Lenovo S206 – first impressions

First the really good news – Lenovo (or more specifically their fulfilment partner Digital River) managed to take an order from me and ship (on time) without some major disaster happening (as I’ve suffered before, repeatedly). They seem to have entirely given up on supplying order tracking information, which is little change in practice to the past system of providing bad order tracking references. At least this time the system worked as it’s supposed to[1].

Why an S206?

My daughter wants a laptop for her upcoming birthday, and when she discovered that there were such things as pink laptops specific colour requirements emerged. I’d have been happy to forgo pink for performance if I’d have been able to get another fast/small/cheap machine like my son’s Lenovo x121e, but I was only recently moaning that such machines pretty much don’t exist. As it became obvious that I’d have to sacrfice some performance to get a small machine (11.6″ screen) at a decent price (~£250) my search narrowed to the HP DM1 and Lenovo S206, which both sport AMD E Series APUs. Since the S206 was available in Pink, and was cheaper I was leaning that way, though I was a little concerned about the performance of the E1200 processor. The deal was sealed by a special offer I stumbled across on the Lenovo web site for the E1800 version with 500GB hard drive at under £250. The PINKMADNESS voucher code that I used seems to have been a short and limited offer to clear down inventory of machines with Windows 7 (32bit).

SSD Upgrade

I was at an event a little while ago where somebody said ‘if you’re not using an SSD in your PC then you’re literally waiting your life away’, and I’ve since switched all of the regularly used household machines over. It took a sacrifice from my dismembered media playing netbook to free up an SSD, but I expect it will get more use this way.

I booted up the installed hard disk for long enough to redeem the £14.99 Windows 8 Pro upgrade offer that’s still on until 31 Jan, then it was time to swap over.

Getting inside the S206 isn’t straightforward – there’s no access hatch like on the X121e. Thankfully Lenovo are open with their hardware maintenance manuals, and with the S206 guide on screen I had good guidance. Getting at the battery, RAM and hard disk involves removing the bottom. Firstly there are a couple of screws under rubber feet, and then the plastic casing needs to be gently eased away from the body of the machine (with a plastic opening tool).

Once I got everything up and running on a fresh Windows 7 x64 install performance was disappointing. Windows Experience Index was reporting 5.6 for disk (no better than the original disk) and SiSoftware Sandra benchmarked a meagre 135MB/s. I checked that the BIOS was set to ACHI (it was), and then upgraded the AMD chipset drivers (having originally used the ones that came on the supplied hard disk). New drivers fixed it, and WEI went up to 7.6 with Sandra clocking 265MB/s.

In use

The chicklet keyboard and screen are pretty much the same as the X121e, which means that this is a nice machine for the money.

There’s just a trackpad, as it’s only ThinkPads that get trackpoints. After using the trackpad on my Chromebook for the past few weeks it was a struggle switching to different gestures, but once I adjusted it’s a decent enough way of getting around.

Subjective speed was initially hampered by the poor I/O performance noted above, but now that’s fixed it feels quick in use. The CPU is the weakest part of the performance story (with a WEI of 3.9), but with the SSD on board and an OK graphics subsytem it will be quick in everyday use (and it’s unlikely to be used for CPU bashing video transcoding).

Conclusion

I expect my daughter will be delighted with this machine, and won’t care very much about a weak CPU. With the SSD on board it should perform well for the applications she’s likely to run on it (browsing, homework, and maybe some casual gaming).

Notes

[1] After writing this post I found an email from Digital River in my spam folder entitled ‘Lenovo UK – Order no. xxxxxxxxxxx – No shipment date’. It continued:

RyanDear Mr/Mrs Swan,

We are contacting you in relation to your recently placed order on the Lenovo Online Store. Unfortunately, the build of the following product you ordered is delayed in manufacturing product name (IdeaPad S206). Although we do not have an estimated ship date, we hope to be able to confirm a ship date in the coming days.

As soon as we have an estimated ship date, you will be notified via email.

We regret any inconvenience this may cause.

The email was dated the day that it arrived, so the machine must have been sent before the email. Clearly Digital River still can’t find their bum with both hands, and I’ll count it as a happy coincidence that the laptop actually shipped within the advertised time. Who knows, I may even be sent another, or get a refund when they tell me that the build is further delayed.

I’m also wondering who ‘Ryan’ is and how that name found its way into the greeting. I guess it’s all part of the Digital River bluehornet.com ‘individualized email experience’.

Update 1 (28 Jan 2013) I just got an email from Digital River saying that my order had shipped – the same order that I received 4 days ago. True to past form the tracking link in the email and on the order status site doesn’t work.

Filed under: review, technology | Leave a Comment

Tags: 11.6", ACHI, AMD, APU, benchmark, driver, E1200, E1800, lenovo, performance, review, S206, ssd, x121e

Scream if you want to go faster

BuyVM, the main hosting service that I use for OpenELEC builds at resources.pichimney.com (and openelec.thestateofme.com), moved servers from San Jose to Las Vegas over the weekend. Whilst the move was happening I temporarily redirected traffic to my secondary VPS to avoid any down time.

I’ve just switched things back to the main server[1], as it has a much larger bandwidth allowance, but I suspect/fear that it’s going to be much slower than before (moving files between the boxes, which is part of the build process, has been about 10x slower). Let me know in comments below if you experience issues downloading image files or release bundles?

One option for speeding things up might be to distribute files using BitTorrent, and I’d be happy to use my servers as seed boxes. Let me know if you’d be interested in trying this (in the comments below)?

Notes

[1] I thought I’d hit publish on this a couple of days ago, but apparently not

Filed under: Raspberry Pi | 2 Comments

Tags: bandwidth, bittorrent, BuyVM, download, hosting, image, openelec, release, SD card, torrent

It got a bit cold

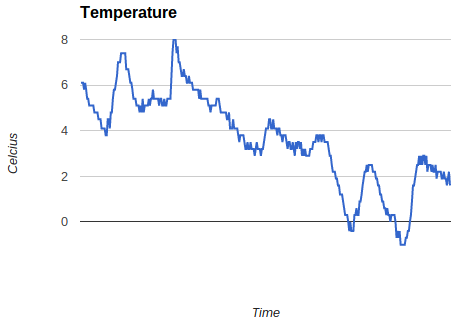

I wrote last week about re-establishing my Nanode based temperature monitoring in anticipation of some cold weather. It came, though it’s not as cold as it was last year (when I was seeing -7.5 being recorded):

It’s clearly warmer in the garage than it is outside, where there is snow lying on the ground. That’s likely to be down to heat from the fridge, freezer and microserver out there. It’s fairly easy to see the day to night ups and downs (even without me putting on an accurate time axis or labels). I was also intrigued to see how much warmer the garage got for a little while when I put my car back in there after a trip out last week (that’s the peak up to 8C). I’m now thinking about adding another sensor outside so that I can compare the temperatures.

Filed under: Arduino | Leave a Comment

Tags: chart, Nanode, temperature

TL;DR

I haven’t got this working (yet). There may even be limitations to the hardware that mean this couldn’t work.

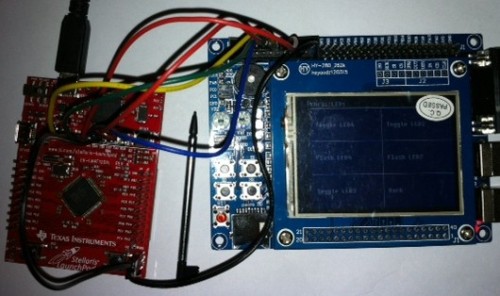

The general idea was to use a cheap ($4.99) Texas Instruments Stellaris Launchpad (LM4F120XL) board in place of a pricier ($34.95) Dangerous Prototypes Bus Blaster. All of the basic pieces seemed to be there – USB connectivity, JTAG breakout.

I’ve got as far as having OpenOCD playing along with the ICDI, but I’ve not yet been able to make it work as a JTAG programmer.

Why?

Last weekend I was following Zizzle’s excellent guide on using cheap Chinese STM32 based boards with touch screens, which I wrote about myself in ‘STM32 Dev the easy way‘. Some of the examples used Bus Blaster, and showed that it was faster, easier and more flexible than programming via the USB/serial port. I don’t have a Bus Blaster, but I do have a couple of Stellaris Launchpad boards.

How

The Stellaris Launchpad has a set of holes onboard that will take header pins to break out JTAG. TI provide a guide on their wiki, (superficially) explaining how these can be used. Sadly it’s not entirely clear whether JTAG support is generic, or limited to other TI devices. I hooked up the boards like this:

OpenOCD

OpenOCD

Zizzle’s examples with the Bus Blaster used Open On-Chip Debugger (OpenOCD) as the software plumbing. Support for TI’s In Circuit Debugging Interface (ICDI) wasn’t present in the version bundled in the VM I was using, but is available in more recent dev builds. I cloned the project from git and set about putting in place the dependencies that I needed to make a new version with ICDI support enabled. This blog post from Scompo traces out similar steps to the ones I took if you’re interested in the detail.

Once OpenOCD was correctly built, and I had the right udev settings to allow use of the USB device without sudo I was able to connect to the Launchpad. The next stage was to modify Zizzle’s config files to use the TI board rather than Bus Blaster:

OpenOCD config

Zizzle starts OpenOCD with the command line ‘openocd -f jtag/stm_board.cfg’, and the stm_board.cfg looks like this:

telnet_port 4444 gdb_port 3333 gdb_memory_map enable gdb_flash_program enable source [find jtag/busblaster.cfg] source [find target/stm32f1x.cfg]

The busblaster.cfg looks like this:

interface ft2232 ft2232_device_desc "Dual RS232-HS" ft2232_layout jtagkey ft2232_vid_pid 0x0403 0x6010

and I found a corresponding file for the Launchpad that looks like this:

interface hla hla_layout ti-icdi hla_vid_pid 0x1cbe 0x00fd # unused but set to disable warnings adapter_khz 1000

So with a change to the second to last line to reference the ti-icdi.cfg rather than the busblaster.cfg I was all set. Sadly this is what I see when I try to start things up:

Open On-Chip Debugger 0.7.0-dev-00135-g76afade (2013-01-13-08:03)

Licensed under GNU GPL v2

For bug reports, read

http://openocd.sourceforge.net/doc/doxygen/bugs.html

adapter speed: 1000 kHz

adapter speed: 1000 kHz

adapter_nsrst_delay: 100

Runtime Error: target/stm32f1x.cfg:27: invalid command name

"jtag_ntrst_delay" in procedure 'script'

at file "embedded:startup.tcl", line 58

at file "jtag/stm_board.cfg", line 8

at file "target/stm32f1x.cfg", line 27

and that’s where I’m presently stuck :(

Conclusion

It would be very nice if the Stellaris Launchpad could be used as a generic JTAG programmer, and all of the pieces seem to be available, they’re just not quite moving together for me yet. It’s quite possible that TI have locked things down so that it isn’t actually possible, which would perhaps be a bit mean of them, but might explain why I’m not just following the steps of somebody more knowledgeable’s howto. I’ll write updates if anything changes.

Filed under: making | 5 Comments

Tags: Bus Blaster, dev board, ICDI, JTAG, launchpad, LM4F120XL, OpenOCD, programmer, Stellaris, STM32, ti

Chromebook – a week on the road

I spent the past week as exec in residence for the London Fintech Innovation Lab, working with the 7 winning startups based in the shiny new Level 39 Technology Accelerator at Canary Wharf. It seemed like the perfect chance to try out my Chromebook in a more work oriented setting.

Battery life

I was brave, and decided not to take the power supply with me. I wouldn’t be using my Chromebook all the time, so I thought 6.5 hours would be enough to get me through each day. It was. I wasn’t even running for the power supply when I got home as there was always enough juice left for any sofa surfing that I wanted to do.

Google Docs Only

I encountered one hiccup where an old Word document I imported didn’t format correctly, and rather than spending ages reformatting it I waited until I was home to sort it out on my PC. At a push I could have used remote desktop, but it wasn’t that urgent.

I’ve pretty much switched over to Google Docs from MS Office anyway, so the Chromebook worked fine with all of my ongoing stuff.

OpenVPN

The launch of the iOS client for OpenVPN spurred me on to get it working with the Chromebook. It’s fine if I run it from the command line in a dev mode crosh shell e.g.:

sudo openvpn my_vps.ovpn

I have still utterly failed to get things working with the regular (non dev) approach using .onc files and importing private keys etc., but I’m not feeling too bad about that, as there’s a post in one of the support groups from a member of the OpenVPN team saying ‘the interface for OpenVPN in Chrome OS seems to be pretty much unusable for your average user‘. Basically Google need to provide a tool to parse .ovpn into .onc, and some better howto guides would be nice too.

Telephony

I’ve been using Google Voice for some time, and presently have things set up so that my mobile phone and Skype In get routed there (which would be easy if I was in the US, but takes a bit of SIP Sorcery from the UK). In the past I’ve not made much use of the gmail chat functionality for voice calls, but I gave it a try this week and it works well. I was almost tempted to buy some credit so that I can call none US numbers, and then I realised that I could use my US Skype ToGo number, which gives me free calling to the UK via a Skype subscription and Skype pay as you go rates for any other number I might call. Of course it would be great if there was a Skype app for ChromeOS, or if Google Voice was rolled out to the UK, but I won’t be holding my breath on either of those things.

ChrUbuntu

I haven’t needed it. ChromeOS has been sufficient.

Conclusion

Google Apps got me through the week pretty much fine from a software point of view, and the Chromebook stood up well from a hardware perspective. It was great to be liberated from a power cord AND have a decent keyboard. I didn’t feel like I was compromising using a cheap machine (and I’m pretty sure most of the people stopping by for a chat probably mistook it for an 11″ Macbook Air).

Filed under: review, technology | 1 Comment

Tags: battery, Chromebook, Chrubuntu, OpenVPN, telephony, Voice, voip

STM32 dev the easy way

A while ago I bought an STM32 dev board from China on eBay, as it seemed to have so much more than the official Discovery boards coming with:

- A 2.4″ LCD with touch screen input

- 4 Pushbuttons (and a Reset button)

- 4 LEDs

- 2 Variable resistors

- A Micro SD slot

- A buzzer

- RS232

- 2 USB sockets

- JTAG

- A whole bunch of GPIO pins

In sum a whole bunch of awesome stuff. Sadly sometimes when things look too good to be true they are. After waiting ages for it to arrive I discovered that most of the documentation was in Chinese. It ran a pretty little demo app, but I didn’t know where to start with programming it. I put it on the shelf in the hope that one day something would show up to help, though realistically I expect it to gather dust – maybe I’d have a go at using the LCD for another project.

Zizzle to the rescue

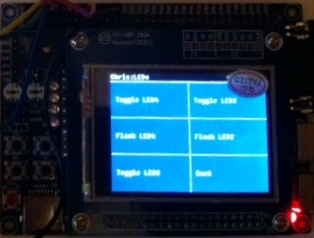

At the end of October I saw a piece on the Dangerous Prototypes blog ‘Tutorial: STM32 boards and TFT LCD touchscreens‘, which linked back to Zizzle’s ‘STM32 LCD touch screen demo‘. I downloaded the VirtualBox image containing the tools and sample code, but didn’t do anything with it as I didn’t feel like I had the time. I shouldn’t have worried; when I finally got around to trying it yesterday I was up and running in minutes – watching the YouTube guides and clicking along in my own virtual machine. Another few minutes and I had customised menus on the touch screen:

It was also pretty straightforward to get debug messages from printf into a console.

I then went on to waste hours trying to get a TI Stellaris LaunchPad to work as a JTAG programmer in place of the BusBlaster that Zizzle had used, but that’s another story.

Why this works

Setting up tool chains for embedded devlopment is fiddly, but virtual machines make a great container for all of that effort. I’m now starting to wish that I’d had a go using a Linux VM for Andrei’s ‘STM32F3 Discovery + Eclipse + OpenOCD‘, but I thought it would be much harder to get USB devices working in the VM than it turned out to be (NB Andrei has since done a Windows version of his instructions).

Conclusion

Putting a complete tool chain in a VM image makes it super easy to get going with a dev board, especially when accompanied with good quality videos explaining how things work. Thanks Zizzle :)

Filed under: making | Leave a Comment

Tags: ebay, LCD, STM32, touch screen, VirtualBox, VM

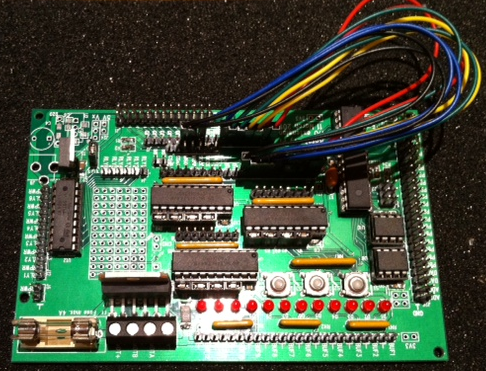

In earlier posts of this series I’ve looked at ladder board and Quick2Wire’s boards. This post is about the official expansion project board for the Raspberry Pi, named after its creator Gert van Loo, the Gertboard.

Construction

Construction

Like the other boards I’ve looked at Gertboard comes as a kit of parts. The two things that are unlike the other boards are that there are a *lot* of parts in the kit, and some of them are surface mount components.

Soldering SMT

Surface Mount Technology is designed for machines not people, and in most cases kits aimed at hobbyists come with any SMT bits already in place. Not the Gertboard though. It is possible to solder SMT by hand, at least with simple components like resistors and capacitors, it’s just a bit tricky. If you’re thinking of building a Gertboard then I have two pieces of advice for you :

- Don’t work over a carpet.

- Clean the floor before you start, because at some stage you’ll be looking for a capacitor the size of a bread crumb, and you don’t want to be dealing with actual bread crumbs.

My daughter’s young eyes and hands turned out to be very helpful, but even with that assistance we had a few cases of hunt the component after something had pinged out of the needle nose tweezers I was using to hold things in place.

Soldering the rest

The through pin parts of the Gertboard are as easy as any of the other boards I’ve worked with. There’s just a lot of them, so reckon on an entire afternoon to put the whole thing together.

Capabilities

Gertboard does a lot of different things (and has to be configured with various jumpers and jump leads for whatever pieces of functionality you’re after). It has buttons, LEDs, ADCs, DACs, motor controllers and more. It even has its own computer – the same Microcontroller (ATmega328) as used on many Arduino boards.

There’s a lot more functionality than I can really do justice to here, so I’d suggest a read of TechFruits’ ‘Getting to Know Your Gertboard’.

In use

I’ve not really done much with my Gertboard yet past running some rudimentary GPIO examples that use the push buttons and LEDs – stuff that would work just as well on the ladder board. So far its enormous potential has exceeded my ability to think up any cool projects for it. As the motor controller is something that I don’t have with other Raspberry Pi boards (or any of the other dev boards I use) then that’s the most likely area I’ll exploit.

Conclusion

Gertboard is the mother of all project boards for the Raspberry Pi. Just putting it together feels like a major accomplishment. I look forward to having the time and a bright idea for doing something really cool with it.

Filed under: Raspberry Pi, review | Leave a Comment

Tags: ADC, DAC, dev board, Gertboard, GPIO, Raspberry Pi, Raspi, RPi, SMT, soldering, surface mount

End of support, end of the line

I’ve written before about the myth of software support. Software mostly doesn’t work, vendors mostly don’t fix stuff, and the world keeps turning anyway. Everything’s broken and nobody’s upset.

So why do companies stop using perfectly good stuff (hardware and software) simply because they can’t buy support from the original vendor? This position seems nonsensical to me, but I’ve come across two examples in the past week:

IRIS

The Iris Recognition Immigration System (IRIS) was a perfect example of trading privacy for convenience. I let the UK government take pictures of my eyes, and in return they let me get out of passport control quicker by going through an automated gate rather than standing in line. You didn’t have to be a UK Citizen to use it, so it was particularly beneficial to frequent travellers from outside of the EU who might otherwise face a long line at passport control.

One of my friends complained the other day about IRIS not being available, and quickly got an answer from another friend about the reason:

The machines are still there. I’d bet that the machines still work. But somebody is too scared to turn them on in case they break because Microsoft won’t any longer be on the hook to ‘support’ them. I can make two obvious points at this stage:

- The appropriate time to stop using the machines is when they actually stop working.

- If they had stopped working when the ‘support’ was still in place then it would still have taken days (at least) to get a fix.

What is it about software support that causes such insane risk/benefit trade offs?

Part of the problem is of course ‘security’. Microsoft ending support for XP means no more patches for vulnerabilties. This is a problem if you’re an Internet connected PC surfing the web. This shouldn’t be an issue for an applicance with some embedded software.

I’m left wondering how much the UK Borders Agency paid MS for support for IRIS, and how much utility they ever got out of that contract? I expect the answer is something along the lines of too much and not enough.

Before moving on it’s worth noting that IRIS has been partially replaced by new automated gates for those with EU issued RFID enabled passports. This is no good to Kirk, because he has a US passport, and it’s turning out to be no good to me because the regular travelling public has a much higher moron that can’t work things ratio than those that opted into IRIS.

Update (26 Jan 2013) – Kirk tweeted yesterday evening that the IRIS machines are back in action (at least at Heathrow T5). Perhaps somebody saw sense.

Pano Logic

The next example I’ve come across is Pano Logic, who made a thin client device (which they branded ‘Zero Client’). It seems that at least one of their customers has decided to trash over a hundred of the devices as their IT support guy is now looking for creative ways to hack the hardware.

Presumably the day before support ended the devices were working fine, and the day after they were still working fine. The lack of support shouldn’t be an issue until something actually goes wrong. The main causes of going wrong are installation issues (which had already been passed) and age issues (when component failure comes along) – hence the bathtub curve. The age end of the bathtub isn’t all that often an issue in IT because we tend to replace stuff long before it falls apart, though the Pano Logic device might have been an exception – I’d expect that obsolesence would catch up with them due to changes in monitor technology or something like that.

Conclusion

The ability of IT vendors to support things is poor at the best of times. Withdrawal of support shouldn’t be an immidiate trigger to get rid of something – it’s just one of the indicators that it’s time to draw up plan B for when failure actually does occur.

Filed under: could_do_better, technology, travel | 2 Comments

Tags: end of life, IRIS, Pano Logic, support

Return of the Nanode thermometer

It’s almost a year since I built my Nanode thermometer, and it looks like another really cold snap is headed towards the UK – perhaps snow over the weekend.

I’ve not had it set up for a little while, as the TMP36 sensor was reclaimed for a project that put Scratch and an Arduino together to create an on screen fire breathing dragon when hot breath hit the sensor. I’ve also more recently used the sensor with the Quick2Wire Analogue board.

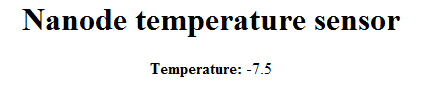

This time I wanted to record data from the Nanode so that I could do some charts later on. I could have done this by modifying the sketch to use MQTT or post data to Pachube Cosm or similar, but I took the path of least resistance and wrote a couple of scripts to scrape from the existing app:

get_temp.sh uses lynx and some sed to strip the temperature reading from the cruft around it:

lynx -nonumbers -dump http://nanode.swos.local | grep Temperature | sed s/'Temperature: '// | sed -e 's/^[ \t]*//'

loop.sh prints a formatted date and time to a (CSV) text file followed by the temperature from get_temp.sh:

#!/bin/bash while : do printf %s "$(date '+%Y%m%d%H%M')" >> temp && echo -n ',' >> temp && ./get_temp.sh >> temp sleep 1800 done

I’m running loop.sh in a screen so that I don’t need a persistent connection to the VM. I’ll update with charts if any of them turn out to be interesting (e.g. a steep overnight drop or something like that).

Filed under: Arduino, code | Leave a Comment

Tags: arduino, bash, csv, date, lynx, Nanode, network, printf, script, sed, sensor, temperature, thermometer

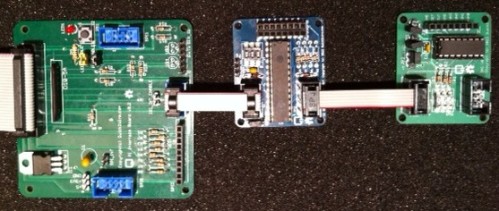

In part 1 of this series I looked at ladder board, and in the next part I plan to review the Gertboard. This post is about Quick2Wire‘s boards, where I’ve been fortunate enough to try out some alpha and beta samples.

Quick2Wire concept

There’s an interface board that connects to the general purpose input output (GPIO) headers on the Raspberry Pi, which can be used on its own as a safer way to break out the GPIO pins (versus something like a Pi Cobbler).

There are also extension boards that plug into the I2C bus (and more planned that will harness SPI). I tried out two of the I2C boards, which can be daisy chained together.

Interface Board

It took my son around an hour to turn this from a kit into a working board, and I didn’t have any faults to resolve. It offers a bunch of different functionality:

- 8 diode protected GPIO ports

- a push button and LED that can optionally be connected to two of the GPIO ports

- a voltage regulator for extra 3.3v

- an FTDI header for serial I/O

- I2C connection

- 2x SPI connectors

My first test for the board was to try out the push button and LED using Gordon Henderson’s Wiring Pi from the command line, and I was quickly able to read whether the switch was pushed and turn the LED on and off.

I returned to the LED later when using Quick2Wire’s Python API. Firstly I installed their GPIO admin command which lets an ordinary user do stuff with GPIO without using sudo. There are a few steps to getting this going:

- Add Quick2Wire as a Raspbian Software Source

- Install with:

sudo apt-get install quick2wire-gpio-admin

- Add your user to the gpio group

sudo adduser $USER gpio

- Log out and back in again so that the group change can take effect

- The gpio-admin command is now ready to use e.g. to allow the LED to flash:

gpio-admin export 12

The Python API is installed from github (I put it into my home directory):

git clone http://github.com/quick2wire/quick2wire-python-api

I created a little environment script (env.sh) to set up PYTHONPATH in accordance with the installation instructions:

export QUICK2WIRE_API_HOME=/home/pi/quick2wire-python-api export PYTHONPATH=$PYTHONPATH:$QUICK2WIRE_API_HOME/src

Then when I wanted to use the Python API I could simply:

. ./env.sh

I then modified one of the Quick2Wire examples a tiny bit to give me an executable script:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from time import sleep

from quick2wire.gpio import Pin, exported

with exported(Pin(12, Pin.Out)) as pin:

while True:

pin.value = 1 - pin.value

sleep(1)

I2C Extender

The I2C extender board offers a further 16 digitial GPIO pins, and took my daughter about an hour to put together[1]. To use the board requires I2C support to be enabled on the Raspberry Pi (and as previously noted this can interfere with other GPIO stuff that uses the pins that are shared with I2C).

/etc/modprobe.d/raspi-blacklist.conf needs to look like this:

# blacklist spi-bcm2708 # blacklist i2c-bcm2708

and i2c-dev needs to be added to /etc/modules:

# /etc/modules: kernel modules to load at boot time. snd-bcm2835 i2c-dev

If there are other modules there too (such as 8192cu for WiFi) then that’s not a problem.

Just like with GPIO it’s necessary to add the user to the appropriate security group:

sudo adduser $USER i2c

At this stage a reboot is needed (rather than just log off and back on again) so that the kernel module changes can take effect.

Once the RPi is back up and running it’s possible to see the i2c devices with i2cdetect:

i2cdetect 0

WARNING! This program can confuse your I2C bus,

cause data loss and worse!

I will probe file /dev/i2c-0.

I will probe address range 0x03-0x77.

Continue? [Y/n]

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f

00: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

10: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

20: -- -- 22 -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

30: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

40: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- 48 -- -- -- -- -- -- --

50: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

60: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

70: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

The example above shows that the expander board is connected at address 22 (because I fiddled with the address dip switches) and the analogue board is at 48.

I didn’t really do much with the expander board yet, but I did modify one of the Python examples to prove to myself that it would work:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import quick2wire.i2c as i2c

address = 0x22

iodir_register = 0x00

gpio_register = 0x09

with i2c.I2CMaster() as bus:

bus.transaction(

i2c.writing_bytes(address, iodir_register, 0xFF))

read_results = bus.transaction(

i2c.writing_bytes(address, gpio_register),

i2c.reading(address, 1))

gpio_state = read_results[0][0]

print("%02x" % gpio_state)

Analogue board

The analogue board is based on the PCF8591 IC, which offers 4 8bit analogue to digital inputs and a single 8bit digital to analogue output. Once again it took about an hour for my daughter to put it together[2].

I tried it out with a TMP36 temperature sensor connected to AIN0 and the following code to read out the temperature in celcius every second:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from time import sleep

from contextlib import closing

import quick2wire.i2c as i2c

from quick2wire.parts.pcf8591 import PCF8591

with closing(i2c.I2CMaster()) as master:

pcf = PCF8591(master)

pin = pcf.begin_analogue_read(0)

while(True):

print(int(((330*pin.read())/256)-50))

sleep(1)

Conclusion

The Quick2Wire boards bring together a modular and extensible hardware platform with a rich and easy to access software platform. I’m looking forward to getting a better understanding of the Python API so that I can do more with the boards I do have, and there’s plenty of scope for adding more boards later. It will be interesting to see what comes along to use the SPI interfaces.

Notes

1. I had some trouble initially with the expander board not showing up on i2cdetect, which came down to a very hard to spot dry joint on the board.

2. Somehow my daughter managed to get a solder splash on the component side of the board that shorted AGND and VREF. This was a total pain to diagnose and fix as I had to remove the chip holder to resolve the issue.

Filed under: code, howto, Raspberry Pi, review | 2 Comments

Tags: ADC, API, DAC, dev board, github, GPIO, I2C, PCF8591, python, Quick2Wire, Raspberry Pi, Raspi, RPi, soldering, Wiring Pi