MS improve Azure free trial

I was very frustrated last month when my trial subscription of Azure IaaS was disabled after a couple of days use (and I’m working on a post detailing how I later resurrected my server). The cause of that issue was that the free trial only bundled 1m IOPS (storage transactions).

I’ve been watching my use of the service this month, and waiting for the meter to start ticking up, but that hasn’t happened yet as the IOPS limit is now a much more generous and realistic 50x larger:

It’s great to see that Microsoft have made the trial more useful.

It’s great to see that Microsoft have made the trial more useful.

Filed under: cloud, did_do_better | Leave a Comment

Tags: Azure, Microsoft, MS

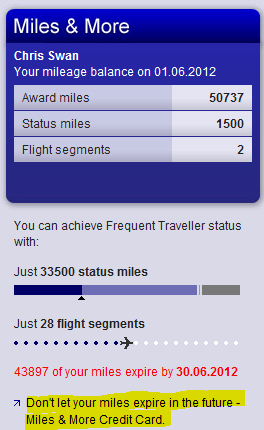

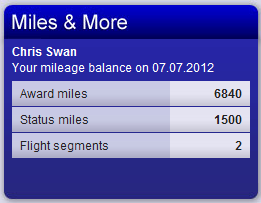

I fly to Zurich a few times a year, and often fly with Swiss, so I’ve been a member of their Miles & More rewards programme (which is run by Lufthansa) for some time. To help keep hold of my miles (and even top them up a little) I got the connected credit card from MBNA. Each month I get an email that looks like this:

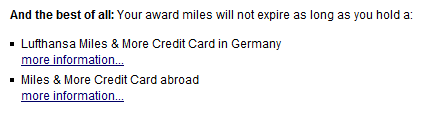

I foolishly thought that because I had the card my miles were safe (and perhaps didn’t notice or pay attention to the red expiry warning when it came along). Of course the marketing message:

I foolishly thought that because I had the card my miles were safe (and perhaps didn’t notice or pay attention to the red expiry warning when it came along). Of course the marketing message:

is different from the smallprint:

So over the past month my mileage balance has been pretty much vaporised:

So it looks like I have little incentive to do business with Swiss or MBNA any more (and I miss out on that ski trip in the Swiss alps that I thought I might one day use those miles on).

So it looks like I have little incentive to do business with Swiss or MBNA any more (and I miss out on that ski trip in the Swiss alps that I thought I might one day use those miles on).

It’s just a shame it wasn’t made clear to me that my credit card wasn’t shielding me from expiry. I’d have given the miles to charity or something rather than have them just expire.

Filed under: could_do_better, grumble, travel | 3 Comments

Tags: expired, expiry, Lufthansa, MBNA, mileage, Miles and More, rewards, Swiss

I’ve had my original Samsung Galaxy Tab for over a year now, and it’s a great device. I particularly like that it has 3G (and that it came with a SIM that I can use relatively inexpensively in the US[1]). It shipped with Android 2.2 (Froyo), and after rooting and restocking I’ve pretty much left it alone as the Android 2.3 (Gingerbread) version of CyanogenMod that I run on my ZTE Blade never officially supported the Tab. I noticed the other day though that the Tab is now supported for the Android 4.0 (Ice Cream Sandwich) version of CyanogenMod (CM9).

Installation

Unfortunately the upgrade instructions assume that you’re already on Android 2.3, which I wasn’t, and after copying over the suggested kernel I found that I had an unbootable device:( I fixed this up by running through the restocking and upgrade process for Overcome, and then used the Overcome recovery to install CM9 and Google Apps.

In use

It’s like having a new tablet – faster, better looking and more robust. The only drawback seems to be that battery life might not be what it used to be (or maybe I’m just using it even more now). It would also be nice if I could get rid of the soft keys (since the Tab has hard keys), but that’s a minor annoyance. The newer Swype is awesome too.

Conclusion

Better tablets have come along since the original Galaxy Tab, but it’s still a great piece of hardware, and CM9 gives it a fresh lease of life. My fingers are crossed that they’ll port Android 4.1 (JellyBean) over to it too.

[1] In the UK I have a Three SIM that came with a MiFi and gives me 15GB data/month (always more than enough). When I travel to the US I use AT&T’s tablet plan to get 3GB for $30 that lasts a month.

Filed under: technology | Leave a Comment

Tags: 4.0, android, boot, bricked, CM9, CyanogenMod, Galaxy, Ice Cream Sandwich, ICS, Overcome, recovery, Samsung, tab, unbootable, upgrade

Drones

Barely a week goes by these days without me seeing something about a cool home built drone project on sites like Hack a Day, and a couple of weeks ago the Open Source Hardware Users Group (OSHUG) had a meeting dedicated to drones. I really liked the idea of using Kinect as a controller for an ARDrone:

Sadly the chaps from OpenRelief weren’t able to make the meeting, but they sent along an excellent video of what they’re up to that more than made up for things (and means that you can see as much as I did of the great work they’re doing):

I can see loads of potential for these things as kids and hacker toys, and the possibilities with mesh networks and the Internet of Things is enormous. Unfortunately there’s a down side… Drones have been an effective tool in the ‘war on terror’ for some time, but the tables could turn as the forces of consumerisation turns them from the asymmetric weapon of 1st world governments into the asymmetric weapon of anybody. The first time I read of this concept was in Scott Adam’s ‘The Religion War‘, but I’m told that there are earlier SF references such as David’s Sling by Mark Stiegler. The overreactions by law enforcement have already started, which prompted me to talk about the topic at the recent London CloudCamp ‘Independence Day Special’:

I concluded by saying that we need to start the debate on policy now – before something that causes a knee jerk reaction happens.

Filed under: politics, technology | 1 Comment

Tags: ARDrone, drone, drones, kinect, OpenRelief, OSHUG, quadcopter

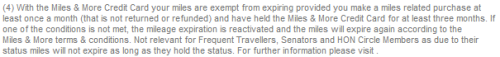

In part 1 I went through setting up an SSH tunnel, and waking up machines on the home network. In this part I’ll run through how to use various protocols and clients to connect to machines on the home network.

SSH tunnels on PuTTY

SSH lets you tunnel many other protocols through it (using a technique known as port forwarding), and PuTTY has a sub menu for configuring this:

Here I’m illustrating tunnels for VNC (to the RPi itself), RDP (to a Windows PC), HTTP (for a NAS or anything else with a web console) and SOCKS (to route web traffic through your home network).

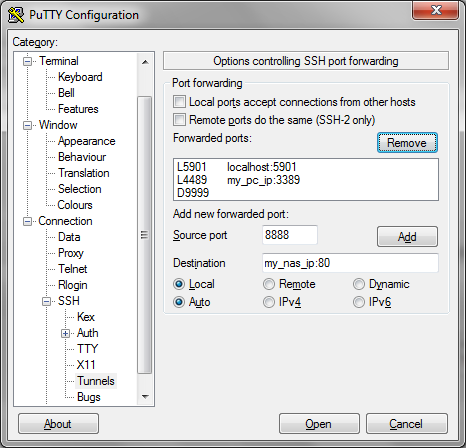

VNC

I touched upon VNC in my guide to using the Raspberry Pi on the iPad, and there’s a more general guide on Designspark. Assuming that you have things working on your home network all that you need to change when using an SSH tunnel is to connect to localhost rather than the IP or name of the RPi itself (NB if you’re running VNC on the machine you’re connecting from then you’ll have to use an alternate port):

RDP

The Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) was originally used for multi user computing from Windows Servers. Later it was made available for remote admin of servers, and since Windows XP it’s been available on desktops. It’s switched off by default, so the first thing needed is to enable it on the machine you want to connect to remotely (Right click on [My] Computer in the start menu and select properties then Remote Settings):

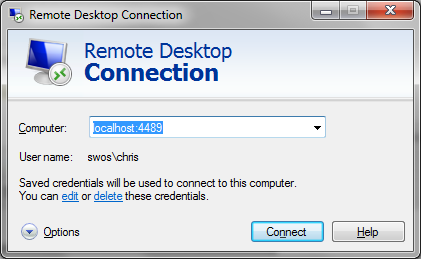

Since you might have RDP enabled on the machine you’re connecting from I’ve chosen to use a different port (4489) rather than the default (3389). To connect run ‘mstsc’:

Web interfaces

Many devices on the home network can be accessed through a browser, and if you set up a tunnel as illustrated above all that’s needed is to browse to localhost:port (though be careful with proxy configuration if you’re using a proxy or if you tunnel web traffic as described below).

Web traffic

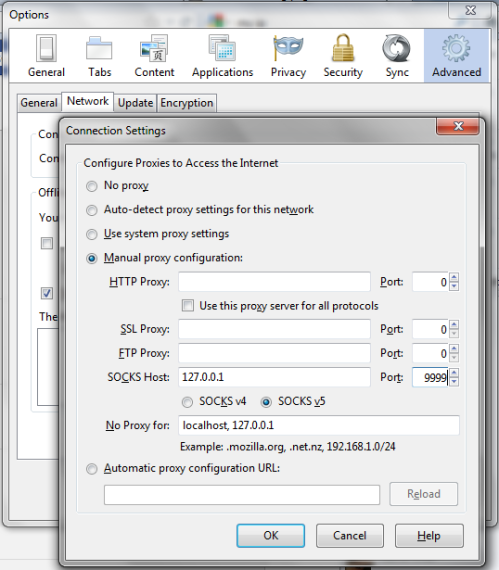

There are times when you might want to appear to the Internet as coming from your home network rather than whatever network you’re on. You can tunnel your web traffic through the Raspberry Pi by using a Dynamic port (also illustrated above) as a SOCKS proxy e.g. with FireFox:

Anything else

Pretty much any protocol can be sent down an SSH tunnel, including SSH itself (so you can run tunnels through tunnels if you like). The only limits are your patience and ingenuity.

Before leaving

It’s one thing to wake machines up remotely, but it’s not always obvious how to send them back to sleep/hibernate – the right options don’t appear in the start menu. The rick is to click on the menu bar (usually at the bottom of the screen) then hit Alt-F4, which will then bring up a menu that includes sleep and hibernate (if they’re enabled).

Conclusion

In this two parter I’ve covered setting up SSH to your Raspberry Pi at home then using it to wake up other machines on the network. I’ve then run through how to tunnel various remote access protocols through SSH so that you can take control of machines remotely.

Filed under: howto, Raspberry Pi, security | Leave a Comment

Tags: howto, http, Putty, Raspberry Pi, Raspi, RDP, remote access, router, RPi, SOCKS, SSH, tunnel, VNC, vpn, wakeonlan

In this post I’m going to cover setting up a network tunnel and waking up other computers on the home network.

Why use a Raspberry Pi?

A tunnel needs two ends, so at home this means leaving at least one machine switched on – keeping the electricity meter turning. One of the great things about the Raspberry Pi is its low power consumption. At 3.5W it will cost less than £3 to leave it on all year.

Overview

There are numerous types of virtual private network (VPN) using a variety of protocols such as IPSEC, L2TP, PPTP and SSL. Most home broadband routers support one flavour of these, but can be very fiddly to configure (both on the router and the client). This howto will cover use of secure shell (SSH). When two computers are connected using SSH it’s possible to tunnel a variety of other connections through that tunnel, allowing all sorts of things to be accomplished.

SSH server config

I’ll assume you’re using the Debian “squeeze” build, though these instructions should be similar for other distributions.

The OpenSSH server is included in the build, but not set to start by default. To fix that:

sudo mv /boot/boot_enable_ssh.rc /boot/boot.rc

Then reboot.

Keys please

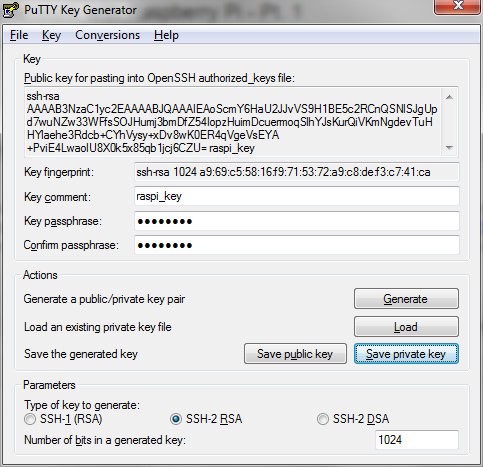

It’s possible to use SSH with a username and password, but this approach is susceptible to password sniffing and brute force attacks[1]. It’s more secure to use SSH keys. I’m going to use the PuTTY client later, so I’ll use its companion key generation tool PuTTYgen. When you launch the tool it will ask you to wiggle the mouse to generate randomness, and once that’s done it’s time to name the keys:

Save the private key somewhere safe. You’ll need it later on the machine that you want to connect from remotely.

The public key needs to go into ~/.ssh/authorized_keys on the Raspberry Pi:

cd ~ mkdir .ssh chmod 700 .ssh echo [paste public key text here] >> .ssh/authorized_keys chmod 600 .ssh/authorized_keys

Port forwarding – home router

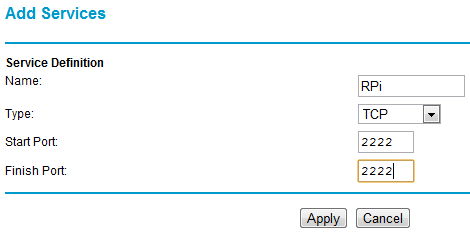

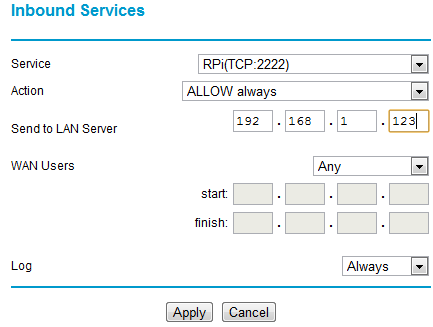

To get to your RPi remotely requires a network port to be forwarded from the home router to the Pi. Details of configuring this vary from one router type to another. The illustrations that follow are for a Netgear DG834. With this particular router the first step is to configure a service:

I’ve used port 2222 (SSH usually runs on port 22, but I’m using something different as its less likely to be found by the multitude of bots out there prodding our ports). Any port between 1024 and 65535 should be OK – pick something that’s easy for you to remember. The next step with my router is to configure the firewall to use the service:

What this is doing is forwarding all incoming traffic on port 2222 to the IP address of the RPi (example here is 192.168.1.123).

Once the forwarding is set up add the port into the SSH daemon config on the RPi and restart SSH:

sudo sh -c "echo 'Port 2222' >> /etc/ssh/sshd_config" sudo service ssh restart

Connecting remotely

All the pieces are in place now for you to connect remotely. The easiest way to try this will be with a machine connected to a MiFi or smartphone with hotspot mode (or use a friendly neighbour’s WiFi) – if there is troubleshooting to be done then you don’t wanting to be running backwards and forwards to your friendly local coffee shop (unless the coffee is REALLY good).

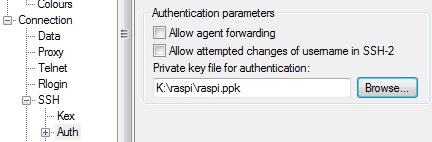

First configure PuTTY (or the SSH client you’re using) to use the private key you made earlier:

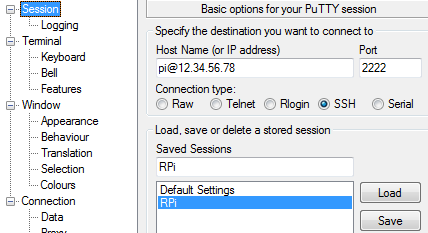

Next configure a session with the right IP address (google for ‘my ip’ when at home) and port, then save it for reuse later:

All being well you can now connect.

Waking up another machine

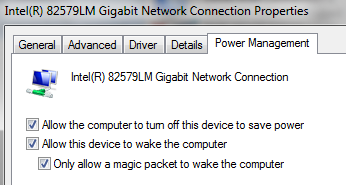

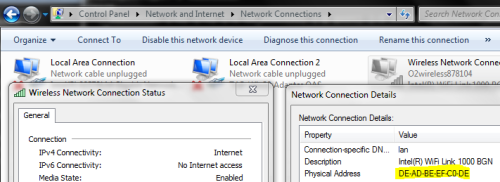

The Debian squeeze build for the wakeonlan tool, but for it to work you need to have the machine configured to wake up and know its hardware (MAC) address. Wake on LAN is configured in the control panel for network adaptors in the Configure panel for a given adaptor’s properties:

The MAC address can be found using ‘ipconfig /all‘ from the command line, or in the status panel for a live network connection.

I could now wake up the machine illustrated above using this command from the RPi:

wakeonlan DEADBEEFC0DE

It’s hard to remember MAC addresses, so it’s probably best to put that line into a little wake_machine.sh script that can be run in the future.

Conclusion

The part has covered setting up SSH and waking up a machine remotely. In the next part I’ll go through how to configure SSH tunnels to access machines remotely (including the Raspberry Pi desktop) and web services on your home network.

Filed under: howto, Raspberry Pi, security | 9 Comments

Tags: howto, Putty, Raspberry Pi, Raspi, remote access, router, RPi, SSH, tunnel, vpn, wakeonlan

Azure account disabled

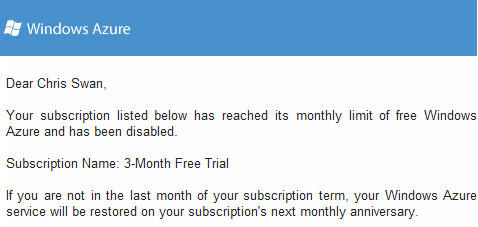

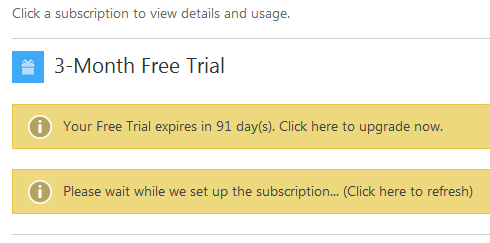

After just 2.5 days of my 90 day trial my Azure account has been disabled:

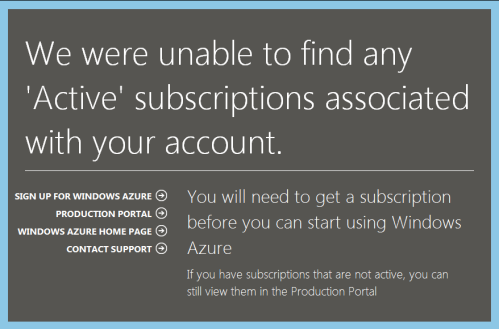

I *think* this has happened because I’ve exhausted the (paltry[1]) 20GB bandwidth allocation that comes with the trial, and that this happened because people were downloading OpenELEC builds/images from the web server I stood up in part 2 of my howto. I have no way of knowing for sure, as this is what I see when I log in to my account:

I was hoping that the portal would let me see some summary of the resources I’d consumed, but instead I’m completely locked out.

Lesson for me

I knew that there was a risk of people downloading stuff from the web server. I should have put up a redirect page to the VPS where I have been hosting builds and images.

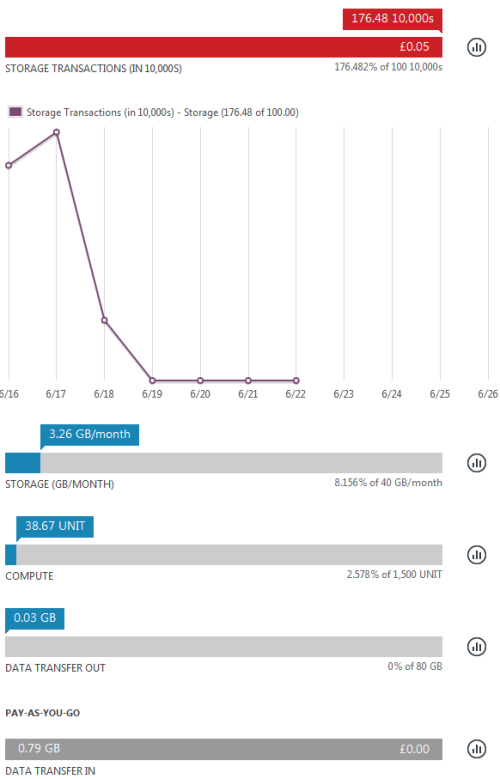

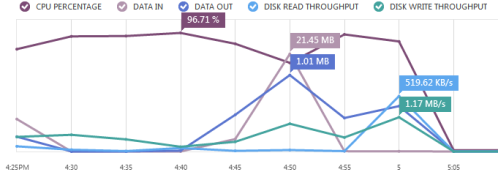

Update (22 Jun 2012) – Thanks to Nils for pointing out that usage metrics are in fact available in the portal. After a bit of poking around I was able to see this:

This is worse than I thought, as it shows that I hit an I/O limitation rather than a bandwidth cap, which means that anybody following my howto will be caught in the same trap. My only conclusion here is that the Azure trial (and possibly the IaaS offering as a whole) is useless for anybody doing I/O intensive work (like compiling something). I’d also point out that most other IaaS offerings don’t have similar limits/charges for I/O.

The I/O allowance in the free trial bundle also seems excessively mean. The pricing for a month of a small Linux instance is $57.60, and the pricing for 1M I/Os is 10c – MS should probably be offering a better balance here. If the allowance was 10M (or $1.00 worth) then I reckon I’d have got at least halfway through the month before hitting it.

Lessons for MS

- Make it easier for people see what resources they’ve used.

- Have soft limits and warn people when they’re approaching them (e.g. if I used all my bandwidth in 2.5 days then it would have been nice to be told after 1.25 days that I’d already burned 50%, and again when I hit 80% etc.)

- Be clear about pricing for usage outside of the trial allowance. I don’t know right now if I could get back up by paying for a little bandwidth, or if I’d have to pick up the tab for the VM and its storage too?

Notes

[1] A typical small VPS (e.g. Linode) comes with 200GB of transfer per month, so it seems MS is being particularly stingy here.

Filed under: cloud, could_do_better | 5 Comments

Tags: alerts, Azure, bandwidth, disabled, limits, Microsoft, monitoring, MS, trial

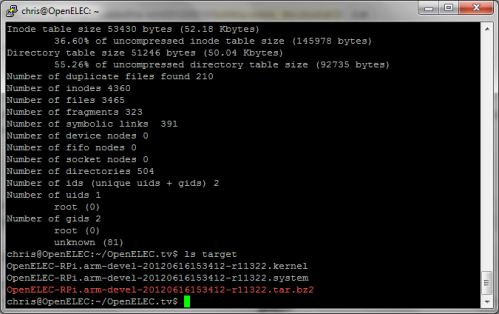

In the first part of this howto I went through signing up for a cloud service, provisioning a VM, installing the build tools and kicking off a build. All being well you should end up with something like this:

Azure can also give you a pretty chart of how busy the VM was during the build process:

Unpacking the release

First create a directory:

mkdir releases

and then unpack the build:

cd releases tar -xvf ../target/OpenELEC-RPi.arm-devel-timestamp-release.tar.bz2

Important note: above I’ve used OpenELEC-RPi.arm-devel-timestamp-release as a generic label for something like OpenELEC-RPi.arm-devel-20120616153412-r11322. Please substitute accordingly for the timestamp and release that you’re working with.

Creating an image file

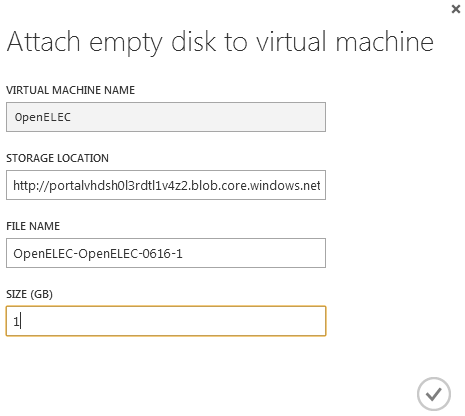

First we need an additional disk to pretend to be the SD card. Hit the attach button in the Azure portal and add a 1GB disk:

The new disk will take a while to provision, and once that’s done a reboot is needed to allow the OS to see it.

sudo reboot now

Wait a minute or two and reconnect via SSH. Then ensure that the newly created disk is clean:

sudo dd if=/dev/zero of=/dev/sdc bs=1M

Next up we need to modify the create_sdcard script. First create a copy of it (we will use this later for automated builds):

cd ~/OpenELEC.tv/releases/ cp OpenELEC-RPi.arm-devel-timestamp-release/create_sdcard .

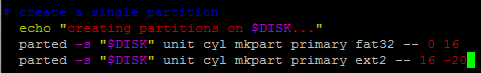

Now we need to edit the script to create partitions that are smaller than the fake SD card:

vi create_sdcard

Now hit /16 -2 to find the right line then hit A to append to that line, add a 0 on the end, hit Esc to exit insert mode then :wq and Enter to write the updated file and quit out of the editor[1].

Next we create the image:

cd OpenELEC-RPi.arm-devel-timestamp-release sudo ../create_sdcard /dev/sdc sudo dd if=/dev/sdc of=../release.img bs=1M count=910

The raw image file is too large to move around, so zip it up and delete the original:

cd .. zip release.img.zip release.img sudo rm release.img

Web serving

To serve up the build releases and images requires a web server. This isn’t part of the standard Ubuntu build on Azure so install it with:

sudo apt-get install apache2

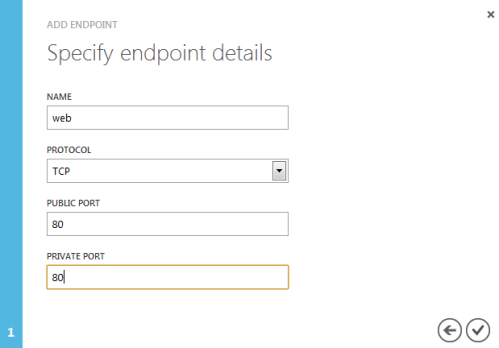

Next it’s necessary to open up the firewall on Azure, which is done via the ENDPOINTS configuration:

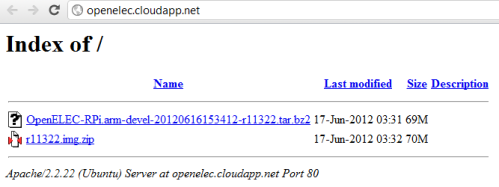

Once that’s done it should be possible to access the web server over the Internet:

With that done, it’s just a matter of removing the default index.html page, and copying over the files to be served:

sudo rm /var/www/index.html sudo cp ~/OpenELEC.tv/target/OpenELEC-RPi.arm-devel-timestamp-release.tar.bz2 /var/www sudo cp ~/OpenELEC.tv/releases/release.img.zip /var/www

The files will now be available over the web:

Automating it all

If you’ve got this far then I hope you’ve had fun. You could push out new releases every few hours by following the same steps, but it’s a bit labour intensive. Much better to create a script to run through the steps for you:

cd ~/OpenELEC.tv vi doit.sh

Hit A and paste in the following script (in PuTTY paste can be done by hitting both mouse buttons; don’t try to select the code below as that will copy over extraneous line numbers – just hover near the top right and a handy copy button will emerge):

#!/bin/bash # Outer loop for build and image while : do # Inner loop for git pull while : do GIT=$(git pull) echo $GIT if [ "$GIT" = 'Already up-to-date.' ] then echo 'Waiting half an hour for another pull at Git' sleep 1800 else echo 'Kicking off the build and post build processes' break fi done # Delete old build rm -rf build.OpenELEC-RPi.arm-devel # Make release PROJECT=RPi ARCH=arm make release # Set env vars for release package name TARBALL=$(ls -t ~/OpenELEC.tv/target | head -1) BUILD=$(echo $TARBALL | sed 's/.tar.bz2//') RELEASE=$(echo $BUILD | sed 's/.*-r/r/') # Copy release build to web server sudo cp ~/OpenELEC.tv/target/$TARBALL /var/www cp ~/OpenELEC.tv/target/$TARBALL /mnt/box/OpenELEC # Unpack release cd ~/OpenELEC.tv/releases tar -xvf ~/OpenELEC.tv/target/$TARBALL # Wipe virtual SD sudo dd if=/dev/zero of=/dev/sdc bs=1M # Move into release working directory cd ~/OpenELEC.tv/releases/$BUILD #Run script to create SD card sudo ../create_sdcard /dev/sdc # Make an image file sudo dd if=/dev/sdc of=../$RELEASE.img bs=1M count=910 # Compress release file zip ../$RELEASE.img.zip ../$RELEASE.img # Remove image file sudo rm ../$RELEASE.img # Copy zipped image to web server sudo cp ../$RELEASE.img.zip /var/www cp ../$RELEASE.img.zip /mnt/box/OpenELEC # Go back to OpenELEC directory cd ~/OpenELEC.tv # Loop back to start of script done

Once that’s done save the file by hitting Esc :wq Enter. Then make the script executable and start it (don’t forget to be running inside of a screen session first so that it doesn’t matter if the SSH session is killed):

chmod +x doit.sh ./doit.sh

OpenELEC will now build each time there’s an update and the release package and image will be automatically server up over the web.

Conclusion

In this two part howto I’ve run through all the steps needed to automatically build OpenELEC for the Raspberry Pi in the cloud:

- Signing up to a cloud service

- Installing dependencies

- Making the build

- Creating images from the build

- Serving images up on the web

- Automating the process

Updates

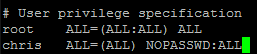

Update 1 (17 Jun 2012) – The script will pause and wait for a password when it bits that need sudo (after the build is done). This can be fixed by setting up sudo to not need a password for your account:

sudo visudo

Add a line ‘username (ALL) NOPASSWD:ALL’ like this:

Then hit Ctrl-X Y Enter to save and exit

I’ve also noticed that I left the lines in that copy the files to a folder on box.net in addition to the web server. This will fail (without causing any issues) unless you have box.net account mounted at /mnt/box and a folder called OpenELEC within it. This howto describes how to mount box.net using WebDAV.

Update 2 (19 Jun 2012) – My Azure account has been disabled, so none of the URLs in this howto will work.

Notes

[1] If editing goes horribly wrong then hit Esc q! Enter and say Y to saving without changes. This will simply quit out of the editor.

Filed under: cloud, howto, Raspberry Pi | 4 Comments

Tags: Apache, Azure, build, cloud, openelec, Raspberry Pi, Raspi, virtual machine, VM, VPS, XBMC

Building OpenELEC in the cloud

When I got my Raspberry Pi pretty much the first thing I did with it was to put on OpenELEC, and excellent shrink wrapped package for XBMC. Initially I started compiling it myself on a local virtual machine (VM), but impatience got the better of me and I downloaded an image provided by somebody else. Later I did some builds for myself, and as others seemed to want up to date build packages and images I moved my build process to a virtual private server (VPS) to save the time taken uploading large files over home broadband. In this howto I’ll run through getting your own server in the cloud, configuring it to build OpenELEC and serving up images.

If you came here just looking for OpenELEC builds/images for the Raspberry Pi then what you’re looking for is here.

Picking a cloud

The VPS that I’m using at the moment comes from BigV. I was lucky enough to get onto their beta programme, which means that I’m not presently worrying about server or bandwidth charges.

The most popular cloud is Amazon’s Elastic Computer Cloud (EC2). I’ve had an AWS account since before they launched EC2, so I’m a long time fan of the platform. This does however mean that I’ve not been able to benefit from the free usage tier for new users. As a consequence I only use EC2 for temporary things as leaving the lights on runs up a bill.

For cheap VPS machines it’s always worth checking out low end box, but for a build box be careful that you have sufficient resources – I’d suggest at least 1GB RAM and 25GB disk.

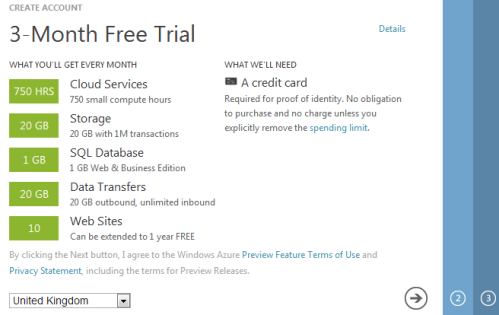

Last week Microsoft announced support for Linux on their Azure cloud, and there’s a 90 day free trial, so for the purpose of this howto I’m going to use that.

Signing up to Azure

First hit the Try it Free button on the free trial page. You’ll need a Microsoft Live account (aka Hotmail account). I’m guessing many people have these already, but if you don’t then you’ll need to sign up[1]. Once logged in there’s a 3 step sign up process:

I chose not to screen shot my credit card details ;-) There’s also no need to give MS your real mobile phone number for the sign up. I used a Google Voice number (see this past post for how to sign up for GV if you’re outside the US).

Once sign up is done it takes a little while for the subscription to be activated, so you’ll probably see something like this:

Once that’s complete it’s time to get started for real.

Creating a virtual machine

I got taken to the ‘new’ Azure portal and had to click through a brief tutorial. Once that was done I was faced with:

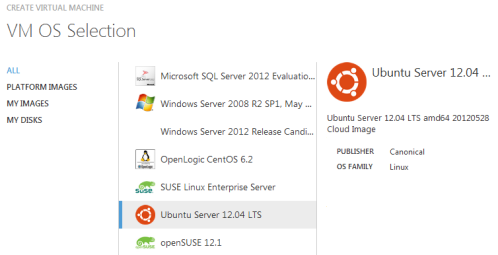

I hit ‘create an item’ then ‘virtual machine’ then ‘from a gallery’ :

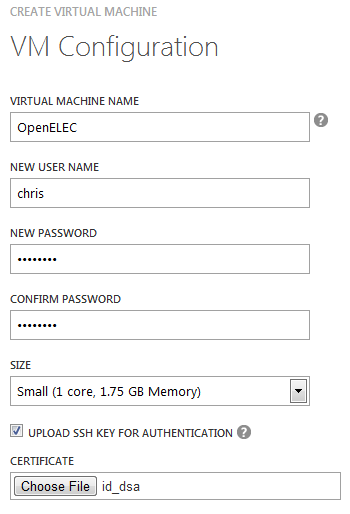

On the next page I filled out the configuration. The SSH piece looks optional, but it’s a good idea to use a key for security, so if you know how to do that then it’s worth using[2]:

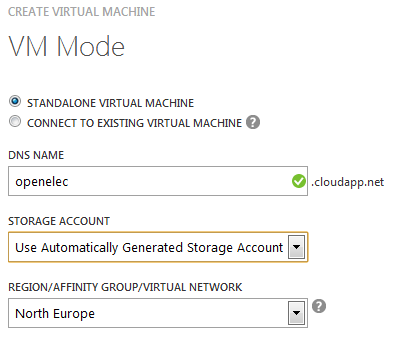

The next page lets you name the machine and choose where it will be hosted. I took the name ‘openelec’, so you’ll have to pick something else – sorry:

I didn’t do anything around availability sets before hitting the tick:

Once all that’s done it will take a little while to provision the machine and start it:

Configuring the VM

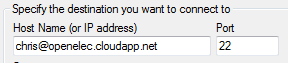

First connect to the VM. I’m using PuTTY:

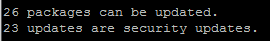

This isn’t a good start:

So run the update tools:

sudo apt-get update sudo apt-get upgrade

Next install the dependencies for building OpenELEC from source:

sudo apt-get install git build-essential gawk texinfo gperf \ cvs xsltproc libncurses5-dev libxml-parser-perl

Compiling for the first time

First pull down the source code from github:

git clone https://github.com/OpenELEC/OpenELEC.tv.git

Then start the build process:

cd OpenELEC.tv screen PROJECT=RPi ARCH=arm make release

The first time around you’ll need to interact with the build process a little to tell it to download additional dependencies. I’ve added in the screen command there so that you can safely cut the SSH connection whilst the build is taking place. If you need to get back to it later then ‘screen -r’ is what’s needed. Screen really is a great tool for anybody using a remote machine, and it’s worth getting to know it in more detail.

That’s it for now

The first compile will take a few hours. In part 2 I’ll cover automating the build process, and setting up a web server to host the release packages and images.

Updates

Update 1 (22 Jun 2012) – My Azure account was disabled after a couple of days, which turns out to be because the trial only bundles 1M I/Os to storage (or 10c worth per month). On that basis it seems that Azure isn’t a suitable cloud for this purpose. It was a fun experiment, but a trial that only works meaningfully for around 7-8 days out of 90 isn’t much use. When I get time I’ll do another guide on using Amazon (or some other IaaS that offers a free trial without silly I/O limits).

Notes

[1] I realize that open source purists are probably recoiling in horror at this stage. Please go back to twiddling with Emacs. I’m an open source pragmatist (and I’d hope that ESR wouldn’t see much harm from closed source here).

[2] I plan to do another howto on using the Raspberry Pi to access a home network where I’ll go into a lot more detail on SSH and keys. Azure seems very fussy about the format of keys, so it’s worth checking out this howto.

Filed under: cloud, howto, Raspberry Pi | 2 Comments

Tags: Azure, build, cloud, openelec, Raspberry Pi, Raspi, virtual machine, VM, VPS, XBMC

Password dump checking

Leaks of (badly secured) password files seem to be big news at the moment. In many cases people set up sites to allow you to see if your password was in the leak – but who knows whether these sites are trustworthy. That’s not a risk I’m happy to take.

Python provides a reasonably simple way to test:

>>> import hashlib

>>> h = hashlib.new(‘sha1’)

>>> h.update(‘password‘)

>>> h.hexdigest()

‘5baa61e4c9b93f3f0682250b6cf8331b7ee68fd8’

Once you have the hash of your password then just search for it in a copy of the leaked dump (normally these spread pretty quickly and can be found easily online).

You can also use this approach to identify passwords that aren’t in such dumps (and thus likely more secure against dictionary attacks where the dictionaries are updated as a result of leaks).

NB I initially tried to use the sha1sum command on Ubuntu to do this, but it wasn’t returning correct hashes (probably due to trailing CRs and/or LFs).

Filed under: howto, security | 2 Comments

Tags: check, checker, leak, password, python, SHA1