3 MiFi mini review redux

A little while ago I wrote about my 3 MiFi. To cut a long story short I wasn’t impressed, and rather wish that I had sent it back and got a refund. My mood wasn’t helped by the subsequent price drop of the PAYG package from £99 to £49 (albeit without 3 months of PAYG data that I didn’t need in the first place).

Crippled

It turns out that the device can actually do many of the things that I wanted it to do, it’s just that Three had crippled it. The main problem is the removal of the web interface (though there are rumours that Three may sanction a firmware update that will bring it back). The web interface presents options so that the MiFi can be ‘always on’ (as I think it should be when powered up).

Unlocking

It seems that DC-unlocker is now able to unlock the Huawei E5830, so for €15 you can use it on any network. I’ve also read various reports that Three will unlock a MiFi for £15, which seems pretty reasonable. Sadly the web interface lacks the ability to reconfigure APNs, so if you’re swapping SIMs around then you’ll need to use the WiFi Manager application.

Sadly PAYG SIMs that you might use when roaming seem to be no easier to get now than they were 6 months ago.

Upgrading Firmware

After getting my MiFi unlocked I was able to get at the web interface by doing a firmware update, following the instructions I found here. It was a hairy experience, and at one stage I thought I’d bricked the device. Luckily it has a maintenance mode that I found out about in this Chinenglish upgrade guide, which is entered by pressing and holding the mobile dial button then the power button for 5 seconds (after which the signal LED turns red and the battery LED turns yellow). After going into that maintenance mode I was able to get the firmware updater to talk to it again, and eventually managed a successful update. Huawei certainly have some work to do on their firmware update software to stop it from being so much like playing Russian roulette.

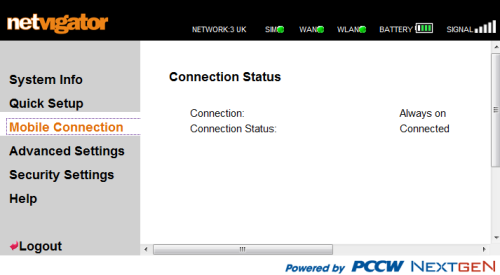

Web interface

The web interface is basic but functional. Having found the default username and password (admin/admin) I was able to get in and set it up so that it would establish a 3G/HSDPA data connection whenever powered on (which I still think should be the default). It works reasonably well on my iPod Touch as well as my netbook (at least on FireFox), making it easy to check on device status without having to physically poke and prod at it.

Residual concerns

Battery life is still a bit of an issue. It’s probably enough for my daily commute, but anything longer than that means you need USB power from somewhere (and the cable to hook it up).

I’m still not entirely convinced by the sensitivity of the antenna and receiver (which may just have an optimal orientation that I haven’t figured out yet). My sense right now is that it’s not quite as good as my Novatel XU870, but probably better than most USB dongles. I guess in the non commuting use case it has the advantage that you can place it where signal strength is best, which isn’t so easy with something attached to your laptop or whatever.

The 5 device limit for WiFi connections makes little sense to me. I get it that sharing a 3G connection with 5 laptops would probably be stretching things thin, but even on my commute I’d probably use it with 3 devices (netbook, iPod and BlackBerry) – so there’s not much to spare. A friend recently installed a MiFi in his rural house that suffers a lack of wired broadband. He’s very happy just to be online, and pleased that he often gets around 1Mb/s (sometimes a little more), but 5 devices goes quickly when you have a kids PC, a Wii, Nintendo DSIs, iPhones, netbooks etc. Of course most of these devices aren’t actually making use of the connection at any given time, but having to manually switch their WiFi on and off to keep within the connection limit will be a pain. I’ve suggested to my friend that he puts Windows 7 onto an old netbook and then uses Connectify to extend the WiFi bubble and work around the connection limit.

It’s still plasticky, though with the always on mode in action I can leave it in an old sunglasses bag and ignore the ugliness (and prevent scratches and other wear and tear).

For keeps

I’m well past being able to send it back, but with unlocked SIM capability and upgraded firmware that lets me do what I want with it I’m much happier with it. Happy enough that it will soon become my main means of mobile access as I ditch my old s10e netbook in favour of a new s10-3t ‘netvertible’ (which lacks the expresscard slot I need for my XU870).

Filed under: technology | 13 Comments

Tags: 3G, hotspot, mifi, mobile, review, wifi

iPod, eBook, dAllowance

‘Can I have an iPod Touch for my birthday?’ asked my five year old daughter yesterday (the birthday isn’t far away), ‘Susie has one, and she’s 6’. ‘No’, came my reply, ‘I gave you an iPod mini just a few weeks ago’. We’ve been going through a bit of an iPod upgrade cycle around the house since I filled up my old 1G Touch and decided to splash out on a newer 32GB model.

The physical kit is just the start of the problem though – what about content?

I was rather surprised to discover during my upgrade process that I didn’t have to rebuy my apps for my old iPod touch. It seems that the 5 ‘authorised’ machines that Apple allows me also translates to 5 devices worth of apps from a single account. To be honest I wouldn’t have minded buying Bejewelled 2 and Drop 7 again for my wife, as they’re only a couple of quid each.

Having a ‘family’ account for iTunes seems like a good plan (especially when it means that I don’t have to repeat buy the same stuff), but I sense trouble ahead…

- Firstly I’m not going to give my kids my iTunes password. Not only does it almost certainly break the terms of service (though why should I really care about that?), but it’s the digital equivalent of handing over an entire book of blank cheques. For similar reasons they also don’t get to have my eBay, Amazon or PayPal passwords (and I’ve started using two factor authentication for eBay and PayPal so that saved passwords don’t make my machine a soft target to work around this).

- Secondly what happens when they grow up and leave home? Do the mp3s that I bought for them (with my email address or some other identification almost certainly burnt into the metadata) have legal right of passage? When they are old enough to have a credit card and their own account will they be obliged to repurchase all of their old favourites? Will the ACTA empowered copyright goons at international borders be understanding when my daughter has married, but still carries content with her old the wrong name burnt into it?

- Thirdly I don’t always want to be the bottleneck on this stuff. If the kids want to spend their Christmas, birthday and pocket money on Hannah Montana mp3s, or Club Penguin or Moshi Monsters then I’d rather be out of the loop. If they wanted to buy the physical versions of these things (or even vouchers for some of the relevant services) then they can just walk into a shop and put cash on the counter.

What seems to be missing here is some sort of flexible electronic payments system for kids. Something that puts them in control of whatever allowance or gifts that they’re given (and let’s not forget that vouchers are like cash, only less good) – this needs to be better than cash, money that you can spend anywhere on the internet (that kids would go). Maybe when Rixty escapes from the US (and provided that it gets some broader adoption with the relevant services) it will be the thing? There is however a LOT going on in the payments world at the moment, particularly with prepaid debit, so plenty of scope for innovation and competition.

One potential spoiler is that many services (e.g. Amazon) insist on a credit card for digital products (presumably because the know you customer stuff that sits behind these products provides a stronger anchor to a given geography so that content distribution companies can play their stupid games with windows). Maybe those companies don’t see kids as an important market? Maybe they think that by pissing them off when they’re teenagers they’ll be all the more keen to buy their stuff when they’re ‘grown up’ and allowed proper plastic? Or maybe something new will come along and dis-intermediate these people back into the 20th century where their business model came from.

Filed under: media, technology | 3 Comments

Tags: allowance, amazon, credit card, debit card, ebay, ebook, ipod, itunes, money, payments, paypal, pocket money

eBooks and price discrimination

The weekend brought a bit of a storm over Amazon booting Macmillan off its platform, which has brought lots of worthy analysis from Charles Stross, Tim Bray and others.

Perhaps I’m missing something here, but it seems to me that the whole problem with eBooks is that they have only one dimension for price discrimination – time. For dead tree traditional books there tends to be a conflation of physical form discrimination (hardback versus paperback) and time discrimination (the hardback gets released first), but there’s loads of scope for making things very special indeed – author’s signed copies, custom bindings and more.

I’ve been frustrated in the past by having to buy a heavy hardcover when I want to get the latest release from one of my favourite authors. I’d have happily paid much the same cover price for the smaller lighter paperback. So maybe price discrimination on time only can be made to work for eBooks. But, the medium does constrain choice from a distribution point of view – as the eBook device owner has already chosen physical size and weight, what the outside looks like (a leather binding to fool airline stewardesses perhaps) etc. I also wonder if cover art is dead (removing some cost from the overall value chain, but also end of lifing a small creative channel)? It is clearly going to be hard to make a bunch of bits special.

This is a very different phenomenon versus what digitisation has done to the music industry, where the ‘1000 true fans‘ approach allows more performers to earn a living being creative (and not have to have a day job). Books are not performance art. I don’t necessarily want to hear my favourite author read their work (live or on an audio book), I won’t go on their stadium tour, I may buy the T-shirt (and perhaps that’s where the cover art gets displaced to). Books are also BIG compared to songs, it takes months to write a novel (and many train rides and flights for me to read one).

As the value chain between author and reader gets squeezed we need to find some new local optimum where the author earns enough to keep writing, and the other ancillary people like editors get paid. I notice that whilst many of my favourite authors like Cory Doctorow and Charles Stross are keen to see their work in eBooks, and keen to avoid nasty DRM etc., they also seem go out of their way to support their publishers, editors etc. by not providing a side channel around them (where the fan could go straight to the author and pay them for content in certain forms). This contrasts with the possibilities that digital distribution opens up, which I experienced first hand when Craig Murray took the decision to self publish The Catholic Orangemen of Togo (having been threatened with litigation under the UK’s rather onerous libel laws). Having ordered a hardcover from Amazon that clearly wasn’t going to get to me any time soon I ended up cancelling my slice of dead tree and sending Craig what he said he’d get from the cover price (if I bought direct) and printed the PDF to read on the train. The economics of this transaction are interesting – cover price £17.99 (discounted to £11.87 on Amazon), profit to Craig £3.60 (only £0.80 from Amazon), cost for me to print 226 page PDF on my duplex laser printer £1.13. So…

- Craig doing his own distribution gets him £3.60/£17.99, or around 20% – and £14.39 is left on the table for ‘distribution’

- Me printing Craig’s PDF gets him £3.60/£4.73, or around 76% – with nothing left on the table for ‘distribution’

- Of course if abuse DRM hadn’t put me off buying an eBook reader then I wouldn’t have needed to do any printing at all

- Amazon selling Craig’s book gets him £0.80/£11.87 – just 7% – and £11.07 goes into ‘distribution’

Obviously Amazon is much better at ‘distribution’ than Craig is, but more obviously self publishing eBooks could totally ruin the ‘distribution’ business. No wonder Amazon is being heavy handed, but I sense that there’s more at stake here in the long run, and that the time dimension of how we consume from established authors is just the tip of a very large iceberg.

Updated to add and moments after I pressed publish another great piece of commentary from Charles Stross. I think we can agree on the end game ‘the correct model for selling ebooks (profitably and at a fair price) is to establish a direct-to-public retail channel, like Baen’s Webscription subsidiary. Oh, and once you’re there, you can ditch the annoying DRM.’ All I’m left wondering is how much of a role publishers will have in that direct-to-public channel, especially for new authors?

Filed under: marketing | 1 Comment

Tags: books, ebook, economics

With the launch of the iPad now a few days behind us, and the dust beginning to settle I thought it was time to reflect on what this is going to mean to the marketplace.

Firstly this is a device for ‘normals‘ (though I do like the term ‘muggles‘). It is intended for the consumption of media, not its creation. It was not really made for the geeks that have spent months drooling over what it might be. Many of those geeks will buy it anyway, but I suspect that there will be a hefty side order of remorse with many of those purchases.

Firstly this is the end of the beginning. Tablets have been around for a while now (and I really liked my X60T) but Apple has shown the world how to do this stuff properly. Prediction 1 – by the end of 2010 the market will be flooded with copycat devices, most of which will run Android.

Secondly, the convergence of netbooks and tablets is starting to happen. One of the CES launches that I missed at the time was the Lenovo s10-3t. It lacks the HD screen and built in 3G that I’ve been hoping for, but I may just have to get one anyway (particularly as fan noise from my S10e is starting to drive me mad). Prediction 2 – the needs of ‘creative’ users will be served by similar form factor devices that run ‘desktop’ type operating systems like Windows 7 and Chrome.

It’s worth taking a look at the media that underpins the consumption experience on these devices (and think about their relationship with sales portals like iTunes):

- Music – I’ve had an iPod since before iTunes came to the PC, which was well before the store came along. I’ve never much liked the iTunes model, which is why the only thing I’ve ever bought there was RATM last Christmas (and I didn’t actually listen to that track). There is now plenty of choice around where to get legal mp3s from, and services like TuneChecker that will find you the cheapest source for what you want. Those that find a close coupling between the iTunes store and music on iPods/Phones/Pads really put the mug into muggle.

- Video – I use my iPod touch a fair bit for video (and used it a lot more before getting a netbook, though these days it’s been relegated to the backup device when the netbook battery can’t hold up). I don’t use iTunes for video either – there are plenty of tools out there that will create me a suitable mp4 file from whatever the source happens to be. Clearly there can be copyright issues going down that track, and I’ve moaned before that the market isn’t really satisfying it users, but I won’t hold my breath for a pragmatic solution.

- Books – this seems to be where all the action is right now, with a fierce battle brewing between Apple and Amazon. I’ve yet to see any meaningful detail about the iBook application, its relationship to the iTunes store, and just how horrible the DRM will be; but I’d be amazed if it’s not horrible. Of course Amazon already have a Kindle app for the iPod/Phone, so surely users can choose between two different types of abusive DRM (provided that Apple don’t use the AppStore approvals process to edge Amazon out). Of course when the various flavours of AndroidPad come along they too will probably get a Kindle App. Part of me wonders whether Kindle (the service rather than the device) will become sufficiently ubiquitous that people will ignore its limitations, but I think that the more open tablets that will follow the iPad into the market will create a demand vacuum for open eBooks. Predicition 3 – if Amazon or Apple can find a way to do DRM free eBooks, where they preserve the rights of the buyer more strongly than the rights of the ‘content owner’ (aka content distributor) then they will clean up, otherwise they’ll be leaving a gap in the market for a new player (and let’s not forget Google here).

- Something else worth dwelling on here is that the iPad isn’t a direct competitor for an eBook reader like the Kindle. There are compromises each way in terms of display quality, battery life and flexibility. I’m still not entirely sure whether I’d like (and be willing to sacrifice the space an weight to) another device just for eBooks, but it’s a largely academic question until somebody starts selling eBooks that I’m willing to buy

- Games – people will want to run games on these things. Popular stuff will be ported across platforms. Gaming won’t be a major factor in product or service choice.

- Web – the iPhone revolutionised browsing on the move, and web access will remain an important piece of the tablet experience. All devices will end up with a good enough browser, and people are going to have to think a bit harder about the bits where we do text input (URLs, search boxes, forms) to better suit those with no keyboard.

Commercially I think the iPad will be a success, following the usual Apple formula – by being a premium price high margin product for people that care a lot about design and an integrated end to end user experience. I don’t think that this will be a slam dunk for Apple though (in the same way that the iPhone has been). The iPad will succeed in the same way as something like the MacBookPro rather than the iPhone.

Filed under: Uncategorized | 6 Comments

GDrive

I’ve been a keen user of Gmail since its earliest days, and I also use Google Apps at work, so I’m not surprised by the excitement around the launch of what people are calling ‘GDrive’, which is actually just a new feature of Google Docs that allows arbitrary files to be shared.

What is a little disappointing is the 250MB file limit. Cory Doctorow speculates that this is ‘more to do with keeping the MPAA happy than any kind of technical limitation'[1]. Whilst 250MB is loads more than most of the file sharing services allow, it’s still a painful limitation. One of the challenges I face each year is sharing video of my kids doing their nativity plays etc. with far flung family members. This year I ended up with three files – 200MB, 243MB and 360MB (oops – that’s blown it). In the past I’ve used BitTorrent to share such files, but it’s no fun getting elderly internet civilians using things like Azureus (a client I gave up long ago in favour of uTorrent, which sadly lacks the built in tracker functionality that’s key to this use case).

This year things were much easier, as I used SMEstorage, which is a cloud storage overlay service. The first two files went up with no problems at all, and I think the various grandparents were much happier when they got a simple email with a URL. The third file gave me a bit more trouble, but the outcome was a really cool new feature…

SMEstorage lets you use many of the cloud storage providers as a back end, but comes with some of its own storage so that you can get going (I think this is hosted on Amazon S3). It turns out that I’d blown right past my quota of 250MB with the first two files, but it’s great that they’d let me overcommit by ~190MB without complaining. Initially I put the last file onto S3 (luckily I already had an AWS account), but I was keen to see if there was a better way of using the free storage services. What the SMEstorage guys then came up with was a chunking mechanism, so that a file can be divided up into small enough pieces so that the back end doesn’t complain. With the launch of their revamped site happening today I’m led to believe that chunking will be available to everyone.

There’s lots of talk about how much cloud storage costs, and most services offer some initial capacity free, but here’s one idea:

- Google Apps standard edition with a domain registration costs $10/yr.

- Standard edition allows up to 50 accounts to be created.

- Each account comes with 7GB of storage for email, which SMEstorage can use (in 10MB chunks).

That’s 350GB for $10/yr, which is 63x cheaper than S3 (before we start counting transfer fees). Also I’m not counting the 50x 1GB that the new Google Docs feature would give, so that should really be 400GB for $10/yr, which would cost $720 on S3.

Maybe Google will close the door on this if it gets too popular, but I would speculate that by then the marginal cost of cloud storage will be low enough for few to care.

[1] It astonishes me that the media distribution industry continues to fail to grasp that making life inconvenient for the masses has no impact on ‘piracy’. Whilst this measure may be pretty effective at stopping somebody less technical from sharing their kid’s nativity play it fails to appreciate the asymmetries involved. It only takes one technically savvy person to work around this limit and share Avatar (or whatever is flavour of the month).

Filed under: cloud | 2 Comments

Tags: aws, bittorrent, cloud, gapps, gmail, google, s3, SMEstorage, storage

Getting out of the weeds

After some reflection on my recent series of posts about Paremus ServiceFabric on EC2 I realise that I never provided a high level commentary on what each of the moving parts does, and why they’re important.

- Paremus ServiceFabric – this is a distributed OSGi runtime framework. The point is that you can package an application as a set of OSGi bundles, and deploy them onto the fabric without having to care too much about underlying resources – that’s what the fabric management is there to take care of. What’s especially neat about the Paremus implementation of this is that the fabric management itself runs on the fabric, so it gets to benefit from the inherent scalability and robustness that’s there (and avoids some of the nasty single points of failure that exist in many other architectures).

- OSGi is a good thing, because it provides a far more dynamic deployment mechanism for applications (making it easier to design for maintenance).

- ServiceFabric also makes use of Service Component Architecture (SCA), which allows better abstraction of components from underlying implementation details. This allows parts of the overall architecture to be swapped out without having to reach in an change everything. Jean-Jacques Dubray from SAP provides an excellent explanation of how this improves upon older approaches on his blog.

- CohesiveFT Elastic Server on Demand – this is a factory for virtual appliances. I used it to build the Amazon Machine Images (AMIs) that I needed. A bit like OSGi it uses a concept of bundles, and for some of the software that wasn’t already there in the factory (e.g. the Paremus stuff) I had to create my own. Once I had the bundles that I needed I was then able to choose an OS, and build a server to my recipe (aka a ‘bill of materials’). The factory would send me an email once a server was ready (and optionally deploy and start it for me straight away).

- CohesiveFT VPNcubed – this was the overlay network that ensured that I had consistent network services (that supported multicast) covering the private and public pieces of the project. It basically consists of two parts:

- A manager – which can exist in the private network or the cloud (or both). For simplicity I went with a pre packed AMI hosted on EC2

- A set of clients. These are basic OpenVPN clients. For my AMIs I used a pre packed bundle. For the machines on my home network I just downloaded the latest version of OpenVPN. The manager provides ‘client packs’ containing certificates and configuration files, which need a little customisation to specify the manager location.

- CohesiveFT ContextCubed – this provides the ability to start and customise a bunch of virtual appliances (AMIs) automatically. With the help of their CTO, Pat Kerpan, I was working with a pre release of this service (hence no link). ContextCubed (which I accidentally called ConfigCubed in my post about it) provides an init.d style mechanism that sits outside of the virtual machine itself. I used it to download and install VPNcubed client packs, start the VPN, stop some services I didn’t want, reconfigure the firewall to allow multicast, and add binding config to the Paremus Atlas service (before starting it up). I could have also used it to create hosts files to work around some of the naming issues I encountered, but I think I’ll wait for Pat to fix things up with DNScubed or whatever he ends up calling it. Hopefully in due course the *cubed services will all find their way onto the same virtual appliance, so there can be a one stop shop for stuff that makes an application work in a hybrid cloud (or whatever suits your taste from private to public).

One thing that would have been fun to try (but that I didn’t attempt) is closing the loop between the PaaS management layer in ServiceFabric, and the IaaS management layer in ContextCubed. This would allow (for instance) extra machines to be deployed dynamically to satisfy peaky workloads (or deal with failure) running on ServiceFabric. I’ll leave that for another day.

Filed under: cloud | 3 Comments

Tags: aws, cohesiveft, ec2, elastic server, nimble, osgi, paas, paremus, sca, servicefabric, vpn, vpn cubed

I spent a couple of hours tinkering with this over the holidays, but mostly put it down and got on with eating, drinking and being merry.

The first breakthrough was that ContextCubed just worked once I had the right Ruby Gems installed (and in fact day 5 had got me to within one line of installation). This means that I can now start up a cluster of ServiceFabric Atlas nodes that automagically join the VPNcubed overlay network with a single command line – nice :)

The final hurdle turned out to be a mix of name resolution and binding. The former issue I fudged with some hosts entries, and the later was a simple one liner in the Atlas config.ini (which is trivial to automate with ContextCubed). Once ContextCubed gets its DNS appendage (DNScubed?) then there should be a decent mechanism for name resolution that ties into the VPN overlay.

When I embarked on this project it was supposed to be simple, and if I look back at all the problems that I encountered and lessons learned then there wasn’t really anything fundamental standing in my way. From a personal perspective the 2-3 man days that I’ve sunk into this have been very useful and educational (and it’s been nice to get my hands dirty with some real techie stuff); and the great thing is that I can now achieve in seconds stuff that was taking me hours when I set out on this journey.

For the sake of completeness here are links to the previous entries (and I know I should have done a better job of chaining them, but I can go back and fix that now). Day: 1, 2-3, 4, 5

If you’ve found this series interesting, then you might also want to take a look at my corp blog post ‘Designed for cloud‘. PaaS in general, and ServiceFabric in particular (with its ability to handle OSGi at scale), are just the sort of thing that software developers need to help them move from design for purpose/manufacture to design for maintenance.

Filed under: cloud | 1 Comment

Tags: aws, cohesiveft, ec2, elastic server, nimble, osgi, paas, paremus, sca, servicefabric, vpn, vpn cubed

Techlust – Lenovo IdeaPad U1

I almost certainly won’t end up buying one of these, but it has the look of something that I’ve been hoping for since giving up my X60T tablet for my s10e netbook.

I have missed the ability to draw stuff on the screen. That gap has kind of been filled now as Santa brought me a Wacom Bamboo Pen tablet for Christmas, which is absolutely wonderful for photo editing and such. It would just be brilliant though if that was built into the screen rather than another piece of kit to carry around (and if the screen was sufficiently high resolution to make a decent ebook reader). The Bamboo does almost look like it was made for my black s10e though, as they have very similar aesthetics, and go together very well size wise.

I suspect that the U1 will be cursed by lots of first of type fatal flaws, but hope that by the time CES rolls around next year there will be some decent options in this area. Meanwhile I’m on the lookout for a Pine Trail netbook with a 1280×720 screen and integrated 3G, and if one comes along with a touch screen then that would be awesome.

Filed under: technology | Leave a Comment

Tags: netbook, tablet

Between snow, getting some prerequisite scripts and docs a bit too late and various other stuff getting in the way, there hasn’t been too much progress today. I think I have everything set up to launch a complete cluster of Atlas agents in the sky, and get them to attach to the overlay VPN and call home, but the mechanics aren’t quite working yet (I’m drowning in Ruby dependency issues).

Today was supposed to be my last working day of the year (though I’ll be in the office on Monday for a client meeting that couldn’t be moved), so this saga will draw to a halt for the time being. I may get some time to hack away over Christmas, but no promises.

Two small victories:

- I figured out the command line I need to kill the SSL Elastic Server manager (which conflicts with Atlas in wanting port 4433):

ps -ef | grep ssl_server | awk ‘{ print $2; }’ | xargs kill -9 - I also figured out why my security groups between vpncubed-client and vpncubed-mgr weren’t working – I was using public IPs for wget and in vpncubed.conf rather than private IPs – doh!

Hopefully this story will have a quick and happy ending in the New Year.

Previous post – Paremus ServiceFabric on EC2 day 4

Following post – Paremus ServiceFabric on EC2 – declaring victory

Filed under: cloud | Leave a Comment

Tags: aws, cohesiveft, ec2, elastic server, nimble, osgi, paas, paremus, sca, servicefabric, vpn, vpn cubed

The multicast woes are now behind me (thanks Dimitriy), and I now have a fabric that spans my home network and EC2. The problem with multicast turned out to be firewall related, and the simple fix was:

/sbin/iptables -I OUTPUT -o tun0 -j ACCEPT /sbin/iptables -I INPUT -i tun0 -j ACCEPT

Tomorrow I’ll try to get something running on the fabric, and will also take a look at automating the deployment process for members of the fabric.

Previous post – Paremus ServiceFabric on EC2 days 2/3

Following post – Paremus ServiceFabric on EC2 day 5

Filed under: cloud | 1 Comment

Tags: aws, cohesiveft, ec2, elastic server, nimble, osgi, paas, paremus, sca, servicefabric, vpn, vpn cubed