL bug‘. There’s also an XKCD version.

[2] The bug was introduced to OpenSSL in December 2011 and was in the wild since OpenSSL release 1.0.1 on 14th of March 2012. At the time of the announcement the following version history was relevant (from new to old):

1.0.1g NOT vulnerable

1.0.1 through 1.0.1f (inclusive) vulnerable

1.0.0 NOT vulnerable

0.9.8 NOT vulnerable

[3] Our (at the time beta) VNS3 3.5 is based on Ubuntu 12.04, and so it was affected by Heartbleed. The CohesiveFT development team patched the beta version, and the April 30 general availability release is not vulnerable.

This post originally appeared on the CohesiveFT Blog.

Filed under: CohesiveFT, security | Leave a Comment

Tags: Heartbleed, IoT, OpenSSL, security, SSL, tls, vulnerability