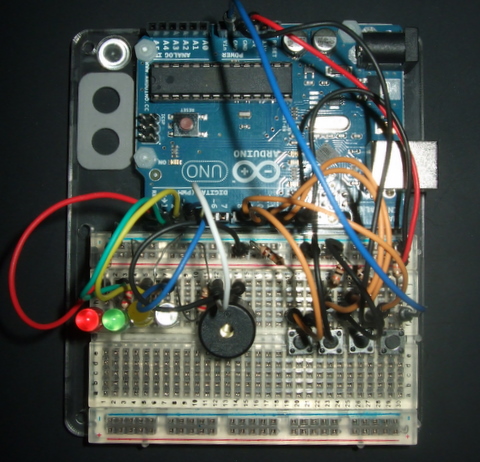

Arduino Simon

I My son got a great Xmas present in the shape of a Starter Kit for Arduino from Oomlout. After doing some of the basic projects I decided we needed something that we could get our teeth into. After a little pondering Simon came out as a worthwhile challenge. Back in the 80s I’d written a version of Simon that was published in Commodore Computing International, so I thought it would be fun to do a hardware version. A bit of poking around the web revealed that this has been done before, but I decided to start from scratch rather than copying the design and code from others (otherwise where’s the fun?).

I expected that this would be a project that might take a few weekends of tinkering, but in the end I had a playable system done in around 90 minutes. Arduino/Processing is a really productive environment, especially if you’re already familiar with electronics prototyping and a bit of C.

The electronics

- Lights – 4 LEDs (Red, Green, Yellow and Blue) between digital output pins and ground with appropriate series resistors.

- Sound – a piezo buzzer between a digital output pin and ground.

- Buttons – 4 – between ground and digital inputs. Right now I have 10k pull up resistors, but they’re probably not necessary. Tip – twist the legs of PCB mount buttons through 90 degrees to stop them pinging out of the breadboard.

The code

I’ll let the code speak for itself, but I’ve put it at the bottom to avoid breaking the flow of things[1]. Update 17 Jan – the original code is below, but revised code is on github.

Todo

- Change the tones so that the match up with the original Simon.

- Check for when a correct sequence of 20 is entered, and do some sort of winning ritual (right now the array will just overflow).

- Resequence the inputs. Blue was on Pin 13, but that was before I discovered that Pin 13 is special.

- Make use of the internal pull up resistors for the buttons (and ditch the 10K ones on the board).

- Progressively speed things up when the sequence gets longer.

- Put the code up on Github.

And then

The kids have really got into playing with this, so I’ve bought some components to transfer things onto a more permanent stripboard based version.

I’m also tempted to see if I can transfer things over to an MSP430 based microcontroller. That would be much cheaper to make a permanent toy out of (especially since TI send out free samples), but it brings with it the extra challenge of having to multiplex inputs and outputs as the MSP430s aren’t graced with the number of pins found on Arduino’s ATMega chip. This would probably involve Charlieplexing the LEDs and coming up with a resistor ladder for input.

Update 22 Jan – I did some follow up posts covering the stripboard build and with some diagrams of the original.

[1] The code:

const int led_red = 1; // Output pins for the LEDs

const int led_green = 2;

const int led_yellow = 3;

const int led_blue = 4;

const int buzzer = 5; // Output pin for the buzzer

const int red_button = 10; // Input pins for the buttons

const int green_button = 11;

const int yellow_button = 12;

const int blue_button = 9; // Pin 13 is special - didn't work as planned

long sequence[20]; // Array to hold sequence

int count = 0; // Sequence counter

long input = 5; // Button indicator

/*

playtone function taken from Oomlout sample

takes a tone variable that is half the period of desired frequency

and a duration in milliseconds

*/

void playtone(int tone, int duration) {

for (long i = 0; i < duration * 1000L; i += tone *2) {

digitalWrite(buzzer, HIGH);

delayMicroseconds(tone);

digitalWrite(buzzer, LOW);

delayMicroseconds(tone);

}

}

/*

functions to flash LEDs and play corresponding tones

very simple - turn LED on, play tone for .5s, turn LED off

*/

void flash_red() {

digitalWrite(led_red, HIGH);

playtone(1915,500);

digitalWrite(led_red, LOW);

}

void flash_green() {

digitalWrite(led_green, HIGH);

playtone(1700,500);

digitalWrite(led_green, LOW);

}

void flash_yellow() {

digitalWrite(led_yellow, HIGH);

playtone(1519,500);

digitalWrite(led_yellow, LOW);

}

void flash_blue() {

digitalWrite(led_blue, HIGH);

playtone(1432,500);

digitalWrite(led_blue, LOW);

}

// a simple test function to flash all of the LEDs in turn

void runtest() {

flash_red();

flash_green();

flash_yellow();

flash_blue();

}

/* a function to flash the LED corresponding to what is held

in the sequence

*/

void squark(long led) {

switch (led) {

case 0:

flash_red();

break;

case 1:

flash_green();

break;

case 2:

flash_yellow();

break;

case 3:

flash_blue();

break;

}

delay(50);

}

// function to build and play the sequence

void playSequence() {

sequence[count] = random(4); // add a new value to sequence

for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) { // loop for sequence length

squark(sequence[i]); // flash/beep

}

count++; // increment sequence length

}

// function to read sequence from player

void readSequence() {

for (int i=1; i < count; i++) { // loop for sequence length

while (input==5){ // wait until button pressed

if (digitalRead(red_button) == LOW) { // Red button

input = 0;

}

if (digitalRead(green_button) == LOW) { // Green button

input = 1;

}

if (digitalRead(yellow_button) == LOW) { // Yellow button

input = 2;

}

if (digitalRead(blue_button) == LOW) { // Blue button

input = 3;

}

}

if (sequence[i-1] == input) { // was it the right button?

squark(input); // flash/buzz

}

else {

playtone(3830,1000); // low tone for fail

squark(sequence[i-1]); // double flash for the right colour

squark(sequence[i-1]);

count = 0; // reset sequence

}

input = 5; // reset input

}

}

// standard sketch setup function

void setup() {

pinMode(led_red, OUTPUT); // configure LEDs and buzzer on outputs

pinMode(led_green, OUTPUT);

pinMode(led_yellow, OUTPUT);

pinMode(led_blue, OUTPUT);

pinMode(buzzer, OUTPUT);

pinMode(red_button, INPUT); // configure buttons on inputs

pinMode(green_button, INPUT);

pinMode(yellow_button, INPUT);

pinMode(blue_button, INPUT);

randomSeed(analogRead(5)); // random seed for sequence generation

//runtest();

}

// standard sketch loop function

void loop() {

playSequence(); // play the sequence

readSequence(); // read the sequence

delay(1000); // wait a sec

}

Filed under: Arduino, howto, making | 4 Comments

Tags: arduino, breadboard, button, buzzer, code, electronics, game, LED, pin 13, Simon

I ordered this card to go in my latest Microserver running the Windows 8 Developer Preview, but before it arrived I found an old NVidia Quadro NVS 285 lying around, which fitted the bill perfectly for doing dual DVI. My next thought was to upgrade the NVidia Geforce 210 in my (now rarely used) workstation. Sadly it doesn’t fit in there, as the heatsink bends around to the other side of the board, which in my workstation means it’s fighting a losing battle against the RAID card below for space. I think it would fit fine into the Microserver, provided that the next door PCIe slot isn’t occupied (or filled with something small).

I could have put it into my ‘sidecar’ Microserver, but that would be a waste since I pretty much never use that machine locally. Thus my daughter’s box became the winner. This had an old X800 in it, which despite being on the recommended hardware list appeared to be insufficient for the task of running Lego Universe.

Installation

The fold over heat sink wasn’t a problem without another board directly below. On booting up the machine (running Windows 7 x64) didn’t pull down a new driver, going for Standard VGA and the low resolutions that entails. I was however able to update the driver via Windows and get back to glorious 1920×1080. This seemed like a better idea than the likely old drivers on the supplied CD or the huge 100MB+ download from ATI (which must have huge amounts of annoying cruft in it).

Performance

The 2D performance took a slight step back in Windows Experience Index (5.8 -> 4.6) but the 3D performance leapt up to 6.1. Oddly this means that the oldest PC still in use in the house now has the highest WEI. Bringing Direct X 10 and 11 to the table surely helps, and the good news is that Lego Universe now starts up perfectly.

Conclusion

Performance wise this is the card I should have bought in favour of the GeForce 210, but I’d have been out of luck fitting it to the intended machine due to the fold over heat sink. If you have sufficient space, and want a low end GPU that can drive a decent size monitor then this card seems to beat the NVidia in almost every measure. It looks like other OEMs like VisionTek make similar cards with different heat sinks, which may in some cases be a better fit. I’m happy that my daughter’s machine can now run stuff that didn’t work before.

Update 1 – 9 Dec 2011 – Toms Hardware has a really good comparison chart showing the relative performance of various families of NVidia, ATI and Intel chipsets.

Filed under: review, technology | Leave a Comment

Tags: 5450, benchmark, DX10, DX11, fit, HD, heatsink, Lego Universe, Microserver, Radeon, Sapphire, WEI

I like to get familiar with new versions of Windows early in the cycle, so it was great to see the Developer Preview being made available ahead of a beta.

First impressions

The new Metro interface hits right between the eyes. I can’t say that I’m a fan yet. It seems well adapted to touch screens, but I’m not comfortable with it on a regular desktop monitor. The worst bit is that it doesn’t take long before needing to scroll over to icons for recently installed apps that sit off screen. A monitor in portrait orientation exacerbates the issue.

Luckily it’s fairly easy to escape back to the familiar desktop, where if regularly used apps are pinned there’s rarely any reason to leave – except the Start button goes right back to Metroland.

The little things

Windows has had accessories for as long as there has been Windows – things like calculator and paint. The executables are still there, but I haven’t yet found the new equivalent of the Accessories folder.

My test hardware

As the HP Cashback deal makes them such a bargain I got myself another one of their wonderful little Microservers. This time it’s one of their new N40L models, which has a slightly faster 1.5GHz Turion processor (versus the older 1.3GHz Athlon) 2GB or RAM as standard [1] (was 1GB) and a lower rated PSU (so hopefully more frugal than ever).

Wireless

The Microserver isn’t somewhere that I can plug it into a wired network, so I got a cheap USB wireless adaptor from eBay. I needed to install drivers to get it going, but the process wasn’t too painful.

Video

The Microserver only has a VGA output, which isn’t a good way to drive the sideways T configured screens on my desk. Luckily I had an old NVidia Quadro NVS 285 card lying around along with a Dual-DVI cable – this is small enough and low power enough to suit the Microserver perfectly [2]. This time around no messing with drivers – on powering up Windows 8 sprang to glorious life across both screens. All I had to do was reorient the left screen for portrait orientation.

If you want to drive a couple of screens from a Microserver, and don’t plan on playing 3D games, then these cards are cheap, readily available and work great.

KVM

So that I can switch between my regular machine and the Microserver I got a USB KVM switch. The V bit is in my case utterly pointless, as I don’t want to switch video, but it seems that switches that just do USB keyboard and mouse aren’t common/affordable [3]. It works pretty well – I just have to double tap Scroll Lock to switch between machines. The only issue is that it insists on having the appropriate VGA cable plugged in – lucky for me the Microserver and my laptop docking station have (now superfluous) VGA outputs.

Overall

If you stay on the desktop, then Windows 8 is very familiar to those who have got used to Windows 7 (or even Vista before). So far everything I’ve installed has run fine – though that’s not too much, as I don’t want to invest time in a build that will time out as the product release cycle grinds forward. This is clearly evolutionary (like 2000 -> XP, or Vista -> Windows 7) rather than revolutionary, but given the issues with previous revolutionary releases that’s probably a good thing.

[1] I got another 2GB in anticipation of running a VM or two in VirtualBox. I should also mention that the preview runs fine in VirtualBox.

[2] Right now this is running without a proper fixing bracket, as the card came with a regular size one rather than low profile, but I’m hopeful that I’ll find a bracket somewhere to fix that up.

[3] As most decent monitors now have multiple digital inputs I don’t quite get why this is a gap in the market. That said those modern monitors don’t make it as easy as it should be to make the switch. On my TV I can go between inputs with just one button. On most of the monitors I use I find myself having to press two or three to achieve the same thing.

Filed under: review, technology | 4 Comments

Tags: desktop, KVM, Metro, Microserver, N40L, USB, wifi, Windows 8, wireless

OpenVPN

For some time I’ve used SSH tunnels as a means to pretend that I’m somewhere else to avoid geography filters, or to otherwise sneak past content filters. This is fine for regular HTTP(S) traffic from a browser, where it is easy to define a proxy server, but doesn’t work so well for other applications – for example the desktop version of TweetDeck seems to completely ignore proxy settings.

I went in search of a network adaptor that would hook up to an SSH tunnel, and what I found was OpenVPN [1]. I set this up on a small cloud server, a process that I can only describe as trivial – the quick start guide is great. This was quite a contrast to my experience of trying to set up L2TP on Ubuntu a few weeks earlier.

By default the OpenVPN daemon listens on port 443, which is the same port that I normally use for SSH tunnels (as most content filters block the regular port 22 for SSH) [2]. The admin interface runs (over HTTPS) on port 943, though I took the precaution of turning off binding to a public IP [3].

Client installation was also straightforward, a simple download and install followed by putting the IP, username and password into the startup dialogue box.

For those that can’t be bothered with running their own cloud server or VPS there’s a service version called Private Tunnel, which charges by bandwidth consumed rather than any other metric like month, machine or whatever. I’ve not used it myself, and the Ts&Cs aren’t as benign as I’d like, but it may well be the easy/cheap option.

My only complaint is that there’s no iOS support, and this isn’t the sort of thing that can be done with an app – it would need to be baked in to a future version of iOS, and sadly I can’t see why Apple would be in any hurry to do that [4].

[1] As the Wikipedia article explains, OpenVPN doesn’t actually use SSH, but it’s certainly close enough, and achieves what I was looking for.

[2] I have once run into trouble with a very clever filter realising that I was using SSH rather than SSL/TLS, though in that particular case it was happy for me to run SSH over port 22, so no harm done.

[3] If I want to do any admin then it’s straightforward enough to SSH into the box and then run a web connection through a tunnel to the localhost loopback.

[4] There does appear to be some support for jailbroken iOS devices, but that isn’t an option for me if I want my Good for Enterprise client to keep passing its compliance checks. It looks like for the time being I’ll have to stick with using iSSH for an SSH tunnel to one of my VPSs running Squid.

Filed under: howto, review, technology | Leave a Comment

Tags: cloud, filter, iOS, iSSH, Linux, OpenVPN, PrivateTunnel, SSH, SSL, tunnel, Ubuntu, vpn, VPS, Windows

If you don’t already know what Raspberry Pi is then take a look at the Wikipedia entry and their web site.

Their mission to recreate the experiences of 8 bit computing that shaped the lives and careers of my generation is laudable, and I’m sure they will achieve great success.

That’s just the start though. Raspberry Pi based boards are going to be everywhere, and that’s going to change the world as we know it.

One of my favourite SF books of all time is Vernor Vinge’s ‘A Deepness in the Sky‘ – whenever I see snow now there’s a little bit of me thinking ‘the sun went out, and the atmosphere has frozen’. The protagonist of the story, Pham Nuwen, makes use of ‘localisers’ – a sort of smart dust to get up to various sorts of hackery that lets him win the day. The Raspberry Pi may be credit card sized rather than dust sized, but it takes us a step closer to that science fiction becoming a reality.

Prediction 1 – one of the first things to be disrupted will be the hardware thin client business. I expect that within a day of release (maybe even before mainstream release) somebody will put together a package that turns a Raspberry Pi into a client for screen remoting protocols like RDP, ICA, VNC etc. For way too long the hardware thin clients have been too big and too near to the cost of a real PC. $25 and the size of a credit card changes that game. It will then be a matter of months before some enterprising monitor maker decides to build Raspberry Pi into the box – the ecosystem will be irresistible to them.

Prediction 2 – lots of things that have dedicated microcontrollers in them now will start to have a Raspberry Pi instead. I liked the idea of ‘Arduino inside’ that I read about in this story of a guy who hacked his dishwasher. The microcontroller on the Arduino is pretty ancient though. Yes, there are plenty of cheap dedicated microcontrollers out there that are more powerful (I’ve done some tinkering myself with the TI MSP-430), but in the end the flexibility of software normally trumps an efficiency of hardware. At first it will be the hackers and makers putting their Raspberry Pis into ordinary kit, but then manufacturers will catch on that the community will be able to add value to products after they’re launched – making them more desirable.

Of course the original aim of Raspberry Pi – getting kids interested in computers again – will spur many other waves of creation and innovation. I can’t wait to see what happens.

Filed under: Raspberry Pi, technology | 8 Comments

Tags: arduino, hack, hacking, ICA, makers, microcontroller, PCoIP, Raspberry Pi, RDP, thin client, VDI, VNC

Race Against The Machine

I’ve been an avid follow of Andrew McAfee’s Blog ever since JP first pointed me in that direction. He’s clearly a man that understands how technology is reshaping how we do business. Whilst I was on holiday a few weeks ago I noticed that he’d published a book along with Erik Brynjolsson – Race Against The Machine. The subtitle does a great job:

How the Digital Revolution is Accelerating Innovation, Driving Productivity, and Irreversibly Transforming Employment and the Economy

The first thing worth noting is that this book has been published only on Kindle, which means it’s bang up to date. I recall seeing data in there from Aug 2011 – only a couple of months old at the time of reading.

The second important point is that it’s short. I got through it in a couple of hours, and I’m not one of those speed readers who can consume an entire novel in the course of a plane ride.

I don’t intend to pick the book apart here, overall I think it’s a great piece of work – perhaps the first thing I’ve come across that does a good job of explaining why the world, its people and our economies are where they are, and how we might use technology to get us somewhere better. What I do want to do is spend some time picking at the recommendations, as I feel this was the weakest area, and that in pursuit of brevity the authors had failed to securely attach many of their recommendations to their main argument. They have 19 specific steps, which I’ll try to tackle in turn:

- Invest in education, starting with paying teachers more. I find this hard to disagree with initially. As I grew up teaching was an admirable profession, and my teachers seemed to be well enough off. Something changed along the way – the only guy that wanted to go into teaching on my degree course got the worst grade on the entire course (though he did graduate, which was better than a third of the original intake). We do seem to have ended up in a vicious circle of teaching being undervalued by society leading to lowering opinion of the career… I feel the remedy is likely to be more transformational than throwing money at the problem. We still predominantly use 19th century teaching methods, as brilliantly illustrated in this video of Sir Ken Robinson speaking at the RSA, and that’s what really needs to change.

- Hold teachers accountable for performance (by eliminating tenure). Since reading the book I finally got around to watching Waiting for “Superman”, and it seems like tenure (and the Unions that keep it in place) really is a huge problem for the US education system. Of course we don’t have tenure in the UK, and it still feels like education is going down the toilet. Attempts by succesive education secretaries to make teachers more accountable seem to have done nothing more than introduce beureacracy, so this topic needs to be approached with care.

- Separate student instruction from testing and certification. I think this one is aimed at the disastrous no child left behind act and the pernicious unintended consequences it’s had on education in the US by stripping teachers of discretion and putting in place a system that’s there to be gamed.

- Keep K-12 students in classrooms longer. Again a very US centric prescription. Unless the race against (or with) the machine is a zero sum game for the planet then I’d have liked to see global recommendations. What’s the right number of hours for kids to spend in classrooms, and where’s the source data for such a recommendation?

- Skilled immigrant visas. Immigration law is a mess just about everywhere, and usually a political/media hot potato. The public debate is all about keeping the wrong people out rather than allowing the right people in – that’s what needs to change first. The EU experiment shows that a (somewhat) borderless labour market works at an individual and state economic level, but the whole situation is bereft with envy and xenophobia.

- Teach entrepreneurship throughout higher education. Who and how? Teachers aren’t entrepreneurs. In most cases even business school teachers aren’t entrepreneurs. Getting this right means schools engaging in a new way with (local) businesses. I was fortunate enough to take part in such a program whilst at 6th form college (=12th grade) but it ran in the margins rather than the mainstream (during a holiday if I recall). I’d go so far as to say that entrepreneurship might be the wrong target here – how about some of the basic skills needed to run a business – book keeping, marketing, CRM etc.?

- Founders visas. I don’t see the difference between a founder and a skilled immigrant. So why repeat the point? My friend Kirk has also gone to some efforts to point out the flaws in any plan aimed at startups.

- Templates for new businesses. Is starting a business a knowledge management problem that can be resolved by codification of implicit to explicit, and greater uniformity? It’s probably worth looking at the agencies involved and the incentive structure around their activities – essentially who amongst the lawyers, bank managers, accountants etc. has their snout in the trough as part of making this difficult right now?

- Lower government barriers to business creation. Another snout in the trough problem, only this time it’s public and elected officials. The issue doesn’t stop at business creation either – in many cases established firms use legislation to create barriers to entry to deal with the problem of disruption from below. The authors recognise the political and economic complexities, but offer no explanation of how to deal with them. To resolve this one we need to recognise that it’s not just the 3rd world that’s riddled with corruption – it’s endemic – just dressed up more nicely as ‘lobbying’ and ‘political donations’. The founding fathers in the US recognised the need to separate church and state; we must now do something to separate state (or at least the political structure of state) and money. Politics should be a calling not a career.

- Investment in infrastructure. It does appal me whenever I visit the US how shoddy the basic infrastructure looks and feels, but things seem to work despite that. Also roads and railroads are the infrastructure of the industrial age rather than the information age. Would a comparatively smaller investment in say fibre to the doorstep be more useful than bigger roads with fewer pot holes? I’d suggest a look at data from S Korea might provide some illumination here.

- Increase funding for basic research. Another one where I’d like to see some evidence. Is China pulling ahead because their government does more of this? Has the level of basic research worldwide been able to find a different level because of the open and collaborative nature of the Internet? How do we know that present levels of investment are wrong?

- Keep hiring and firing as easy as possible. Why are the authors even talking about a system grounded in redundant concepts like a job for life? This one gets answered at 14.

- Make it more attractive to hire people than buy technology. This feels like a pure Luddite argument. The race against the machine will not be won by making the machine pay higher taxes.

- Decouple benefits from jobs. Again, evidence from countries that run different systems could be used to construct an argument for optimisation. Denmark and the Netherlands are referenced here, but what are they doing, and what has it accomplished? If the US sticks with its approach to health insurance then why should big firms be able to negotiate a better deal than individuals? Isn’t it dumb of insurers to allow employees of big firms to be lumped together rather than considering the risks of an individual? Or is their some dumb concept of fairness at work here where the deck is allowed to be stacked one way but not another?

- Don’t rush to regulate new network businesses. It would be interesting here to have comparison of how different countries regulated the Internet as it emerged, and the effect that this had on associated economic activity (both pure play net businesses and other businesses supported by the Internet).

- Eliminate home mortgage subsidy. The tip of the iceberg of a bigger problem where cheap and easy debt collided with limited capital. The trick is perhaps to find an investment vehicle that can be indexed against real estate markets for those who want to have their cake (accumulation of capital in property) and eat it (rent wherever they wish to go). There is probably a point to be made here on sales tax for property transactions also.

- Reduce subsidies to financial services. The sector was attracting too many of the brightest and best long before the realities of too big to fail were demonstrated or understood. The issue we face at the moment is that the smart people within financial services are doing a better job of gaming the system than those outside.

- Reform the patent system. I couldn’t agree more with this one. Software patents are a disaster, and we seem to have a fundamental mismatch between the duration of patents (to suit the pharma industry) and the lifetime of technology in other sectors. The only winners seem to be lawyers, but then the US is run by a lawyer elite.

- Shorten copyright and increase flexibility of fair use. This is particularly true for software – why should stuff that’s obsolete (e.g. Windows XP) be protected decades past the end of its useful life, and who are the rent seekers that think this is a good idea. Almost nothing being created today that isn’t explicitly put into the public domain or creative commons will fall into the public domain within our lifetimes.

Filed under: review, technology | Leave a Comment

Tags: #racemachine, copyright, economics, education, employment, entrepreneur, founders visa, immigration, Internet, patents, politics, race against the machine, regulation, review, SMEs, startups, technology

A few weeks ago I attended a summit on advanced persistent threats (APTs)[1] run by on of the major security vendors. So that people could speak freely there it used Chatham House Rules, so sadly I can’t attribute the piece of insight that I’m going to share here.

About five or six years ago I wrote a security monitoring baseline, in which I started out with a statement along the lines of:

All security controls should be monitored, and such monitoring should be aggregated and analysed so that appropriate action can be taken.

The lead point here is that if you have a security control that isn’t properly monitored then at best it will give you a forensic record to be analysed after something so bad has happened that it’s obvious. Most likely that control is useless. If the control got put there to satisfy an auditor then a) they’re too easily satisfied and b) they’ll be back later when they realise the rror of their ways, sooner if something bad happens.

Since then it feels like the practice of security monitoring has matured. Most sufficiently large organisations now have security operations centres (SOCs) that employ some sort of security information/event management tool(s). In many cases organisations have discovered that running a SOC on their own isn’t a good use of highly specialised resource, and have engaged some sort of managed security service provider (MSSP) to do the heavy lifting for them.

Getting back to APTs – the whole point is that they’re different. This type of attacker isn’t generically after anything of value – they want something specific, and they want to take it from you. A different discipline is needed to identify and deal with such attackers, and this is where the eyeball analogy comes in – for the eyeballs on security monitoring we need both rods and cones:

- Rods – this is the picture you get from a traditional SOC. Monochrome, but works in low light. You can probably outsource much of this to an MSSP. Whoever does this will be reacting to a near real time environment.

- Cones – these add the colour. You may need to shine a light into the nether regions of your network to discern what’s going on. You need people that understand the business context of what an attacker is going after – the self awareness of knowing where the crown jewels are secured. Those people will have to actively search for the low and slow threats – matching the patience and technical subtlety of the attacker

[1] I actually prefer Josh Corman’s label of Adaptive Persistent Adversaries, but Schneier is right that we need a label to rally around, and APT seems to be the one that’s stuck.

Filed under: security | 1 Comment

Tags: APT, cones, eye, eyeball, monitoring, MSSP, rods, security, SEM, SIEM, sim, SOC

If I’d had a dummy in my mouth then I’d have definitely spat it when I read this:

The article makes out the NYSE is pitching OpenMAMA directly against AMQP. Luckily it’s sensationalist twaddle, and the author obviously doesn’t appreciate the difference between an API, which is what OpenMAMA is, and a wire protocol, which is what AMQP is.

The article makes out the NYSE is pitching OpenMAMA directly against AMQP. Luckily it’s sensationalist twaddle, and the author obviously doesn’t appreciate the difference between an API, which is what OpenMAMA is, and a wire protocol, which is what AMQP is.

Whilst the tech press might like to stir up a fight, I personally look forward to seeing OpenMAMA and AMQP working together (just as JMS and AMQP do). Yes, I’m sure that NYSE will continue to push their proprietary messaging wire protocol – the one that they got when they bought Wombat; but that’s all part of the technology industry’s rich tapestry.

I’d also note that MAMA isn’t new, it seems that it was first released around six years ago. Props to NYSE for opening it up though, I’m really liking how the Open-* world is well, opening more every day.

Filed under: technology | 1 Comment

Tags: AMQP, API, MAMA, NYSE, open, OpenMAMA, press, wire protocol

One weekend, four upgrades

I found myself upgrading a bunch of stuff over the last weekend, which gave me cause to reflect on what was good, and what was not so good.

Android

First up was my ZTE Blade, which I’ve had running Cyanogen Mod. I wasn’t super impressed with version 7.0. There were few things that it did better than the modified Froyo build I’d previously had, and a few things didn’t work – like the FM Radio. Version 7.1 promised to fix that. The FAQ told me to use ROM Manager to do the upgrade, so I did. The whole process took place over the air, and after waiting for everything to download and install my phone was just better – all my apps and data were still there.

Ubuntu

Next was Ubuntu. I downloaded the server build of 11.10 (using BitTorrent as usual), but I already had a VM that I’d built with Alpha 3. A simple ‘apt-get dist-upgrade’ was all that was needed.

iOS5

This is where it got messy. I’d waited a few days until the load came off Apple’s infrastructure, having read the tweets about all the issues folk were having. It seemed like the main problem was simply getting the upgrade – how wrong I was about that.

First there was the obligatory iTunes update before I could get started, and the OS restart that went along with that – inconvenient, but not the end of the world.

I depend on my iPhone more than my iPad, so the iPad went first. Things did not go well. The upgrade process hung and/or failed in inexplicable ways at a number of stages. In the end I lost all of my videos (in the AVPlayer HD app) and all of my music (settings just seemed to disappear from iTunes), a bunch of extraneous apps from my iPhone also got installed. Luckily the rest of my data/settings seemed to survive, but it was a messy experience. I chose not to use iCloud.

The subsequent iPhone upgrade went a little better, but was also turbulent experience. Why is it that Apple needs to effectively backup and restore all my apps and data, and wipe the machine in between, rather than just patch up the OS in place? Clearly lots of lessons to be learned here from the OSS community.

Kindle

I upgraded my Kindle (from 3.1 to 3.3) whilst sorting out the iOS mess. It was a rawer experience than the Android or Linux updates, but very simple – download the new firmware, copy it over, invoke the update.

Conclusion

The Android upgrade experience was super impressive – everything that’s been promised with iCloud (but that we will wait for the next iOS update for to see if it’s for real). The Cyanogen Mod guys are really showing the world how it should be done – Google (and the handset makers) should have baked this in from the start, but it’s good to see a project bridging the gap. I was also impressed by Ubuntu – as I’ve become too accustomed to having to start afresh whenever I’ve used an alpha or beta version. Upgrading the Kindle was painless, but I’ve not really noticed anything new or improved. My iPhone doesn’t seem any better either, but it was a fight getting it there. Thankfully I do notice the better Safari on the iOS5 iPad, but it’s hard to say that it was worth the grief.

Filed under: could_do_better, did_do_better, grumble, technology | 1 Comment

Tags: 11.10, android, cyanogen, Cyanogen Mod, distribution, iOS, iOS5, iPad, iphone, kindle, Linux, upgrade, ZTE Blade

I run a bunch of Linux (mostly Ubuntu) VMs on my main machine at home, which happens to be a laptop. I use VirtualBox, but what I have to say here is probably applicable to most host based virtualisation environments.

My requirements are pretty simple:

- The VMs need to be able to access the Internet via whatever connection the laptop has.

- Internet access should continue to work if I switch between wired and wireless connections (e.g. if I undock the laptop and take it into the lounge).

- I need to be able to access the VMs over SSH using PuTTY.

- Not attached – obviously

- NAT – provides Internet access, but doesn’t give an IP that I can SSH to

- Bridged – makes me choose between wired or wireless

- Internal network – doesn’t do any of the things I want (at least not without much extra work/plumbing)

- Host only – doesn’t give me Internet access

- Generic driver – don’t even go there

- NAT – appears as eth0 – provides Internet access whether I’m using wired or wireless

- Host only – appears as eth1 – provides an IP that I can connect to using PuTTY

# Host only interface auto eth1 iface eth1 inet dhcp

Filed under: howto, technology | 2 Comments

Tags: bridged, eth0, eth1, host only, howto, internal, Linux, NAT, network, networking, Putty, SSH, Ubuntu, VirtualBox, virtualisation, virtualization