Turning a Twitter thread into a post.

I wrote about the performance of AWS’s Graviton2 Arm based systems on InfoQ

The last 40 years have been a Red Queen race against Moore’s law, and Intel wasn’t a passenger, they were making it happen. I used to like Pat Gelsinger’s standard reply to ‘when will VMware run on ARM?’

It boiled down to ‘we’re sticking with x86, not just because I used to design that stuff at Intel, but because even if there was a zero watt ARM CPU it wouldn’t sufficiently move the needle on overall system performance/watt’. And then VMware started doing ARM in 2018 ;)

Graviton 2 seems to be the breakthrough system, and it didn’t happen overnight – they’ve been working on it since (before?) the Annapurna acquisition. AWS have also been very brisk in bringing the latest ARM design to market (10 months from IP availability to early release).

Even then, I’m not sure that ARM is winning so much as x86 is losing (on ability to keep throwing $ at Moore’s law’s evil twin, which is that foundry costs rise exponentially). ARM (and RISC-V) have the advantage of carrying less legacy baggage with them in the core design.

I know we’ve heard this song before for things like HP’s Moonshot, but the difference this time seems to be core for core the performance (not just performance/watt) is better. So people aren’t being asked to smear their workload across lots of tiny low powered cores.

So now it’s just recompile (if necessary) and go…

Update 20 Mar 2020

Honeycomb have written about their experiences testing Graviton instances.

Filed under: cloud | Leave a Comment

Tags: ARM, aws, Graviton2, x86

AnandTech has published Amazon’s Arm-based Graviton2 against AMD and Intel: Comparing Cloud Compute which includes comprehensive benchmarks across Amazon’s general purpose instance types. The cost analysis section describes ‘An x86 Massacre’, as while the pure performance of the Arm chip is generally in the same region as the x86 competitors, its lower price means the price/performance is substantially better.

Filed under: cloud, InfoQ news | Leave a Comment

Tags: ARM, aws, benchmark, Graviton2, performance, x86

Further thoughts on TornadoVM

TornadoVM was definitely the coolest thing I learned about at QCon London last week, which is why I wrote up the presentation on InfoQ.

It seems that people on the Orange web site are also interested in the intersection of Java, GPUs and FPGA, as the piece was #1 there last night as I went to bed, and as I write this there are 60 comments in the thread.

I’ve been interested in this stuff for a very long time

and wrote about FPGA almost 6 years ago, so no need to go over the same old ground here.

What I didn’t mention then was that FPGA was the end of a whole spectrum of solutions I’d looked at during my banking days as ways to build smaller grids (or even not build grids at all and solve problems on a single box). If we take multi core CPUs as the starting point, the spectrum included GPUs, the Cell Processor, QuickSilver and ultimately FPGAs; and notionally there was a trade off between developer complexity and pure performance potential at each step along that spectrum.

Just In Time (JIT) Compilers are perfectly positioned to reason about performance

Which means that virtual machine (VM) based languages like Java (and Go[1]) might be best positioned to exploit the acceleration on offer.

After all the whole point of JIT is to optimise the trade-off between language interpretation and compilation, so why not add extra dimensionality to that and optimise the trade-off between different hardware targets.

TornadoVM can speculatively execute code on different accelerators to see which might offer the best speedup. Of course that sort of testing and profiling is only useful in a dev environment, once the right accelerator is found for a given workload it can be locked into place for production.

It’s just OpenCL under the hood

Yep. But the whole point is that developers don’t have to learn OpenCL and associated tool chains. That work has been done for them.

Again, this is powerful in addressing trade-offs, this time between developer productivity and system cost (ultimately energy). My FPGA experiment at the bank crashed on the rocks of it would have cost $1.5m in quants to save $1m in data centre costs, and nobody invests in negative payouts. If the quants could have kept on going with C++ (or Haskell or anything else they liked) rather than needing to learn VHDL or Verilog then it becomes a very different picture.

Which means it’s not real Java

So what, arithmetic doesn’t need fancy objects.

There’s some residual cognitive load here for developers. They firstly need to reason about suitable code blocks, and apply annotations, and then they must ensure that those code blocks are simple enough to work on the accelerator.

If I had greater faith in compilers I’d maybe suggest that they could figure this stuff out for themselves, and save developers from that effort; but I don’t the compiler will not save you.

Conclusion

My FPGA experiment some 15 years ago taught me a hard lesson about system boundaries when thinking about performance, and the trade-off between developer productivity and system productivity turns out to matter a lot. TornadoVM looks to me like something that’s addressing that trade-off, which is why I look forward to watching how it develops and what it might get used for.

Updates

10 Mar 2020 I’d originally written ‘TornadoVM doesn’t (yet) speculatively execute code on different accelerators to see which might offer the best speedup, but that’s the sort of thing that could come along down the line‘, but Dr Juan Fumero corrected me on Twitter and pointed to a pre-print of the paper explaining how it works.

Note

[1] Rob Taylor at Reconfigure.io worked on running Golang on FPGA

Filed under: software | Leave a Comment

Tags: compiler, FPGA, Go, golang, GPU, java, JIT, TornadoVM, VM

Working From Home

TL;DR

I prefer working from home over the grind of a daily commute. After many years of doing it I’ve been able to refine my working environment to make it comfortable and productive.

Background

As the COVID-19 pandemic bites a bunch of people are working from home who might not be so used to it. Guides like this one from Justin Garrison are showing up, so I thought I’d take a pass at my own.

I’ve more or less worked from home for the past 7 years, which covers my time at Cohesive Networks then DXC. Before that I generally had a work from home day (or two) in a typical week. Now there’s no such thing as a typical week; I work from home whenever I don’t need to be somewhere else – whether that’s the London office, or the Bangalore office (which is where I was supposed to be today).

A (semi) dedicated room

I’ve used 4 different rooms over the years, and in each case it’s been my ‘office’.

- Bedroom 2 had plenty of room for my desk and a guest bed, but that was when $son0 was still a toddler, and when he grew up he needed the space.

- Tiny front room had just enough space, but was an acoustic disaster when the family were home. I was kind of glad when it became our utility room and I was kicked out in favour of the washing machine and tumble dryer (and dog).

- Bedroom 3 was good enough, but didn’t still serve as a family or guest bedroom, which was kind of a waste.

- The loft conversion is perfect – dedicated space at the top of the house away from family noise and other distractions. There’s a futon in there that can be pressed into service for guests.

Desk

Prior to the loft conversion I used a computer unit from Ikea, which was entirely satisfactory in terms of layout and storage. The loft conversion provided an opportunity to get a custom desk made (from kitchen worktop).

Chair

If you’re spending 45 hours a week in a chair then it needs to be a good one that’s not going to cause back trouble. My tool of choice is a Herman Miller Aeron (used from eBay).

Light

The loft conversion has large Velux windows front and back, which provide plenty of natural light during the day (and in the summer I’m glad for the awnings that keep down the heat and glare). During the winter months the ceiling mounted LED down lights see service at the beginning and end of days.

Quiet please

My silent PC means I’m not dealing with fans whirring all day, which really helps with concentration. There’s a bit of background coil whine from power supplies; but then there’s also wind, and rain, and traffic going by.

Big screen(s)

I run a Dell U2715H 27″ 2560×1440 as my main display, which gives me space for two browser sessions docked to each side of the screen (and most of my stuff is done in a browser).

A Samsung 24″ 1920×1080 screen provides extra real estate for full screen apps, including presenting on web conferences etc.

Webcam

I have a Logitech device that dates back to the dark ages before laptops had their own webcams built in, but it’s still perfectly functional. It attaches to mounting points made from Lego and held down with Sugru.

Headset

I can use the webcam mic and monitor speakers for a speakerphone type experience, and that’s great if I’m expecting to be mostly on mute, but can cause echo issues.

When I’m presenting or expecting to talk a lot I have a Jabra 930 that I covered in my previous Headsets (mini review).

Staying healthy in body

I try to stand every hour to keep streaks going on my Apple Watch (and it will sometimes remind me if I’m remiss on that).

The futon provides a useful anchor for sit-ups to keep core strength.

The loft conversion means plenty of flights of stairs to run up and down for glasses of water, cups of tea, and answering the door to the postman and delivery drivers.

My lunchtime routine is to walk the dog to the local shop, whilst listening to a podcast, so that’s exercise, learning and food all taken care of.

Staying healthy in mind

I don’t miss the ‘water cooler’. It’s nice to bump into colleagues when I’m in the office, but I don’t feel bereft of human contact whilst at home. That might be different if I spent less of my days talking to colleagues on various calls.

Time management

Not commuting means not wasting 3hrs each day on train rides and getting to and from stations, but it’s easy for that time to get soaked up by work stuff. I try to force a stop when the family gets home from their days. It’s good to be flexible at times though, and taking a late call from home is a lot less bother than staying late at the office.

Colleagues

Most of the people I work with at DXC also work from home with occasional trips elsewhere to be in the office, visit customers and partners, and attend events; so the company has a decent amount of remote working baked into the culture. That includes time zone sensitivity and management that don’t expect people to be in a particular place.

Conclusion

I’d hate to go back to the daily grind of a commuting job. I think it would make me less productive, and also a lot less happy. Working from home is definitely something I see as a positive, but to make the best of it takes a little work to get the right environment.

Update 18 Mar 2020 – Power and UPS

This post I just saw from Gautam Jayaraman on LinkedIn reminded me of something I’d left out – making sure the lights stay on, or in the case of home working your PC, monitor, router and anything vital connecting them together. I’ve ended up with 4 UPSs dotted around the house, which are vital given the poor quality of my utility electricity supply.

Filed under: culture | 1 Comment

Tags: design, ergonomics, home, office, WFH

Dr Juan Fumero presented at QCon London on TornadoVM, a plug-in to OpenJDK and GraalVM that runs Java on heterogeneous hardware including Graphical Processing Units (GPUs) and Field Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs). Demos during the presentation showed code being speeded up by hundreds of times when running on a GPU vs a CPU.

Filed under: InfoQ news | Leave a Comment

Tags: FPGA, GPU, java

Performance and Determinism

Background

A friend sent me a link to an ‘AI Ops’ company over the weekend asking me if I’d come across them. The product claims to do ‘continuous optimisation’, and it got me wondering why somebody would want such a thing?

Let’s explore the Rumsfeld Matrix

Known knowns

This is where we should be with monitoring. We know how the system is meant to perform, and we have monitors set up to alert us when performance strays outside of those expected parameters (at that point giving us a known unknown – we know that something is wrong, but the cause is yet to be determined).

Such known knowns are predicated on the notion that the performance of our system is deterministic. Expected things happen at the inputs, leading to expected things happening at the outputs, with a bunch of expected transformations happening in the middle.

Computers are superficially very amenable to determinism – that’s why they call it computer science. Modern systems might encompass vast complexity, but we can notionally reason about state at pretty much every layer of abstraction from the transistors all the way up to applications written in high level languages. We have at least the illusion of determinism.

Unknown unknowns

In ‘why do we need observability‘:

When environments are as complex as they are today, simply monitoring for known problems doesn’t address the growing number of new issues that arise. These new issues are “unknown unknowns,” meaning that without an observable system, you don’t know what is causing the problem and you don’t have a standard starting point/graph to find out.

This implies that we have determinism within a bounded context – that which we do understand; but that complexity keeps pushing us outside of those bounds. Our grip on determinism is slippery, and there will be times when we need some help to regain our grasp.

Unknown known

This is the intentional ignorance quadrant, and I think the target for the ‘AI Ops’ tool.

Yes, the dev team could spend a bunch of time figuring out how their app actually works. But that seems like a lot of hard work. And there’s a backlog of features to write. Much easier to buy a box of magic beans neural network to figure out where the constraints lie and come up with fixes.

This confronts the very real issue that getting a deterministic view of performance is hard, so of course people will be tempted to not bother or take shortcuts.

It’s easy to see why this is the case – I’ll provide a couple of examples:

Compilers work in mysterious ways

And so do modern CPUs.

In ‘The compiler will not save you‘ I’ve previously written about how a few different expressions of a completely trivial program that flashes Morse code on an LED result in entirely different object code. If our understanding of the compiler isn’t deterministic for a few dozen lines of C then we’re likely way out of luck (and our depth) with million line code bases.

Also for an embedded system like MSP430 (with its roots in TMS9900) we can reason about how op codes will flip bits in memory. But with modern architectures with their speculative execution and layered caches it gets much harder to know how long an instruction will take (and that’s the thing that lies at the heart of understanding performance).

Alex Blewitt’s QCon presentation Understanding CPU Microarchitecture for Performance[1] lays out some of the challenges to getting data in and out of a CPU for processing, and how things like cache misses (and cache line alignment) can impact performance.

Little changes can make big differences

Back when I ran the application server engineering team at a bank I was constantly being asked to ‘tune’ apps. Ultimately we set up a sub-team that did pretty much nothing but performance optimisation.

Most memorable to me was a customer facing reporting application that was sped up by 10,000x in the space of a few hours. I used Borland’s ServerTrace tool to profile the app, which quickly showed that a lot of time was spent connecting to the backend database. The developers had written their own connection pool class rather than using the connection pools built into the app server. Only that class didn’t actually pool connections. Amateurs 0, App Server Engineers 1. A single line of code changed, one additional config parameter to set up the connection pool, and the app was 30x faster, but it was still horribly slow – no wonder customers were complaining.

With the connection pooling resolved the next issue to become obvious was that the app was making a database call for every row of the report, with a typical report being hundreds to thousands of rows. This of course is what recordsets are for, and another trivial code change meant one database query per report, rather than one for every line of the report, which is MUCH faster.

The journey to understanding starts with the first step

If developers don’t look at the performance of their app(s) then they’re not going to be able to run small experiments to improve them. We have tools like profilers and tracers, we have practices like A/B testing, canary deployments and chaos engineering. But the existence of those tools and practices doesn’t fix anything, they have to be put to work.

Conclusion

Software is hard. Hardware is hard too. Understanding how a given piece of software works on a particular configuration of hardware is really hard. We can use tools to aid that understanding, but only if we care enough to pick them up and start trying. The market is now offering us a fresh batch of ‘AI’ tools that offer the promise of solving performance problems without the hard work of understanding, because the AI does the understanding for us. It might even work. It might just be a better use of our valuable time. But it’s unlikely to lead to an optimal outcome; and it seems in general that developer ignorance is the largest performance issue – so using tools as a crutch to not learning might be bad in the longer term.

Note

[1] The video of his talk to complement the slides is already available to QCon attendees, and will subsequently be opened to public viewing.

Filed under: operations | 1 Comment

Tags: determinism, monitoring, observability, performance, profiling, tuning

TL;DR

Amazon Web Services Certified Solution Architect Professional (AWS CSA Pro) took me a lot more time to study for than Google Cloud Platform Professional Cloud Architect (GCP PCA). They fundamentally test the same skills in terms of matching appropriate services to customer needs, but there’s just more of AWS, and greater fractal detail (that’s often changed over time).

Background

In my previous post on certification I mentioned that DXC’s CTO Dan Hushon asked all his CTOs to get a cloud or DevOps certification prior to the company launch in April 2017. I went for AWS CSA Associate, and after 3 years it was about to expire. So with a half price exam voucher at my disposal I decided to try levelling up to CSA Pro.

I knew it wouldn’t be easy. CSA Pro has a formidable reputation. But I’d already done the Google equivalent with PCA, and by some accounts that was supposed to be harder.

Study time

It took me something like 12 hours to get from Google Associate Cloud Engineer to Professional Cloud Architect using a combination of Coursera, Qwiklabs and Udemy practice tests.

The journey from associate to pro with Amazon was somewhat longer – I’d estimate that I spent something like 42 hours running through Scott Pletcher’s excellent A Cloud Guru course[1], White Papers and Udemy practice tests. Part of that is there are just more services in AWS, and part of that is the practice questions (and answers) just have more detail. The whole thing was more of a grind.

The foreign language comparison

At the end of my 3rd year at high school we’d completed the French curriculum with two weeks left to spare, so our teacher spent those two weeks teaching us Spanish. I learned as much Spanish in two weeks as I’d learned French in three years[2]. Spanish was just easier to get to grips with due to fewer irregularities.

In this case GCP is like Spanish – mostly pretty regular with a small number of exceptions that can easily be picked up, and AWS is like French – lots of irregularity all over the place, which just needs to be learned[3].

And the ground keeps moving under our feet

All the clouds keep growing and changing (which is why they demand re-certification every 2-3 years). But it seems that AWS is perhaps more problematic in terms of things that were true (usually limitations) being invalidated by the constant march forward. In this respect GCP’s progress seems more orderly (and perhaps better thought through), and hence less disruptive to the understanding of practitioners; but maybe that comes at a cost of feature velocity. Cloud services are after all a confusopoly rather than a commodity, and certifications are ultimately a test of how understandable the service portfolio is in relation to typical problems an architect might encounter.

Conclusion

In terms of intellectual challenge I’d say that working with either platform as an architect is roughly the same. But AWS has more to learn, and more irregularity, which means it takes longer, so if asked which certification is ‘harder’ I’d have to say AWS.

Notes

[1] I know that I’ve previously stated that I’m not a fan of learning from videos, but Scott’s course might be the exception to that. It was wonderfully dense, and I also appreciated being able to learn on the move with my iPad.

[2] Subsequently I found myself dearly wishing I’d been just a bit worse at French, which would have led to me doing Spanish ‘O’ Level, which I might just have passed – I failed French (not helped by a combination of dyslexia and negative marking for spelling mistakes).

[3] Of course I come at this with the benefit of being a native English speaker, and so the even worse irregularity of English is largely hidden to me, because I never had to learn it that way.

Filed under: cloud | 1 Comment

Tags: amazon, Associate, aws, certification, cloud, CSA, GCP, google, PCA, Pro

What are Modern Applications?

TL;DR

Modern Apps use Platforms, Continuous Delivery, and Modern Languages.

Or more specifically, Modern Apps are written in Modern Languages, get deployed onto Platforms, and that deployment process is Continuous Delivery (as these things are all interconnected).

Background

‘Modern Apps’ seems to be a hot topic right now. Some of my DXC colleagues are getting together for a workshop on Modern Apps next week (and this will be pre-read material). Our partner VMware launched its Modern Applications Platform Business Unit (MAPBU) this week, which brings together its acquisitions of Heptio and Pivotal. But it seems that many people aren’t too clear about what a Modern App actually is – hence this post.

Modern Apps use Platforms

Modern Apps are packaged to run on platforms; and the packaging piece is very important – it expresses a way by which the application and its dependencies are brought together, and it expresses a way by which the application and its dependencies can be updated over time to deal with functional improvements, security vulnerabilities etc.

It seems that the industry has settled on two directions for platforms – cloud provider native (and/)or Kubernetes:

Cloud Provider Native

‘Cloud Native’ is a term that’s become overloaded (thanks to the Cloud Native Compute Foundation [CNCF] – home of Kubernetes and its many members); so in this case I’m adding ‘Provider'[0] to mean the services that are native to public cloud providers – AWS, Azure, GCP.

And mostly not just running VMs as part of the Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS). For sure it’s possible to build a platform on top of IaaS (hello Netflix and Elastic Beanstalk etc.).

And not just the compute services, but also the state management services, whether that’s for more traditional relational databases, or more modern ‘NoSQL’ approaches whether that means key-value stores, document or graph databases, or something else.

The use of cloud native also implies that apps are composed from a set of loosely coupled services that connect together through their Application Programmer Interfaces (APIs). In general we can also expect an app (or group of apps working on the same data) to run on a single cloud provider, because of the economics of data gravity.

Kubernetes

In just over 5 years since its launch at the first DockerCon it seems safe now to say that Kubernetes has won out over the panoply of other platforms. Mesos, Docker Swarm and Cloud Foundry all took their swing but didn’t quite land their punch.

There’s definitely some overlap between Kubernetes and Cloud Native as defined above (particularly in Google’s cloud, where arguable they’ve been using Kubernetes as an open source weapon against AWS’s dominance in VM based IaaS). But in general it seems people choose Kubernetes (rather than cloud native) for its portability and a sense that portability helps avoid lock in[1].

Portability means that something packaged up to run on Kubernetes can run in any cloud, but it can also run on premises. For those who determine that they can’t use public cloud (for whatever reasons) Kubernetes is the way that they get the cloudiest experience possible without actual cloud.

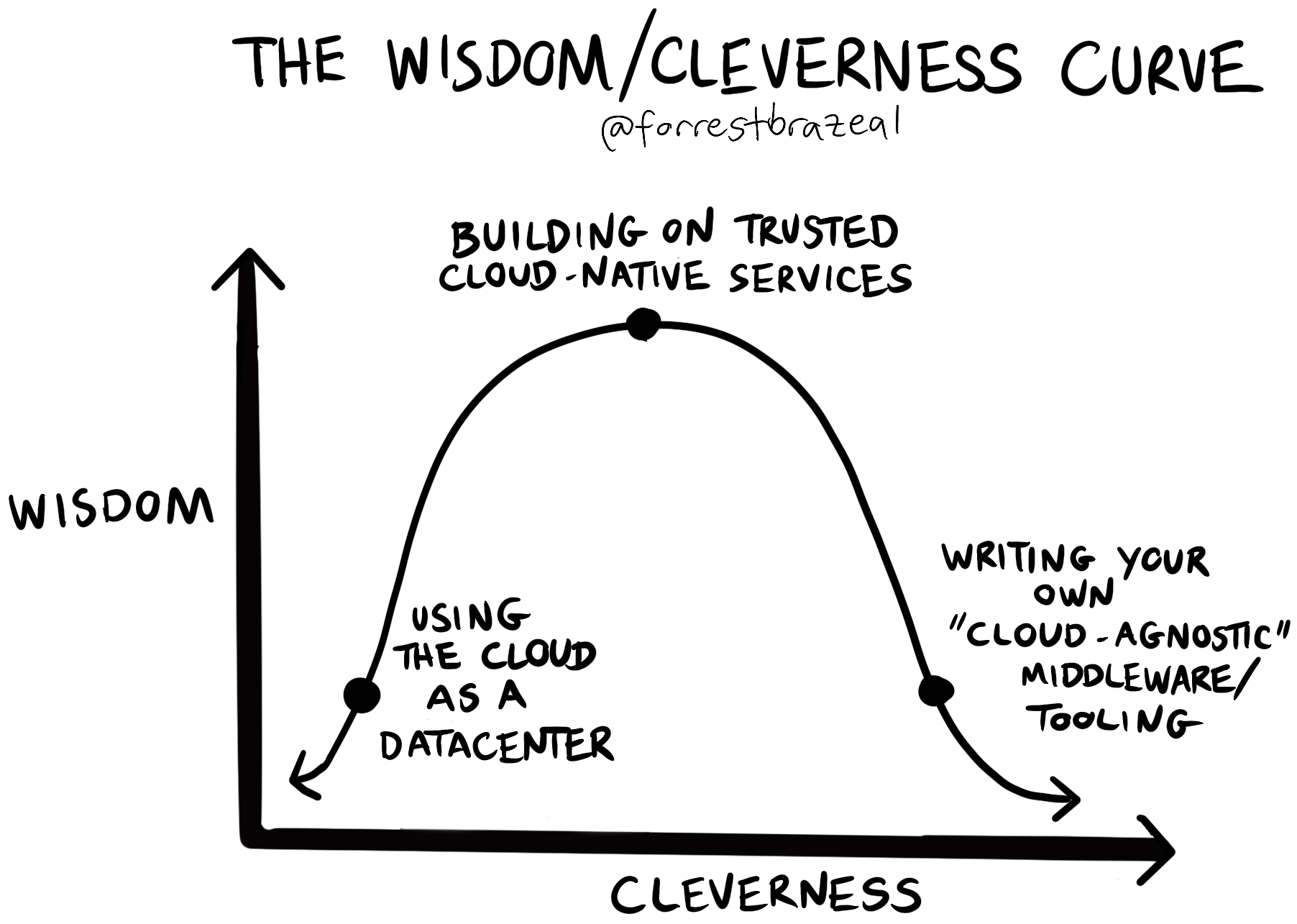

There’s a lot of scope for internal platform engineering teams to get themselves into trouble building something out of Kubernetes (which is addressed very well by Forrest Brazeal in his ‘Code-wise, cloud-foolish‘ post), but I’m expecting VMware (with Tanzu) and Google (with Anthos)[2] to take care of that stuff so that enterprises don’t have to.

Modern Apps use Continuous Delivery

Or maybe even Continuous Deployment, but mostly Continuous Delivery (CD), because not many organisations aren’t ready yet to have code changes flow all the way into production without at least one manual step.

CD pipelines provide a connective tissue between ever changing user need, and the platforms that apps are deployed onto.

CD pipelines also embody the tests necessary to validate that an application is ready for a production environment. For that reason Modern Apps are likely to be written using techniques such as Test-driven Development (TDD) and Behaviour-driven Development (BDD).

Of course there will be times where the test suite is passed and things make their way into production that shouldn’t, which is a good reason to make use of Progressive Delivery techniques and Observability.

Continuous Delivery implies DevOps

Pipelines run across the traditional Dev:Ops lines within an organisation, so running Modern Apps mean going through organisational change. DevOps Topologies does a great job of illustrating that patterns that work (and the anti-patterns that don’t).

It’s no accident that the operational practices of Site Reliability Engineering (SRE) evolved within Google at the same time as they were building and moving to their Borg Platform.

Modern Apps use Modern Languages

Or at least modern frameworks for some of the older languages – there’s a whole ton of Java still being written, but there’s a world of difference between the Enterprise JavaBean (EJB) centric world of Java 2 Enterprise Edition (J2EE) and today’s Spring Boot apps.

The RedMonk Programming Language Rankings (June 2019 edn) provide a good guide, if you can ignore C++, C and Objective-C, as popularity doesn’t equate to modernity. There’s also the Programming languages InfoQ Trends Report (October 2019 edn), which charts languages on a maturity curve:

and might be polyglot

Monolithic apps imply a single language; but the rise of microservices architecture comes about in part by empowering developers to choose the right languages and frameworks for their piece of the overall puzzle.

but doesn’t have to use a Microservice architecture

‘Microservices are for scaling your engineering organisation, not your app’ is how Microservices pioneer Adrian Cockcroft puts it, which is one of the reasons why Microservices is not a defining feature of Modern Apps.

It’s perfectly OK to have a small monolith developed by a small team if that’s all it takes to satisfy the business need. Per John Gall:

A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked. A complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be patched up to make it work. You have to start over, beginning with a working simple system.

A service provider view

Most of the discussion on apps centres on in house development, and the notion of ‘you wrote it, you run it’ is central to the operations philosophy within many organisations.

But looking at the application portfolio of most DXC customers there’s typically very few in house applications (and hence not very much ‘you wrote it, you run it’).

For sure there’s a bunch of apps that service providers like DXC (and Luxoft) and our competitors build (and run); but there’s also a ton of packaged apps (aka commercial off-the-shelf – COTS) that we run the infrastructure for.

There’s been a general shift away from on premises packaged apps to SaaS for CRM (e.g. Siebel to Salesforce), HR (e.g. Peoplesoft to Workday) etc. But there are still the cloud refusniks, and there are still many Independent Software Vendors (ISVs) selling stuff into the mass market and down to various niches. Just as virtualisation drove a shift from scripted installers to virtual appliances, we can expect to see another shift towards packaging for Kubernetes.

As we look forward to a world more defined by Application Intimacy, the work of service providers will be less about running the infrastructure (which is subsumed by the platforms), and more about care and feeding of the apps running on those platforms.

Bonus content

Platform History

Both Cloud Foundry and Kubernetes trace their roots back to Google and its Borg platform.

Cloud Foundry came from Xooglers Derek Collison and Mark Lucovsky during their time at VMware (before it was spun off into Pivotal), and the BOSH tool at its heart is a homage to Borg (BOSH == borg++).

Meanwhile Kubernetes came from within Google as a way of taking a Borg like approach to resource management applied to Linux containers that had been popularised and made accessible by Docker (which built on the work the Googlers had put into the Linux kernel as cGroups, Kernel capabilities and Namespaces on the way to making Linux and Borg what they needed).

It’s therefore well worth watching John Wilkes’ ‘Cluster Management at Google‘ as he explains how they manage their own platform, which gives insight into the platforms now available to the rest of us.

Of course platforms existed long before Borg, and the High Performance Computing (HPC) world was using things like the Message Passing Interface (MPI) prior to the advent of commercial grid computing middleware. What changed in the last decade or so has been the ability to mix compute intensive workload with general purpose (typically more memory intensive) workload on the same platform.

Heroku deserves a mention here, as one of the early popular Platforms as a Service (PaaS). The simplicity of its developer experience (DX) has proven to be an inspiration for much that’s happened with platforms since.

12 Factor

Modern Apps probably should be Twelve-Factor Apps:

- Codebase One codebase tracked in revision control, many deploys

- Dependencies Explicitly declare and isolate dependencies

- Config Store config in the environment

- Backing services Treat backing services as attached resources

- Build, release, run Strictly separate build and run stages

- Processes Execute the app as one or more stateless processes

- Port binding Export services via port binding

- Concurrency Scale out via the process model

- Disposability Maximize robustness with fast startup and graceful shutdown

- Dev/prod parity Keep development, staging, and production as similar as possible

- Logs Treat logs as event streams

- Admin processes Run admin/management tasks as one-off processes

But let’s just acknowledge that the 12 Factors might be aspirational rather than mandatory for many Modern Apps in real world usage.

HTTP or messaging based?

The web has made the HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP), and its more secure version HTTPS ubiquitous, especially as most firewalls have been configured to allow the easy passage of HTTP(S).

But HTTP is synchronous, and unreliable, which makes it a terrible way of joining things together.

Developers now have a bunch of choices for asynchronous (and sometimes reliable) messaging with protocols like AMQP, MQTT, NATS[3] and implementations such as RabbitMQ and Apache Kafka.

REST

The uphill battle here for messaging is that in the wake of heavy weight Service Oriented Architecture (SOA) defined by protocols like SOAP and WSDL, respresentational state transfer (REST) became the de-facto way of describing the APIs that connect things together, and it’s very tightly bound to HTTP methods.

Notes

[0] Thanks to my colleague Eric Moore for providing the suggestion of ‘Cloud Provider Native’ as a better label than just ‘Cloud Native’ (see thread on LinkedIn for background).

[1] Some wise words on this topic from OpenStack pioneer Randy Bias ‘You Are Locked In … Deal With It!‘ and from Gregor Hohpe on Martin Fowler’s blog ‘Don’t get locked up into avoiding lock-in‘ that now seem to have found their way into UK government guidance – ‘Managing technical lock-in in the cloud‘

[2] See Kubernetes and the 3 stage tech maturity model for more background

[3] Derek Collison pops up here again, as NATS came from his efforts at Apcera to build a better enterprise PaaS than Cloud Foundry. Collison has deep experience in the messaging space, having worked on TIBCO Rendevous and later their Enterprise Message Service (EMS), which he reflects on along with the origins of Cloud Foundry in this Twitter thread.

Filed under: architecture, cloud, DXC blogs, Kubernetes, technology | 2 Comments

Tags: 12 Factor, app, application, Borg, BOSH, CD, cloud, Cloud Foundry, cloud native, DXC, google, Kubernetes, modern, native, paas, platform

Andrew “bunnie” Huang recently presented at the 36th Chaos Communication Congress (36C3) on ‘Open Source is Insufficient to Solve Trust Problems in Hardware‘ with an accompanying blog post ‘Can We Build Trustable Hardware?‘. His central point is that Time-of-Check to Time-of-Use (TOCTOU) is very different for hardware versus software, and so open source is less helpful in mitigating the array of potential attacks in the threat model. Huang closes by presenting Betrusted, a secure hardware platform for private key storage that he’s been working on, and examining the user verification mechanisms that have been used in its design.

Filed under: InfoQ news, security | Leave a Comment

Tags: FPGA, hardware, open source, trust

TL;DR

We can model data gravity by looking at the respective storage and network costs for different scenarios where workload and associated data might be placed in one or more clouds. As network egress charges are relatively high, this makes the effect of data gravity substantial – pushing workloads and their data to be co-resident on the same cloud.

Background

Dave McCrory first proposed the idea of Data Gravity in his 2010 blog post ‘Data Gravity – in the Clouds‘:

Consider Data as if it were a Planet or other object with sufficient mass. As Data accumulates (builds mass) there is a greater likelihood that additional Services and Applications will be attracted to this data

He finishes the post with ‘There is a formula in this somewhere’. This post will attempt to bring out that formula.

More recently

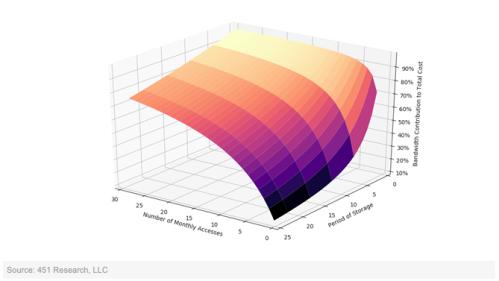

The 451 Group’s cloud economist Owen Rogers wrote a report almost a year ago titled ‘The cloud bandwidth tax punishes those focused on the short term’ (paywalled), where he explored the interactions between storage cost and bandwidth cost.

As I noted in The great bandwidth swindle cloud providers are using egress charges as an economic moat around their services. It makes data gravity true.

Owen’s report contains a simple model charting access frequency against storage period to determine a heat map of bandwidth contribution to total cost, and it’s a very hot map, with much of the surface area past 50%.

With thanks to Owen Rogers at The 451 Group for allowing me to use his chart

The emerging message is simple – once your data is in a cloud storage is very cheap relative to the cost of getting the data back out.

The corollary is also alluringly simple – data gravity is real, so you should put all of your data (and associated workload) into the same cloud provider.

Variables

We typically refer to compute, storage, and network when talking about systems, so let’s use the variables c, s, and n respectively.

Duration

c is usually billed by the hour, though the resolution on usage might be down to the second for IaaS or by a number of invocations for FaaS (with CaaS and PaaS dropping somewhere in between on the spectrum).

s is usually billed by the GB/month

n is usually billed by the GB

Most clouds present bills on a monthly basis, so it makes sense to evaluate over that duration, and allows us to build realistic scenarios of how c, s & n combine to a total bill (b).

The basic equation

b = c + s + n

Simple enough, the monthly bill is the sum of compute, storage and network egress costs, which is pretty uninteresting.

Two clouds

This is where it gets interesting. It could be two regions in the same cloud provider, two different cloud providers, or the oft discussed hybrid of a public cloud and a private cloud. The gross mechanics are the same, but the scaling factors may vary a little.

b = c1 + s1 + n1 + c2 + s2 + n2

Again, this seems simple enough – the monthly bill is just the sum of compute, storage and network egress used across the two clouds.

Base case – independent applications

Where the apps deployed into cloud 1 and cloud 2 have no interaction there’s really nothing to consider in terms of the equation above. We can freely pick the clouds for reasons beside data gravity.

Case 1 – monthly data copy

Scenario – the transactional app in cloud1 generates 100GB of data each month that needs to be copied to the reporting app in cloud2

Assumption 1 – compute costs are roughly equivalent in cloud1 and cloud2, so we’ll ignore c1 and c2 for the time being, though this will give food for thought on what the delta between c1 and c2 needs to be to make it worth moving the data.

Assumption 2 – the output from the reporting app is negligible so we don’t run up egress charges on cloud2

Assumption 3 – once data is transferred to the reporting app it can be aged out of the transactional app’s environment, but the data is allowed to accumulate in the reporting app, so the storage cost goes up month by month.

Taking a look over a year:

b1 = $2.5 + $9 + $2.5 +0

b2 = $2.5 + $9 + $5 +0

b3 = $2.5 + $9 + $7.5 +0

b4 = $2.5 + $9 + $10 +0

b5 = $2.5 + $9 + $12.5 +0

b6 = $2.5 + $9 + $15 +0

b7 = $2.5 + $9 + $17.5 +0

b8 = $2.5 + $9 + $20 +0

b9 = $2.5 + $9 + $22.5 +0

b10 =$ 2.5 + $9 + $25 +0

b11 = $2.5 + $9 + $27.5 +0

b12 = $2.5 + $9 + $30 +0

by = 12 * $2.5 + 12 * $9 + 12 * ((12 + 1) / 2) * $2.5 = $30 + $180 + $195 = $405

In this case the total storage cost is $225 and the total network cost is $180, so network is 44% of the total.

Refactoring the app so that both transactional and reporting elements are in the (same region of the) same cloud would save the $180 network charges and save that 44% – data gravity at work.

Case 2 – daily data copy (low data retention)

Scenario – the modelling app in cloud1 generates 100GB of data each day that needs to be copied to the reporting app in cloud2

Assumptions 1 & 2 hold the same as above

Assumption 3 – the reporting app updates a rolling underlying data set

b = $2.5 + $270 + $2.5 + 0

by = 12 * $2.5 + 12 * $270 + 12 * $2.5 = $30 + $3240 + $30 = $3300

In this case the total storage cost is $60 and the total network cost is $3240, so network is 98% of the total. The Data Gravity is strong here.

Case 3 – daily data copy (high data retention)

Scenario – the modelling app in cloud1 generates 100GB of data each day that needs to be copied to the reporting app in cloud2

Assumptions 1 & 2 hold the same as above

Assumption 3 – the reporting app keeps all data sent from the modelling app

b1 = $2.5 + $270 + $37.5 + 0

…

b12 = $2.5 + $270 + $862.5 + 0

by = 12 * $2.5 + 12 * $270 + 12 * 30 * (12 / 2) * $2.5 = $30 + $3240 + $5400 = $8670

In this case the total storage cost is $5430 and the total network cost is $3240, so network is down to 37% of the total, which is still pretty strong data gravity.

Conclusion

We can build an economic model for data gravity, and it seems to be sufficiently non trivial to lead to billing driven architecture, at least for a handful of contrived use cases. Your mileage may vary for real world uses cases, but they’re worth modelling out (and I’d love to hear the high level findings people have in comments below).

Filed under: cloud | 2 Comments

Tags: cloud, data, economics, equation, formula, gravity