Green Earl Grey

A few years ago I accidentally gave up coffee. It wasn’t pleasant at the time, but I felt much better afterwards, so I stuck with it. I still enjoy a very occasional double espresso, and caffeine is a wonderful thing when it’s not part of a regular habit or dependency.

When I returned from the holiday that led to me giving up coffee Twinings had just launched their new range of Green Teas, and frequently gave away samples at London Bridge and Canary Wharf stations – so some mornings I got two samples. I quickly discovered that a cup of green tea made for a good start for the day. The pineapple and grapefruit mix was an early favourite, but then I discovered the Green and Earl Grey and I had a new daily cuppa.

Initially I had no problem getting this blend, as the launch promotion reached into most major supermarkets and I could pick it up off the shelf. Then I found myself having to make a special trip to the big Tesco in the next town, and then I found myself having to order direct from the Twinings online store. I used to order a lot in one go (normally the best part of a years supply) in order to get free shipping.

To my horror I discovered earlier this year that Twinings had discontinued the line (not long after I’d made my last order). I wish they’d emailed to say so in advance – I’d have probably bought a huge stockpile – tea doesn’t seem to go off.

Whilst I kept hoping to stumble across a hidden away stash my supplies dwindled, and I found myself trying out alternatives…

Green on its own is too boring.

A bit of green and a bit of Earl Grey in the same cup comes out with too much black tea flavour.

I even tried flavouring some green tea bags with Bergamot oil following some instructions I found on Reddit, but it came out with too much of a bitter after taste.

and then I found my salvation.

Taylors of Harrogate (the tea brand that goes with the famous Betty’s tea rooms that was a fixture of my University days in York) has a Green Earl Grey blend.

It’s a bit more floral than the Twinings, and I suspect it’s a bit more sensitive to water temperature (add some cold first to avoid bitter after taste), but after about a month I’m happily switched over.

Fingers crossed that they’re still doing it when I finish the 350 bags I got in my first order.

Filed under: review, wibble | Leave a Comment

Tags: Bergamot, Bettys, Earl Grey, green, Taylors, tea, Twinings

Review – BeagleBone Black

I first came across the BeagleBone when Roger Monk presented at OSHUG #18 in April 2012. It was easy at the time to write it off as too expensive and too underpowered – the Raspberry Pi was finally shipping and the lucky first 2000 already had their $35 computers whilst the rest of us waited for the next batch to roll out of the factories. Who in their right minds would spend three times more on something less capable?

Things change quickly in the tech world, and the BeagleBone Black seems to have resolved issues with both price and capability. It’s impossible to avoid comparisons with the Raspberry Pi, so I won’t even try:

| Raspberry Pi Model B | BeagleBone Black | |

| MSRP | $35 | $45 |

| I paid | £23.39 | £25.08 |

| Processor | 700Mhz ARMv6 | 1Ghz ARMv7-A |

| RAM | 512MB SDRAM | 512MB DDR3 |

| Onboard flash | None | 2GB |

| External flash | SD | microSD |

| Network | 100Mb | 100Mb |

| USB ports | 2 | 1* |

| Video out | HDMI/Composite | microHDMI |

| Audio out | HDMI/3.5mm | microHDMI |

| Resolution | 1920×1080 | 1280×1024 |

| GPIO ports | 17 | 65 |

The comparison could go on further, but I’ll try to concentrate on the main differences…

CPU

The BeagleBone Black’s CPU is faster by clock speed and a more modern design. This means that it can run Ubuntu rather than needing it’s own flavour of Linux. That probably isn’t much of a big deal now that Raspbian is so popular, and it’s a rare day when I notice I’m using Raspbian rather than Ubuntu (in fact Raspbian feels more like Ubuntu than Debian for the tools I regularly use).

BeagleBone Black 1 : Raspberry Pi 0

Storage

The BeagleBone comes with 2GB of onboard flash, which means that there’s no need to buy an SD card to get it going. Better still it comes pre installed with Angstrom Linux, a web IDE and a node.js environment for controlling GPIO. There’s further expansion via microSD and given that there’s little spread on price or performance these days between SD and microSD that’s a good thing as the form factor is tidier.

BeagleBone Black 2 : Raspberry Pi 0

Video

Eben Upton often talks about the Raspberry Pi using a mobile phone system on chip (SOC), but I suspect that it might actually be a part designed for set top boxes (there are after all very few mobile phones with full HD screens). Not only can the Pi drive a screen at 1920×1080, but it also has hardware acceleration for popular video CODECs. The original BeagleBone was missing video altogether (it needed a ‘cape’), so it’s a big move forward that the Black can drive a screen, and 1280×1024 is fine for many purposes – it just doesn’t suit modern wide screen monitors, and it’s not much use for home entertainment purposes.

BeagleBone Black 2 : Raspberry Pi 1

USB

The twin USB port on the raspberry Pi means that it’s easy to connect a keyboard and mouse, or a keymote and a WiFi dongle. I know that many people use their Pis with (powered) USB hubs, but I so far seem to have got away without needing to do that. Sadly the BeagleBone Black has only 1 USB port, so it’s pretty hard to use USB peripherals without resorting to a hub. Given that there’s an Ethernet connector that’s the same height as a double USB port at the other end of the board it seems rather silly to have cut this corner.

BeagleBone Black 2 : Raspberry Pi 2

The BeagleBone Black has some other USB tricks up its sleeve though… Like the Raspberry Pi it takes power from a USB connector (mini rather than micro), but unlike the Pi it’s designed to connect to another computer (as the power draw is within normal USB range). In addition to using this port for power the BeagleBone can also use it as a virtual network port, so all that’s needed to start playing with the BeagleBone is what comes in the box and a regular laptop or computer.

BeagleBone Black 3 : Raspberry Pi 2

GPIO

Not long after my kids first got their hands on a Pi I realised that they weren’t interested in low powered computers (they already have better) or cheap computers (they don’t pay for them). They were however interested in physical compute projects – anything that could interact with the outside world… and that meant doing stuff with general purpose input output (GPIO).

We’ve had lots of fun flashing LEDs, building burglar alarms and playing ladder game, and all this stuff was made possible by the Pi’s GPIO. I’ve not yet exhausted the Pi’s GPIO capabilities with any project, but it wouldn’t be too hard – though there’s always I2C and SPI there to expand things. I’ve also found it reasonably easy to work with breadboard projects using a ‘Pi Cobbler‘ or build my own things using boards like Ciseco’s ‘Slice of Pi‘.

The Pi might be good for GPIO, but the BeagleBone is great for it. With 65 GPIO ports, and nice chunky ports down both sides (perfect for poking components or jump wires straight in).

BeagleBone Black 4 : Raspberry Pi 2

Projects

I thought I’d reflect back over the projects that I’ve used my Pis for over the past year or so:

- OpenELEC (living room media streaming) – whilst I expect it wouldn’t be too hard to port OpenELEC to the BeagleBone Black it’s weaker graphics capabilities mean that I can’t really see the point.

- iPad connectivity – the BeagleBone would be just fine at running VNC.

- Securely accessing your home network – the key requirements here are SSH and low power consumption, so the BeagleBone Black is great.

- Alarm – the better GPIO on the BeagleBone would have made this very easy (and possibly it could have all been done in the integrated IDE).

- Arcade Gaming – porting MAME should be straightforward. The video limitations won’t matter for older games, and the better CPU might make some games work better that struggle on the Pi. Hooking up a joystick via GPIO should be easy.

- Project boards – there’s less need for project boards with BeagleBoard given it’s better GPIO capabilities, and the stackable ‘capes’ offer lots of very tidy ways to expand.

- Sous Vide – this would be an easy project on the BeagleBoard, though I ended up using a Model A Raspberry Pi for this (which would still be a bit cheaper).

Conclusion

For me the Raspberry Pi has excelled at two things:

- It’s a great low cost streaming media player when paired with OpenELEC (or similar XBMC distro)

- It’s great for physical compute projects

The BeagleBone Black doesn’t have the media capabilities of the Pi, but it’s even better that the Pi for physical compute projects. Despite that I’d be surprised if the BeagleBone enjoys the same success in terms of community mind share and volume shipped. Of course that doesn’t matter… the improvement of the Black over the original BeagleBone shows that we can expect a much better/cheaper Raspberry Pi some time in the not too distant future.

Filed under: BeagleBone, Raspberry Pi, review | 3 Comments

Tags: BeagleBone, BeagleBone Black, comparison, GPIO, physical compute, projects, Raspberry Pi, raspbian, review, Ubuntu

Shiva Iyer at Packt Publishing kindly sent me a review copy of Instant OpenELEC Starter. It’s an ebook with a list price of £5.99, and I was able to download .pdf and .mobi versions (with an .epub option too). It’s also available from Amazon as a paperback (£12.99) and for Kindle (£6.17).

The book is pretty short, with a table of contents that runs to 35 pages, and it’s set at an introductory level that seems intended for new users of OpenELEC and XBMC.

It breaks down roughly into thirds:

- Installation (with instructions for PC and Raspberry Pi).

- Managing XBMC – the basics of creating content libraries for various media.

- Top 10 features – some slightly more advanced customisations.

If you’re after a detailed explanation of what OpenELEC is, and how it’s put together then you’ll need to look elsewhere.

I could pick holes in some of the details of the Raspberry Pi install guide, but the information is accurate enough. Overall the author, Mikkel Viager, has done a good job of explaining what’s required and how to do things.

Filed under: Raspberry Pi, review | Leave a Comment

Tags: ebook, openelec, Raspberry Pi, Raspi, review, RPi, XBMC

A well regulated lobby

Our elected (and unelected) officials keep getting caught with their hands in the till by investigative journalists.

The proposed remedy for this is to establish a register for lobbyists. A plan that the Chartered Institute of Public Relations (CIPR) seems to be eagerly embracing (when it’s not saying that the plan needs to be even more encompassing). I smell a rat. It’s just not normal for people to ask for more regulation of their industry, unless they have (or are trying to establish) regulatory capture.

Why politicians like the idea

A register of lobbyists will make it easy for politicians to check the credentials of those they’re speaking to. This will make it harder (more expensive and time consuming) for investigative journalists to pose as lobbyists. Newspapers are now going to have to run cut out lobby organisations (on a variety of issues to suit the needs of future stings). This will likely preclude public interest broadcasters like the BBC from participation – building fake lobby organisations won’t be seen as a good use of TV license payer’s money.

So this is all about stopping politicians from getting caught, and does nothing to stop politicians from being corrupt (and of course even the non corrupt politicians don’t like people getting caught, because it makes their parties and the entire political establishment look bad).

Why the professional lobbyists like the idea

A register will be a barrier to entry. Their job is to gain access to people with limited time and bandwidth, so anything that cuts down the size of the field helps.

Why ordinary citizens should not like the idea

If the only lobbyists are professional lobbyists then our political system becomes entirely bought and paid for[1]. Amateur lobbyists and pressure groups are an essential part of the democratic process. As Tim Wu pointed out in his ORGCon keynote at the weekend – movements start with the amateurs and enthusiasts.

I was personally involved in the creation of The Coalition For a Digital Economy (Coadec) at a time when the Digital Economy Bill (now Act) was threatening to undermine the use of the Internet by many small businesses. That organisation is now well enough established that I’m sure it could step in line with any regulation of lobbyists. It’s hard to see how we’d have got from a bunch of geeks in a Holborn pub to what’s there today without the support of friendly politicians. We needed access, and regulation would be just another barrier to that access.

Conclusion

Regulating lobbyists will not prevent corruption in politics. Quite the opposite – it will make it more challenging for individual corruption to be found out, and strengthen the systemic corruption of corporate interests in politics. We all ought to get lobbying about this while we still can.

Notes

[1] Rather than mostly bought an paid for as it is today.

Filed under: politics | Leave a Comment

Tags: citizen, corruption, lobby, politician, politics, regulation

Indistinguishable from fraud

I came across this tweet yesterday:

It was timely, as I was in the midst of sorting out a foreign exchange transaction that had gone wrong. I’d sent $250 to a recipient in the US, and only $230 had shown up in their account (and then their bank had charged them $12 for the privilege of receiving it). Somehow $20 had gone missing along the way.

The payments company had this to say on the matter:

I would also not be happy if $20 was missing from a transfer and I apologise for the situation.

This does, unfortunately, happen from time to time. Normally it is a corresponding bank charge charged en route, which we will refund.

I responded:

Whilst your explanation might fit something off the beaten path there’s no good reason for $20 to vanish into the ether on a well worn road like GBP/USD. My first guess would be somebody fat fingered this at some manual data entry stage (I’d like to hope that you have a straight through process, but I expect it isn’t), my second guess would be fraud.

and they’d said in return:

I assure you that our instruction was for the full amount and there is no fraudulent activity.

At the moment our payments to the USA are via the SWIFT network and as they are international cross border payments there can be correspondent banks involved that we have no control over.

So there we have it – some random correspondent bank along the payment chain treating itself to $20 is completely fine – that’s not fraud. Or maybe two banks helped themselves to $10 each? Nobody seem to know, and nobody seems to care – cost of doing business.

I wouldn’t call out international payments and foreign exchange (FX) as being ‘advanced financial instruments’, but I do know that it’s mostly a disgraceful shambles. If I add up the total fees, charges and spreads associated with this simple transaction then it comes out at almost $50, or around 20% of my transaction. That’s just utterly ridiculous for squirting a few bits from a computer in the UK to a computer in the US. It makes what the telcos charge for SMS seem reasonable (which it is not).

It’s no wonder that developing economies, and particularly small firms within developing economies, are struggling to engage in international commerce. If it’s this hard and expensive to move money along what should be the trunk road of UK/US then I dread to think what it’s like trying to do business off the beaten path (such as to or from Sub-Saharan Africa). I’m pleased to see that the World Bank is doing something about this by investing in payments companies that route around some of the greedy mouths to feed by taking advantage of low cost national payments networks (like ACH in the US, Faster Payments in the UK and corresponding systems elsewhere). Of course SWIFT still gets their pound of flesh (for the time being), but perhaps as we get better netting over that network the toll will be minimised.

Filed under: could_do_better, grumble | 3 Comments

Tags: banking, charges, fees, financial services, fraud, FX, international, payments, spreads

OpenELEC dev builds

Over the past week or so my automated build engine for OpenELEC on the Raspberry Pi hasn’t been working. XBMC has grown to a point where it will no longer build on a machine with 1GB RAM.

Normal services has now been resumed, as the good people at GreenQloud kindly increased my VM from t1.milli (1 CPU 1GB RAM) to m1.small (2 CPUs 2GB RAM). In fact I’m hoping that the extra CPU might even make the build process quicker. I have to congratulate the GreenQloud team for how easy the upgrade process was – about 3 clicks followed by a reboot of the VM. Not only are they the most environmentally friendly Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS), but also one of the easiest to use – thanks guys.

Filed under: cloud, Raspberry Pi | Leave a Comment

Tags: cloud, GreenQloud, iaas, openelec, Raspberry Pi, Raspi, RPi, XBMC

Magic teabags

I’m a creature of habit, and like a cup of green and Earl Grey[1] to start my day and a Red Bush (aka Rooibos) mid afternoon. Approximately nowhere that I go has the tea that I like to drink, so I take along my own stash. This means that I often find myself asking for a cup of hot water when those around me are ordering their teas and coffees, and 99% of the time that isn’t a problem. I sometimes feel like a bit of a cheapskate in high street coffee shops, but then I think of Starbucks and their taxes and the guilt subsides.

My teabags are tasty but they’re not magic – they simply infuse hot water with a flavour I like.

easyJet sell magic teabags. For £2.50.

I have no idea what easyJet’s magic teabags taste like (and let’s face it, £2.50 is a lot for a cup of tea – they should taste great), but the magic is isn’t in the taste. It’s in their safety properties.

easyJet teabags turn otherwise dangerous cups of scalding water into perfectly safe cups of tea.

I know this because EasyJet cabin crew aren’t allowed to give me a cup of hot water any more for ‘health and safety reasons’, but they are allowed to sell me a cup of tea for £2.50. Since I asked really nicely they even sold me a cup of tea without putting the magic teabag in. I’ll assume that the magic works at a (short) distance – so it’s OK for me to have the teabag on the tray table in front of me, and not OK for it still to be on the cart making its way down the aisle.

I could accuse easyJet of perverting the cause of ‘health and safety’ to benefit their greed. In fact I did in a web survey I completed following a recent trip:

All I wanted was a cup of hot water (I carry my own tea bags as I prefer a type that is never available anywhere I go). This has never been a problem in the past on Easyjet flights, but this time the crew told me that they’re no longer allowed to serve hot water for ‘health and safety reasons’. Apparently a £2.50 teabag has the magical property of turning a cup of scaling water into something safe. The crew very kindly obliged my request to sell a cup of tea without the teabag being dunked. I got ripped off and nobody was made any safer. Blaming your corporate greed on health and safety isn’t a way to impress your customers.

I should point out that easyJet aren’t alone in this shameful practice, they’re just the first airline I’ve found doing it. I’ve also come across it at conference centres where ripoff prices are charged for beverages – Excel, Olympia and Earls Court I’m looking at you.

Maybe if I keep my magic teabag I can use it again on another flight. Or does it have some sort of charge that runs out?

Notes

[1] This is as good a place as any for me to say how disappointed I am that Twinings have discontinued their superb Green and Earl Grey blend. It still gets a mention on their web site, but they stopped selling it a year or so ago. Had I known I’d have bought more than a years supply when I last did a bulk order – of course (like most companies) they didn’t bother to tell me (their previously loyal customer) that they were going to stop making and selling something that I’d been buying regularly for years. I have yet to perfect my own blend of Green and Earl Grey.

Filed under: could_do_better, grumble | 3 Comments

Tags: EasyJet, heath and safety, hot water, magic, tea, tea bag, teabag

This post first appeared on the CohesiveFT blog.

One of the announcments that seemed to get lost in the noise at this week’s IO conference was that Google Compute Engine (GCE) is now available for everyone.

I took it for a quick test drive yesterday, and here are some of my thoughts about what I found.

Web interface

gcutil

Access control

Beware, Fluffy Cthulhu will eat your brains if you think you can just source different creds to switch between accounts

SSH

- gcutil creates a keypair and copies the private key to ~/.ssh/google_compute_engine

- the public key is uploaded to your project metadata as name:key_string

- new users of ‘name’ are created on instances in the project

- and the key_string is copied into ~/.ssh/authorized_keys on those instances

- meanwhile gcutil sits there for 5 minutes waiting for all that to finish

- I’ve found that the whole process is much faster than that, and in the time it takes me to convert a key to PuTTY format everything is ready for me to log into an instance (whilst gcutil is still sat there waiting).

Access control redux – multi accounts

Image management

Network

Disks

Speed

Price

I’m not so sure:

Paying for a whole hour when you tried something for a few minutes (and it didn’t work so start again) might be a big deal for people tinkering with the cloud. It might also be a thing for those bursty workloads, but I think for most users the integral of their minute-hour overrun is a small number (and Google will no doubt have run the numbers to know that exactly).

In effect per minute billing means GCE runs at a small discount to AWS for superficially similar price cards, but I don’t see this being a major differentiator. It’s also something that AWS (and other clouds) can easily replicate.

Conclusion

Filed under: cloud, CohesiveFT, review | Leave a Comment

Tags: access control, cloud, GCE, gcutil, google, iaas, identity, image management, network, performance, price, SSH, storage, UI, web

Authorization

In which I examine why XACML has failed to live up to my expectations, even if it isn’t dead, which has been the topic of a massive blogosphere battle in recent weeks.

Some background

I was working with the IT R&D team at Credit Suisse when we provided seed funding[1] for Securent, which was one of the first major XACML implementations. My colleague Mark Luppi and I had come across Rajiv Gupta and Sekhar Sarukkai when we’d been looking at Web Services Management platforms as their company Confluent had made our short list. The double acquisition by Confluent by Oblix then Oracle set Rajiv free, and he came to us saying ‘I’m going to do a new startup but I don’t know what it is yet’. Mark had come to the realisation that authorization was an ongoing problem for enterprise applications, and we suggested to Rajiv that he build an entitlements service, with us providing a large application as the proof point.

My expectations

Back in March 2008 (when I was still at Credit Suisse) I wrote ‘Directories 2.0‘ in which I laid out my hopes that XACML based authorization services would become as ubiquitous as LDAP directories (particularly Active Directory).

I also at that time highlighted an issue – XACML was ‘like LDIF without LDAP’ – that it was an interchange format without an interface. It was going to be hard for people to universally adopt XACML based systems unless there was a standard way to plug into them. Luckily this was fixed the following year by the release of an open XACML API (which I wrote about in ‘A good week for identity management‘).

I’ll reflect on why my expectations were ruined toward the end of the post.

Best practices for access control

Anil Saldhana has stepped up out of the idendity community internicine warfare about XACML and written an excellent post ‘Authorization (Access Control) Best Practices‘. I’d like to go through his points in turn and offer my own perspective:

- Know that you will need access control/authorization

The issue that drove us back at Credit Suisse was that we saw far too many apps where access control was an afterthought. A small part of the larger problem of security being a non functional requirement that’s easy to push down the priority list whilst ‘making the application work’. Time and time again we saw development teams getting stuck with audit points (a couple of years after going into production) because authorization was inadequate. We needed a systematic approach, an enterprise scale service, and that’s why we worked with the Securent guys. - Externalize the access control policy processing

The normal run of things was for apps to have authorization as a table in their database, and this usually ran into trouble around segregation of duties (and was often an administrative nightmare). - Understand the difference between coarse grained and fine grained authorization

This is why I’m a big fan of threat modeling at the design stage for an application, as it makes people think about the roles of users and the access that those roles will have. If you have a threat model then it’s usually pretty obvious what granularity you’re dealing with. - Design for coarse grained authorization but keep the design flexible for fine grained authorization

This particularly makes sense when the design is iterative (because you’re using agile methodologies). It may not be clear at the start that fine grained authorization is needed, but pretty much every app will need something coarse grained. - Know the difference between Access Control Lists and Access Control standards

We’re generally trying not to reinvent wheels, but this point is about using new well finished wheels rather than old wobbly ones. I think this point also tends to relate more to the management of unstructured data, where underlying systems offer a cornucopia of ACL systems that could be used. - Adopt Rule Based Access Control : view Access Control as Rules and Attributes

This relates back to the threat model I touched upon earlier. Roles are often the wrong unit of currency because they’re an arbitrary abstraction. Attributes are something you can be more definite about, as they can be measured or assigned. - Adopt REST Style Architecture when your situation demands scale and thus REST authorization standards

This is firstly a statement that REST has won out over SOAP in the battle of WS-(Death)Star, but is more broadly about being service oriented. The underbelly of this point is that authorization services become a dependency, often a critical one, so they need to be robust, and there needs to be a coherent plan to deal with failure. - Understand the difference between Enforcement versus Entitlement model

This relates very closely to my last point about dependency, and whether the entitlements system is an inline dependency or out of band.

So what went wrong?

It’s now over 5 years since I laid out my expectations, and it’s safe to say that my expectations haven’t been met. I think there are a few reasons why that happened:

- Loss of momentum

Prior to the Cisco acquisition Securent was one of a handful of startups making the running in the authorization space. After the acquisition the Securent stopped moving forward, and the competition didn’t have to keep running to keep up. The entire segment lost momentum. - My app, your apps

Entitlements is more of a problem for the enterprise with thousands of apps than it is for the packaged software vendor that may only have one. We ended up with a chicken and egg situation where enterprises didn’t have the service for off the shelf packages to integrate into, and since the off the shelf packages didn’t support entitlements services there was less incentive to buy in. Active Directory had its own killer app – the Windows Desktop, which (approximately) everybody needed anyway, and once AD was there it was natural to (re)use it for other things. Fine grained services never had their killer app – adoption always had to be predicated on in house apps. - Fine grained is a minority sport

Many apps can get by with coarse grained authorization (point 4 above) so fine grained services find it harder to build a business case for adoption. - In house can be good enough

When the commercial services aren’t delivering on feature requests (because the industry lost momentum), and the problem is mostly in house apps (because off the shelf stuff is going its own way) then an in house service (that isn’t standards based) might well take hold. Once there’s a good enough in house approach the business case of a 3rd party platform becomes harder than ever to make.

Conclusion

It’s been something like 9 years since I started out on my authorization journey, and whilst the state of the art has advanced substantially, the destination I envisaged still seems almost as distant as it was at the start. XACML and systems based upon it have failed to live up to my expectations, but that doesn’t mean that they’ve failed to deliver any value. I think at this point it’s probably fair to say that the original destination will never be reached, but as with many things the journey has bourne many of its own rewards.

Notes

[1] Stupidly we didn’t take any equity – the whole thing was structured as paying for a prototype

Filed under: identity, security | Leave a Comment

Tags: access control, ACL, authorisation, authorization, coarse grained, entitlements, fine grained, ldap, ldif, REST, Securent, service, SOA, SOAP, xacml

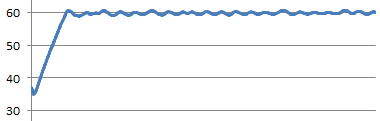

I’ve been very happy with the results from my Raspberry Pi controlled water bath for sous vide cooking, but I knew that the control loop could be improved. Past runs show fairly continued oscillation:

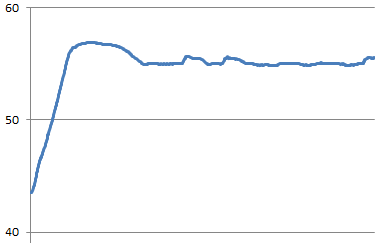

I’ve been keeping track of the average power for my control loop, which has been coming out at 22%. So i modified the code to have a bias of 22%, and here’s the result:

Overall much more stable. The occasional hiccups are probably caused by the remote socket failing to receive off commands. There’s a 3C overshoot at the start, which I hope to have fixed by entering the control loop from initial warm up 3C earlier. Here’s the new code (also available at GitHub):

import os

from subprocess import Popen, PIPE, call

from optparse import OptionParser

from time import sleep

def tempdata():

# Replace 28-000003ae0350 with the address of your DS18B20

pipe = Popen(["cat","/sys/bus/w1/devices/w1_bus_master1/28-000003ea0350/w1_slave"], stdout=PIPE)

result = pipe.communicate()[0]

result_list = result.split("=")

temp_mC = int(result_list[-1]) # temp in milliCelcius

return temp_mC

def setup_1wire():

os.system("sudo modprobe w1-gpio && sudo modprobe w1-therm")

def turn_on():

os.system("sudo ./strogonanoff_sender.py --channel 4 --button 1 --gpio 0 on")

def turn_off():

os.system("sudo ./strogonanoff_sender.py --channel 4 --button 1 --gpio 0 off")

#Get command line options

parser = OptionParser()

parser.add_option("-t", "--target", type = int, default = 55)

parser.add_option("-p", "--prop", type = int, default = 6)

parser.add_option("-i", "--integral", type = int, default = 2)

parser.add_option("-b", "--bias", type = int, default = 22)

(options, args) = parser.parse_args()

target = options.target * 1000

print ('Target temp is %d' % (options.target))

P = options.prop

I = options.integral

B = options.bias

# Initialise some variables for the control loop

interror = 0

pwr_cnt=1

pwr_tot=0

# Setup 1Wire for DS18B20

setup_1wire()

# Turn on for initial ramp up

state="on"

turn_on()

temperature=tempdata()

print("Initial temperature ramp up")

while (target - temperature > 6000):

sleep(15)

temperature=tempdata()

print(temperature)

print("Entering control loop")

while True:

temperature=tempdata()

print(temperature)

error = target - temperature

interror = interror + error

power = B + ((P * error) + ((I * interror)/100))/100

print power

# Make sure that if we should be off then we are

if (state=="off"):

turn_off()

# Long duration pulse width modulation

for x in range (1, 100):

if (power > x):

if (state=="off"):

state="on"

print("On")

turn_on()

else:

if (state=="on"):

state="off"

print("Off")

turn_off()

sleep(1)

Filed under: code, cooking, Raspberry Pi | 10 Comments

Tags: 434MHz, bias, control system, DS18B20, mains, PI, PID, python, Raspberry Pi, remote control, RPi, Sous vide, water bath